Symbolism for Beginners

For tens of thousands of years, wild horses have inspired humans—to nurture, to create, to slaughter—culminating in the past century of America’s legal and psychological battles over the horses we can’t own.

For a few months a few years ago the wallpaper on my computer desktop was a photograph of a band of wild horses galloping over a flat, marshy landscape of water and earth tones. It is an aerial shot taken from some distance. There are 16 horses in the frame and they span, generally speaking, the middle third of the image. If a compass and the photograph were synched, the horses would be running east, and since this is a photograph of a band of wild horses in south central Florida, that would mean toward the Atlantic. Even though the herd does not register as much more than specks in the scene, these specks still communicate speed and animal physicality. I was living in New York City at that time and the image struck some chord inside me about the world beyond the Bronx. Plus, I’d always loved horses, even though it had been years since I’d spent any real time with them. It was a sentimental nod to the schoolgirl I used to be.

That schoolgirl: a little plump, quick to laugh, fond of the family dog she walked around the block while reading a book. Those books, more often than not, were horse books: good ones and bad ones; classics as well as bald attempts to capitalize on the young girl/horse market that was my general type. Since turning 18 and passing that point by which girls should have replaced their horses with boyfriends, I have often wished there were more horse books for adults that weren’t awful. Like the photograph on my desktop, this amorphous sense of nostalgia was what found me re-reading Misty of Chincoteague while muddling through the winter doldrums. I was at once astonished and embarrassed that when that last paragraph arrived, I was weeping. “I re-read Misty,” I told my friends. “It’s lovely. The woman could write.” They would half-smile and nod. Then they’d turn back to their glass of wine, the commercial on the television, the band on stage, the passing land out the window.

Misty of Chincoteague by Marguerite Henry was published in 1947. It was Henry’s second young-adult novel about horses, but her first bestseller and the book that would remain her calling card right up to the first line of her New York Times obituary when she died a half century later at the age of 95. Misty was “based on a true story” in that the pony and her young owners really did live on Chincoteague Island in the 1940s. Beyond that, however, the facts are few and far between; “inspired by a true story” would be more accurate. The book was published in the midst of a string of classic YA novels that told stories about children and animals. During the Second Industrial Revolution, Americans moved off the farms and into the cities in droves. The agrarian United States was dying. By 1920 as many people lived in cities as in rural areas; by 1930 that ratio had tilted in favor of those in the cities, and the trend has never reversed. The next 30 years were spent responding to that seismic shift. The decades between 1933 and 1963 saw the publications of the vast majority of Henry’s horse oeuvre, as well as other children-animal classics such as The Red Pony, National Velvet, The Yearling, Lassie Come Home, My Friend Flicka, The Black Stallion books, Charlotte’s Web, Old Yeller, The Incredible Journey, and Never Cry Wolf.

Misty is not really about Misty. Mostly it is about growing up and the dynamic between the populated Chincoteague Island and its wild neighbor Assateague. The islands are situated off the coast of the peninsula that curves around the mainland mid-Atlantic to form the Chincoteague Bay. A slim channel separates these two spits of sandy land, with Assateague on the outside shielding Chincoteague from direct hits by the Atlantic. As much as Misty is about horses at all it is about Misty’s mother, the Phantom, who runs with an Assateague herd claimed by a stallion called the Pied Piper. Chincoteaguers have held annual roundups of the ponies since 1835. The Phantom had evaded capture for years, earning herself her name and a reputation. Like many of the Assateague ponies, she was a piebald, meaning her markings were large and spotted. In the novel, however, she is not just any old piebald: the Phantom stands apart from the rest of the wild ponies because of “a strange white marking that began at her withers and spread out like a white map of the United States.”

In January 1912, New Mexico threw its lot in with the country surrounding it on three sides, and in February Arizona followed suit, filling in the final piece of the puzzle to complete the continental United States. In March, Velma Bronn was born on a ranch near Reno, Nev.

The mare’s milk saved Bronn’s father, who, when he grew up and had children of his own, told his daughter that they were both given life by the milk of a mustang.

Two stories from Bronn’s formative years figure prominently in shaping what would become her campaign to save the country’s wild horses. The first is the story of how her grandparents traveled to California in a covered wagon with an infant—Bronn’s father. Her grandmother’s milk dried up about halfway through the journey. Fortunately, a mustang mare her grandfather had tamed to pull the wagon had recently given birth to a foal of her own. It was the mare’s milk that saved Bronn’s father, who, when he grew up and had children of his own, told his daughter that they were both given life by the milk of a mustang.

The second story that looms large is her time spent in a San Francisco children’s polio ward in a cast that encased her entire body from waist to head, at the top of which there was a small hole cut just large enough to slip in a knitting needle to scratch the area within reach of its point. When, after months, the cast was removed, 11-year-old Bronn was able to walk more easily, but her face had been irrevocably deformed. More than questions of beauty or vanity, though, what Bronn seemed to believe in retrospect was that it was her time spent enclosed inside a cast that taught her about captivity.

Having mastered the art of claiming in the 19th century, America had a crash course in the art of losing in the first half of the 20th century, which in turn prompted interest in the art of saving. Niagara Falls, the country’s flagship destination of natural beauty, had long since been surrendered to the hucksters. In 1890, the superintendent of the Census announced there was no clear line of advancing settlement; the American frontier had reached its limit. By 1900, only a few dozen American bison remained of the millions that had once famously roamed the Great Plains. Those that remained lived within the protected confines of the 28-year-old Yellowstone National Park, established based on the collective growing sense that industrialization was threatening that which made America not just beautiful but exceptional: wilderness. Twenty-eight more national parks would be established by 1950. Martha, the last of the passenger pigeons, died at the Cincinnati Zoo in 1914. Americans were beginning to understand they had the power to make disappear, that the places to move to and deplete were dwindling.

Echoing the history of the bison, best guesses placed the number of wild horses roaming western public lands during the 1950s at around 25,000—down from millions in the late 1800s. It follows that Silent Spring was waiting in the wings.

Misty of Chincoteague focuses on two children, Paul and Maureen Beebe, whose parents are off on a mission in China and have left the kids with their grandparents. Paul and Maureen become fixated on the Phantom, determined to capture her and make her their own on the next Pony Penning Day. Their grandfather initially plays the skeptic. “The Phantom don’t wear that white map on her withers for nothing,” he says at one point. “It stands for Liberty, and ain’t no human being going to take her liberty away from her.”

Paul and Maureen are not fazed. They take odd jobs and ferret away the quarters, dimes, and dollars necessary to purchase the Phantom. When Pony Penning Day arrives, Paul is invited to ride with the men in the Assateague roundup. As the riders isolate a herd near the beach, one pony breaks away, and the ringleader sends Paul to chase it down: The Phantom! Slowed down by a newborn foal. As Paul pursues Phantom and foal through the woods, there are moments when he cannot tell foal from fog in the underbrush. He starts to call her Misty. Like her mother, “she, too, wore a white map of the United States on her withers, but the outlines were softer and blended into the gold of her body.”

Standing on the beach before driving The Phantom and Misty across the water to Chincoteague and its waiting fences, Paul has a moment of hesitation. “There was no wild sweep to her mane and her tail now. The free wild thing was caught like a butterfly in a net.” The boy is wise. He knows his horse. At the end of the book, the call of the wild is too strong and the Phantom goes galloping back into the ocean towards Assateague while Misty stays behind with the children, adorable and docile. Metaphors loom large. Call it symbolism for beginners.

The story that shaped Velma Bronn Johnston’s adult life is famous: She, now married and a lowly Reno secretary, was driving to work one morning in 1950 when she found herself behind a trailer dripping blood onto the highway. Each time the driver accelerated, Newton’s laws of motion would disrupt the rate at which the trailer leaked its contents, and the dripping blood would become a full-blown stream. Looking more closely, Bronn saw the blood was coming from a colt and that the trailer was full of mustangs packed like sardines. She almost threw up. Instead, she followed the trailer to a slaughtering plant, where she watched as the horses were dragged to meet their fate. Then, she pulled out the camera that had been fortuitously sitting beside her on the front seat and started taking pictures. And that, children, is how Wild Horse Annie was born.

For as long as humans and horses have coexisted, humans have looked at horses and seen in them that ineffable quality we associate with the things we have lumped into a broad box labeled “Beautiful Things,” along with mountain ranges, the night sky, flowers in bloom, and the female form. The human-horse relationship is so much more intimate than the human-cow or human-chicken or human-sheep relationship. These are animals we ride, and when riding them we have been both mistaken for and mythologized as one and the same being. I don’t need to belabor how little man might have accomplished and how much more slowly he would have done it without the horse. The way we feel about the horse is more like how we feel about dogs than how we feel about stock animals.

For as long as humans and horses have coexisted, humans have looked at horses and seen in them that ineffable quality we associate with the things we label “Beautiful Things.”

Yet as urban dog and cat ownership skyrocketed in the United States between 1920 and 1940, so did meat-processing plants supplying demand for pet food with horsemeat. About 200 such meat plants opened during those decades, even as horses were publicly beloved on a scale we can hardly imagine from today’s perspective. There were the YA novels, yes. There was also Seabiscuit running across headlines and between 1930 and 1948, Gallant Fox, Omaha, War Admiral, Whirlaway, Count Fleet, Assault, and Citation won the Triple Crown in an impressive string, a feat only one American Thoroughbred had managed before. Only four have managed it since; the last one, Affirmed, was in 1978.

There were the westerns, too: Cowboys and Indians galloped out the music of masculinity in books and on screens for rapt audiences of little boys and girls, confirming as fact what the children already felt—that horses were the heroes, and if not the heroes then the heroes’ better halves. And then there was the automobile, altering roads and roadsides alike, letting us drive through national parks without ever setting hoof or foot in them. Domesticity was on the rise in America but the reverse was true in our dreams where the grass grew always greener, the land was empty and open, and the steeds were swift enough to outrun any enemy, real or imagined.

Wild Horse Annie was a westerner, a rancher, and a conservative. It was never her intention to advocate that horses run free forever, unchecked and unmanaged. Her concern was that wild horses not disappear entirely (as she believed they were in danger of doing), and she even foresaw a time when the population would rebound in such a way that round-ups and humane disposal would again be necessary to protect grazing public lands for cattle and sheep. She was inspired by what now read as Tea Party-esque visions of the founding fathers, invoking Jefferson and the Declaration of Independence for her cause and taking the language of the Constitution in writing the bill, her first, that would outlaw hunting wild horses and burros by air and prevent the polluting of water holes in Nevada. “We, the people…” the bill began.

Writing to a legislator about potential roadblocks to the mustang bill, she put it this way: “It is quite apparent that because of the increasing tendency toward the monopolistic use and abuse of our public lands to the exclusion of all forms of animal life not commercially profitable to private interests, and because commercial exploitation of the mustangs and burros for pet food has provided such an expedient means of range clearance, both from a user and management standpoint, we must expect strong opposition to any plan that will interfere with this convenient arrangement.” This curtailment of free enterprise may be where the far left and the far right meet one another, on the far end of the sphere where grander visions of American exceptionalism meet communalism.

Bronn’s tactics were grassroots. Letters from constituents were crucial to the passage of the 1971 Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act. Congress received more letters from the public during the late fifties through the 1960s about saving the wild horses than it did on any other subject save Vietnam. The vast majority came from American schoolchildren whose teachers saw the debate as an opportunity to teach young people the basics of civics and democracy. It became known as the “Pencil War,” and the students, Bronn’s “Children’s Army.” The children were asking their representatives to save an animal that represented a world in whose shadow they were living but which they would never actually know. What they knew of it, if it had ever existed to begin with, they knew from screens and books, books and screens. The title of Bronn’s favorite public talk was “The Fight to Save a Memory.”

When I was little, sitting in the backseat on long car trips with my family, I’d spend the miles galloping my fore- and middle fingers in place as the scenery passed abstractly at 65 miles an hour. These two fingers mimicked the front two legs of a horse. Sometimes my thumb would play the part of the animal’s hind, the top of my hand, the animal’s back, while the rest of the horse—head, neck, mane, tail—was so fully imagined as to be almost visible to an adult in the front seat.

My tiny phalangeal equine could run all out for hours. It could jump, in stride, signs for gas and fast food, telephone poles, exits to nowheresvilles, the latest numbers in the mileage countdown to Portland, Maine; St. Louis, Mo.; or home, Charlottesville, Va. When the windows were up, the horses that lived in my hands raced the car on the windowsill in an endless dead heat. When the windows were down and my arm in the open air, the horses that lived in my hands would go wild, galloping alongside us in the grass beside the highway, the way wild horses, according to picture books and movies, sometimes did with trains rattling west across the dry grasses of the Plains. I outgrew the windowsill races, but sometimes even now, when the window is down, for old time’s sake and out of habit, I’ll find my forearm out the window, letting loose a wild horse.

The fourth sentence of Part Two of Misty reads, “The heavy beach sand seemed to pull them back, as if it felt that human beings had no right to be there.” If the definition of wilderness is land without evidence of human hand, then wilderness has not existed in North America for thousands of years. We have inhabited the natural world since Eden. Over the centuries our relationship to so-called wilderness has served as a barometer for our inner reserves of spirituality, fear, idealism, and romance. This trouble with wilderness is at the root of semantic arguments about whether horses that roam free on public lands are wild or feral, mustangs or broomtails.

Assateague wasn’t always an unpopulated island of wild ponies. Settlers had lived there since the 17th century and been rounding up the horses, claiming the ones they wanted for their own since the 19th. This changed when much of Assateague was bought by a rich man who forced those living on the island to pack up and move across the channel to Chincoteague, where they remained.

I’ve never seen a live mustang on the range, but a photographer I follow on Instagram has lately focused his lens on horses living on Nevada public lands. Every few days he posts another black and white shot of a scraggly group of horses with visible ribs against a backdrop of sagebrush, cacti, and mountains like sand castles. Sometimes the horses are close enough for him to have touched them, had he wanted to. I find myself wondering whether these images are just another iteration of ruin porn.

The wild horses I’ve seen myself have born some resemblance to this: They are only nominally wild.

The wild horses I’ve seen myself have born some resemblance to this: They are only nominally wild. When I stood on a wooden platform overlooking a marsh in January, four Assateague ponies didn’t bat an eye as I snapped away with my camera. In summer, the Park Service has had trouble keeping ponies, begging for food, out of the road and away from tourists’ cars. Last spring, on Cumberland Island off the coast of south Georgia, which has its own small collection of ponies running around, I stepped to the side of the path as a skinny bay plodded past. My thought then was how strange the pony looked on its own without a herd, headed wherever.

Marguerite Henry published a YA biography of Wild Horse Annie called Mustang, Wild Spirit of the West, in 1966, 19 years after the success of Misty, and one of the last in her series of equine biographies. Of all her novels, Misty and Mustang are Henry’s most overtly patriotic. Strangely, the surname Beebe appears conspicuously in both books. In Misty, Beebe is Paul and Maureen’s last name. Their grandfather is Grandpa Beebe. In Mustang, a journalist named Lucius Beebe (no apparent relation to Paul and Maureen) who writes for The Enterprise in Virginia City, Nev., is among the first members of the press corps to hoist the flag for the wild horse as an American icon to be protected and preserved like Yorktown or Monticello and to publicly advocate for a bill outlawing mustanging, or the hunting of wild horses, mostly for pet food. While maps of the country might have sat on the withers of The Phantom and Misty, Lucius Beebe sat at a desk once used by Mark Twain. This is true.

Beebe, a New Yorker, had moved to Nevada, bought the then-defunct Enterprise, revived it, and eventually saw it become—for a time—the most popular weekly around. The desk at which he wrote editorials was the same one at which Samuel Clemens first signed his work “Mark Twain.” Those editorials were part of a called column called “This Was the West” that Beebe co-wrote with his lover, Charles Clegg. The men may have had their own thoughts about freedom and what it looks like.

The line that separates easterners from westerners is as hard and fast as the Mason-Dixon. Different sides of these lines breed different sorts of people. So says regionalism, and there’s some truth to broad strokes. Nature- and freedom-loving westerners do not trust those uptight, bureaucratic, urban easterners. But not all of the east is “East Coast,” even on the coast. The 23-mile tag team of bridge and tunnel that spans from Virginia Beach across the Chesapeake Bay to the Eastern Shore is as much a display of outwitting Mother Nature as the Transcontinental Railroad is, and it is not a point of access for the phobic. Its asphalt is littered with the carcasses of gulls. If one were to glance down from above, the bridge would appear nothing as more than a stray hair on an enormous sheet of paper. The northbound lane opened in 1964 but the southbound not until 1999. What I’m saying is that the Eastern Shore is remote, and its people are less easterners than islanders. On Pony Penning Day in Chincoteague, there are lassos and cowboy hats and yeehaws. These have no doubt been part of the show since the story of Henry’s novel jumped its pages and become the island’s economy, but the theatrics are also perhaps part of an ethos adopted by people who are as familiar with landscapes of loneliness and hardship as any Nevada rancher.

In Greek mythology Poseidon is the god of oceans, storms, and horses. He is mercurial and powerful. In The Odyssey, he is even more powerful than Zeus and Odysseus’s greatest foe. When Odysseus at last holds Penelope in his arms, he describes the feeling as “longed for as the sun-warmed earth is longed for by a swimmer spent in rough water where his ship went down under Poseidon’s blows, gale winds and tons of sea.” Poseidon has the power to both calm waters and wreck ships, so, to appease him before setting sail, sailors would sometimes throw horses overboard as a sacrificial offering. In other stories, Poseidon created horses to impress Demeter, after she challenged him to imagine the most beautiful animal in the world.

People who love wild horses like to tell romantic stories about their exotic origins and their original Ice Age habitats. Others opt for the more prosaic explanation that the horses are simply the descendants of workaday nags settlers brought with them, let loose, and never reclaimed. The more fanciful explanations of island ponies often involve Shakespearean shipwrecks within sight of land from which a few scrappy equine survivors swam ashore to freedom and happily ever after. That’s the version Henry chose for the Assateague ponies: The first two chapters of Misty, which serve as a preface, recount the fictional events of a Spanish galleon manned by a cruel captain who is transporting a herd of ponies to Peru to work in the mines. When a storm hits, the sole stallion’s flight response kicks in and spreads through the mares: “Nineteen pairs of brown eyes whited. Nineteen young mares caught his anxiety. They, too, tried to escape, rearing and plunging, rearing and plunging.” The dark hull, the confinement, the fear, the desperate efforts at freedom. It’s difficult now not to replace the equine eyes with human ones, the ship’s Spanish origin with an African one. This makes the last line of that first chapter all the more striking. “They were far from the mines of Peru,” it reads. It’s as if Henry is offering up these ponies as an alternate reality, an alternate history of what happened once we crossed the ocean and touched this unknown world. You could read the passage as a re-visioning of the conquest story, as a re-visioning that begins with the heros’ freedom, not their captivity.

It is the geometry of no hills, the topography of emptiness, of a hitch-hiker thumbing north whose face makes you shudder with unpleasant premonitions as you pass.

Chincoteague and Assateague sit at the northern tip of the Delmarva Penninsula, near a road that begins in Virginia and crosses the bay, embarking on its straight shot up and across state lines, providing a firm y-axis for the sharp equations of these environs. There aren’t many people around. This is the rural geometry of cotton fields. It is the geometry of abandoned tobacco lots left loitering by the sides of roads. It is the geometry of power lines, roadside fireworks, pine trees, for sale signs, outdated billboards, and abandoned buildings with “BUFFET” spelled out in all caps across their side walls. It is the geometry of no hills, the topography of emptiness, of tried-and-failed, of a hitch-hiker thumbing north whose face makes you shudder with unpleasant premonitions as you pass, the wind from your car lifting the strap of his knapsack so that it flaps for a moment in the direction of your taillights like a hand waving goodbye to a hunched back. The land looks like it might blow away in a strong breeze. Come hurricanes, it has.

The landscapes of the Eastern Shore and the deserts of Nevada are not dissimilar: neither are pastures of plenty. Both are beautiful in a spare, empty way. But again, it is not the beauty of bounty. Neither give freely of themselves or even have much to give in the way of human or animal survival. Their beauty lives in tension with hardship. But in either case—shore or desert—if you insert a herd of wild horses in the frame, the image changes. What was (and is) a landscape of loneliness is transformed as if by sleight of hand into a landscape of freedom. What was empty becomes full with the promise that there is something out there, perhaps more precisely, something out there for us, and that is a heavy awareness. In dreams begin responsibilities.

For a long time I thought the cave paintings of horses in Lascaux and Chauvet, France, were small, renderings of animals in miniature. It was only recently that I realized the paintings are enormous, that giant horses cover the granite walls and ceilings like tapestries and loom over the tourists like visitors from the dream worlds that were the first forays into our own imaginations.

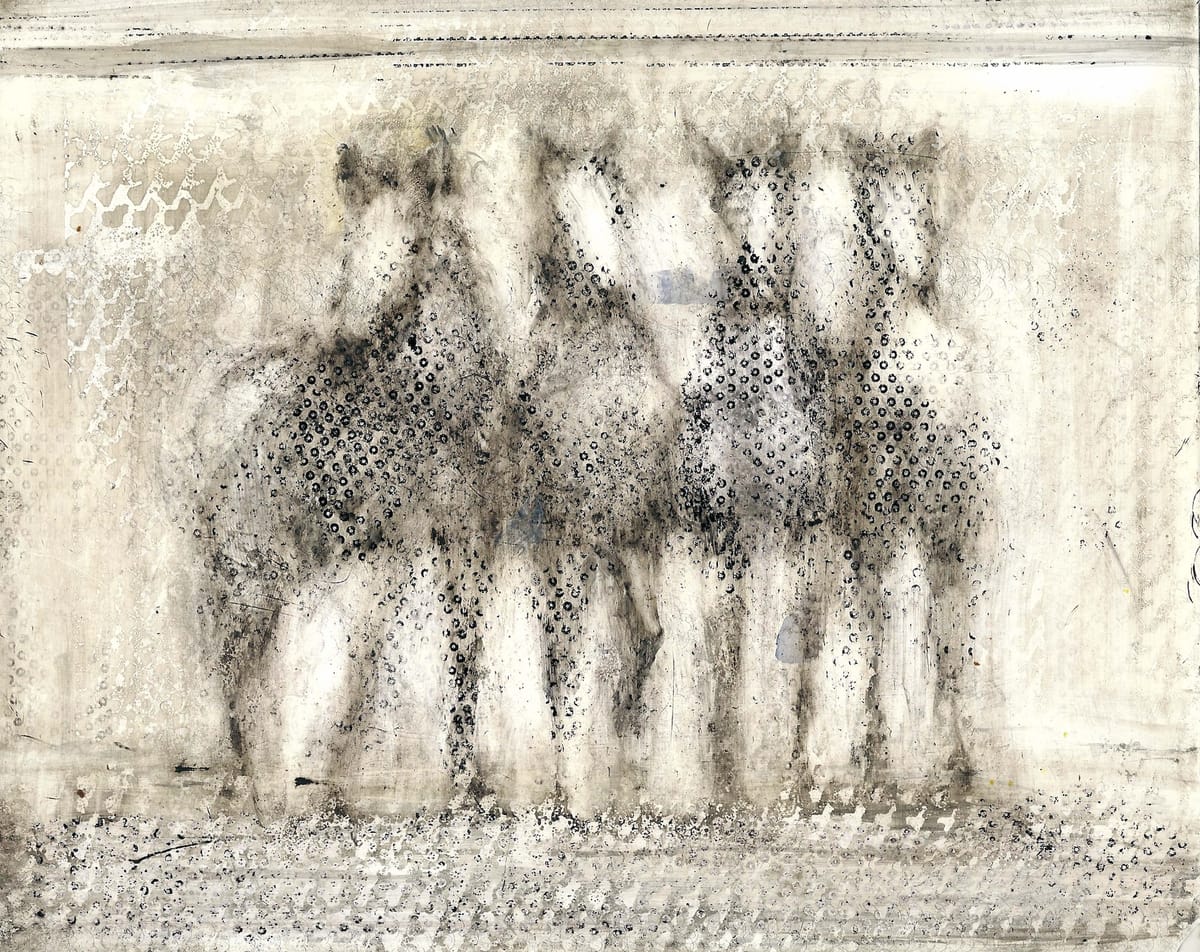

The third chapter of Misty and the first chapter of Mustang both include scenes of the child protagonists entranced at the sight of a herd of wild horses. In Misty, Henry writes, “With manes and tails flying, a band of wild ponies swept into the natural grazing ground. A pinto stallion was in command. He bunched his mares, then tossed his head high, searching the wind.” In Mustang, Henry describes the scene this way: “Far off on the mesa a string of mustangs was running into the wind. It must have been into the wind, for their tails streamed out behind and their manes lifted like licks of flame.” This is not Henry repeating herself. This is the language of looking at wild horses in motion.

My first feeling when looking at a picture of wild horses running across a range or a beach is one of admiration and awe. My second feeling is a comment on my first: embarrassment. The image of the wild horse is as saccharine as it is beautiful. I try to explain to my students the nature of cliché and beg them to do their best to avoid it. I tell them that a cliché is a thought or an image so commonplace it has lost its meaning. I’ve been looking at a lot of pictures of wild horses recently, pictures by accomplished photographers, many vetted by National Geographic editors. A palomino foal looking up at the camera from a behind a field of purple flowers. A herd of bays together in an all-out gallop across a mesa. A black yearling reaching his head around to scratch an itch as a buckskin dozes beside him, their profiles in relief against a bright blue sky. These photographs are beautiful, but are they too close to soft lighting and blurred edges? All I know is that I will probably never hang a picture of a herd of wild horses in my house. I don’t yet understand what part the word “beautiful” plays in my personal history of the English language.

When news broke in March 2014 that scientists had detected gravitational waves that proved a theory of the “bang” in the Big Bang hypothesized in 1981 by Russian-American physicist, Andrei Linde, footage of a graduate student giving Linde the news went viral.

“I always live with this feeling: What if I am tricked, what if I believe in this just because it is beautiful?”

In the video, Linde and his wife answer the door. The student says, “I have a surprise for you. It’s five-sigma, r point two.” These are the words Linde had been waiting on for more than 30 years, the perfect equation that proves his hypothesis. Linde steps forward. His expression moves from irritation to disbelief to deep thought to joy in the span of three seconds. He has white hair and crow’s feet. He asks the student to say it again.

Cut to: champagne, clinking glasses, marveling at numbers you can’t see and, if you could, that you wouldn’t understand.

Cut to: Linde alone, answering questions posed by an off-screen interviewer: “Even if this is true,” he says, “this is a moment of understanding of nature of such a magnitude that it just overwhelms. Let’s just hope it’s not a trick. I always live with this feeling: What if I am tricked, what if I believe in this just because it is beautiful? What if…” He trails off. His next word is simply: “yes.”

Five sigma r point two. What if I believe in this just because it is beautiful?

In a dictionary the words go in this order: sense, sensibility, sensitive, sensualist, sentence, sentient, sentiment, sentimental. It’s a list that forces the reader to confront the fog that envelops the line between thinking and feeling. Sense as in “intuition” or “common”? Sensitive, appropriately or overly? Sentient beings. Sentimental journeys. Sentence: to communicate what? It’s at the root, sent: to feel, sense, perceive. Thought and feeling spring from the same seed even if simple assumptions say that they gravitate toward opposite sides of the tree, the feeling words pulled to the feminine side, which is also the children’s side, the thinking words pulled to the side that belongs to the men and adults. As is the case with many words that have garnered negative connotations over the centuries, “sentimental” was once a compliment meaning “refined and elegant feeling.” It is only gradually and after generations that it became synonymous with “indulgence in superficial emotion.”

But what if those repeated pictures of wild horses running across the range, their manes and tails streaming behind them like flames or wings or flags or dreams, had been cropped? What if you widened the frame and saw an airplane above them or a pickup beside them, chasing them, and from which they were trying to run?

My favorite lullaby has always been “All the Pretty Little Horses.” Hush-a-bye don’t you cry, go to sleep my little baby. When you wake you shall have all the pretty little horses. Blacks and bays, dapples and grays, all the pretty little horses. It is sung slow, sad and mournful, from the perspective of a mother to her child. The origin of the song is not entirely known, but is likely an old slave song. One of the commonly repeated verses goes, Way down yonder, In the meadow, there's a poor lil lambie. The bees and the butterflies, peckin' out its eyes, the poor lil lambie cried, "Mammy!" I have an a capella version sung by the duo Anne and Elizabeth in a minor key. The harmonies are nothing if not beautiful. More than that, horses are what, in dreams, make the hurt go away.

Women and children are the ones who have, historically, wanted to save the wild horses, and these women and children are often a little damaged. In the 1961 movie The Misfits, written by Arthur Miller who was then married to Marilyn Monroe, Monroe’s character has just gotten a divorce. She is sad. She doesn’t trust men anymore, or the way they love women. She meets Clark Gable and with him she is as happy as she can be for a while in a cabin outside of Reno, but then one day he and some friends head up into the mountains to do some mustanging and she comes along, naïve to what “mustanging” means. A battle of the sexes ensues against the backdrop of a wasteland: Monroe begs Gable and his friends to let the mustangs go, as they laugh, and then yell, at her. In the end, there’s enough resolution for the average viewer.

The mens’ reaction to Monroe validates the fear of dismissal and irritation that hangs over any heroine in a horse story. That’s why these books are so rife with tomboys and high-spirited, strong-willed girls. It’s why in Mustang, Bronn’s father warns her not to be girlish: “You can’t just rage and gnash your teeth and cry about wild mustangs kicking up dust in the moonlight. That’s ’zacktly what flyin’ mustangers and the cowmen and sheepmen and all the legal folk are goin’ to expect from a girrrl. What I mean is, you got to shock ’em with facts hard as bullets.”

Like everybody, I’ve got my own scars, but unlike most I’ve sought solace from them on horseback. As a woman who rides horses, I have become reflexively defensive when the what-to-do-with-the-wild-horses question is raised. My hackles go up. I shift my gaze. I equivocate. I have no idea. What the hell do I know.

Only a handful of horses have been stuffed and put on display for the American public on vacation. There’s Gen. Custer’s horse Comanche, which you can go gawk at in Lawrence, Kan. In 2010, Roy Rogers’s taxidermied Trigger, who had been on display in museums in California and Missouri, was temporarily taken off the tourist market when he sold at auction for $266,000. The man who bought him plans to build a western museum with Trigger as the main attraction. Then there’s Stonewall Jackson’s horse Little Sorrel, and Misty, both of them in Virginia, and both of whom I saw when I was a child. I saw Little Sorrel on a second-grade class trip to Lexington, an hour south of Charlottesville. I remember standing in the dark basement of the Virginia Military Institute’s chapel, staring at the horse that was lit like a movie star while looking like the opposite of life, and not finding it at all strange that my school took us on field trips to see the stuffed horses of Confederate generals. My memory of seeing Misty is foggier. I remember being unimpressed by the doublewide that called itself a museum and I think I remember feeling slightly spooked by her glass eyes and dull, dry, faded coat.

When I went this past January to refresh my childhood memories of Chincoteague and Assateague, it was the middle of winter. All the hotels and T-shirt shops and mini-golf courses and summer rental offices that were named, if not for Misty then for the wild ponies collectively, were closed for the season, including the Misty Museum, and I wondered again about the line between gauche commerce and community pride. I had wanted to see that stuffed horse again. I wanted to look at her withers and decide for myself whether or not I saw on them the faint outline of the continental United States, but that verdict will have to wait for a trip some other time.

A memory is a moving picture. Here, mine is of a static strip of land, sandy and dusty. I am looking at the ground. It is passing so rapidly that if the image froze it would be blurry to the point of abstraction: a Rothko of pale yellows, creams, light browns, tempered greens. I am two. In a few years I will have learned the anxiety associated with having no control over my own direction and speed, but for now I trust my mother, who is pedaling the bike, completely, and that fear has not yet been born. The ground is the ground of Assateague, where my family has been camping with another family. The image is no more than a few seconds long and involves nothing else aside from scrappy topsoil passing into the frame and then out of it again, no awareness of behind or ahead, before or after. When the subject comes up, this is the scene I describe and call my first memory: Just land going and going and going and going beneath me.