The Gales of November

On Nov. 28, 1966, the SS Daniel J. Morrell capsized during a storm, taking 28 of its 29 crewmen to the bottom of Lake Huron. The sole survivor of a Great Lakes shipwreck tells his tale.

He was sitting alone in the restaurant off exit 229, just south of Ashtabula, Ohio. It was midafternoon, so the only other diners in the underexposed room were a pair of old men dragging out a long, conspiratorial lunch. He looked younger than I remembered him from our first meeting, during Engineers Day at the Soo Locks, where he’d introduced himself to me as “the only survivor from the Daniel J. Morrell.” A gold stud was stamped into his fleshy earlobe, and his blue eyes—eyes as pale as the shallowest waters—did not look tired enough to have been watching the world for 65 years. They looked like the eyes of the young man who’d been adrift on that life raft for 36 hours, with his shipmates freezing to death beside him. The face was broader, the combed-back hair had thinned and lost its color, but the eyes declared, “I’m still here. I’m still alive.”

Dennis Hale was the last man to board the Morrell for its last run of 1966. Bethlehem Steel had been planning to lay her up at the end of November, but another boat broke down, so the Morrell was ordered to sail from Buffalo to Taconite Harbor, Minn., for one more load of iron ore.

Hale was in his third season as a watchman. He had become a sailor after quitting low-paying jobs as a cook and a restaurant manager, and he loved the card-playing, bar-hopping camaraderie of the sailor’s life. Some sailors complained about the loneliness, but Hale, who’d spent his youth being passed between his aunt and his widowed father, felt he’d found a home. He was closer to his shipmates than he was to his wife and children.

While the Morrell unloaded in Buffalo, Hale got leave to visit his family in Ashtabula, 100 miles away. The boat was unloaded quickly, and Hale made it back to Buffalo just as she was clearing the breakwater. Radioing the captain from a Coast Guard station, he was told to jump on board the next day, at a fuel dock in Windsor, Ontario.

The Morrell left Windsor early on the morning of the 28th, hoping to beat a blizzard that was howling across Michigan at 70 miles an hour. Even the St. Clair River was a hard slog in that weather. November is the most dangerous month on the Great Lakes, as Arctic nor’westers trying to force autumn out of Michigan are resisted by lingering warm, damp air from the Gulf of Mexico. The storm of Nov. 7-10, 1913, remembered as “The Big Blow,” sank a dozen ships and 275 sailors. The Edmund Fitzgerald sank on Nov. 10, 1975, still commemorated as “Fitz Day” in the Upper Peninsula. As Gordon Lightfoot sang in the ballad that made Great Lakes shipwrecks known worldwide, “that good ship and true was a bone to be chewed / When the gales of November came early.” Hale got off watch at 8 a.m. When he reported for his evening shift, eight hours later, he was surprised to see the Morrell had just passed Port Huron.

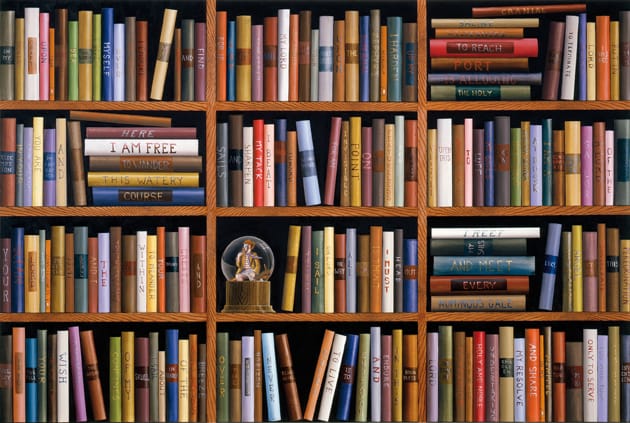

On the open lake, 25-foot waves were shoving the boat from both sides. It was rough, but not too rough for Hale to walk across the open deck to the galley—food is one of the few diversions on a boat—or to lie in his bunk, reading Carl Sandburg’s biography of Lincoln. At 10 o’clock, he set the book on a shelf, and fell asleep as the wave-chopping bow shuddered beneath him.

Two hours later, Hale’s library tumbled to the floor. In the sudden midnight darkness, he heard two loud bangs. Snatching his lifejacket, he rushed out onto the slushy deck, wearing only boxer shorts. The deck was swelling in the middle. A hull girder had given way. Hale had just enough time to race back for his pea coat before clambering onto a raft with a dozen men.

The impact vaulted all of them overboard. When Hale surfaced, he saw a carbide lamp, glowing from the raft. The light flashed in and out of sight as dunes of water gathered up and collapsed. Hale swam toward the shifting beacon, clawing handfuls of wave.

The Morrell was peeling apart. Invisible hands ripped the deck like a sheet of cardboard. The 60-year-old boat ran on coal, so severed steam pipes billowed into the cold air. Sparks crackled from snapped wires. Since the propeller was still churning, the stern didn’t sink, but slid around in a blind half-circle, slamming into the bow, where Hale and his shipmates were waiting for their dangling raft to reach water. The impact vaulted all of them overboard. When Hale surfaced, he saw a carbide lamp, glowing from the raft. The light flashed in and out of sight as dunes of water gathered up and collapsed. Hale swam toward the shifting beacon, clawing handfuls of wave. Two crewmen, Art Stojek and John Cleary, had beaten him there. They pulled him aboard. Soon, they were joined by a fourth, Charles “Fuzzy” Fosbender.

“What are our chances, Denny?” Cleary asked.

“Better than the guys who didn’t make it to this raft.”

Hale settled on his side, with Fosbender’s back tucked into the crook of his legs. The men talked about their children, about going home for Christmas. But they shrieked piteously when waves swamped the boat, followed by autumn-sharpened winds.

At dawn, Hale noticed white foam on Cleary’s lips and poked him, asking “Hey, are you all right?” He didn’t respond. Neither did Stojek.

“John and Art are dead,” Hale told Fosbender.

Fosbender lasted until late that afternoon. By then, the boat had drifted to within 200 yards from the beach, snagging on a sandbar. The raft had oars, but the men were too weak to row.

“Are we any closer to land?” Hale asked.

“Yes,” Fosbender said faintly. He had lifted himself, with one hand on deck and another on Hale’s hip.

“Maybe someone will see us.”

“Well, they better hurry, because my lungs are filling up.”

“Can’t you cough that stuff up?”

Fosbender began hacking. After a few gasps, he announced, “I’m throwing in the sponge” and collapsed across Hale’s hips.

On the afternoon of the 30th, after 34 hours in the water, Hale began to experience visions.

For the next 24 hours, Hale was alone with his dead shipmates. He stuck his fingers in his mouth to stave off frostbite, held his urine to save body heat, and drank by dropping the lanyard of the flare gun into the lake and sucking off the water. Spotting lights on shore, he shouted for help. No one heard him.

On the afternoon of the 30th, after 34 hours in the water, Hale began to experience visions. A white-haired, white-robed man hovered in the air, told him “Stop eating the ice off your pea coat,” and then dissolved.

Then he was in a meadow, where he hugged the mother who’d died after giving birth to him. He walked over a hill, and climbed a ladder, to the deck of the Morrell.

“Dennis, what are you doing here?” the third mate asked him. “It’s not your time yet.”

As Hale was hallucinating, the Coast Guard pulled a body out of the water off Harbor Beach. The man had ice in his hair and wore an orange lifejacket stenciled DANIEL J. MORRELL. In Cleveland, Bethlehem Steel’s fleet dispatcher had already put out an all-points bulletin for the boat. The Coast Guard swarmed over the lake, by air and water. At four o’clock, a helicopter spotted a life raft with four bodies. Hale raised his arm. When they pulled him out, all he could say was “I love ya! I love ya! I love ya!”

When the Morrell sank, Hale weighed 220 pounds. He was rescued at 195. Big galley meals may have saved his life by padding him with insulating fat. He spent the next two weeks in a Harbor Beach, Mich., hospital, protected from reporters who wanted to interview the Morrell’s sole survivor.

He quit sailing after that, went to work as a machinist, and refused to talk about the shipwreck for the next 15 years. He’d been wounded by a newspaper story claiming he’d survived by huddling beneath the corpses of his shipmates. Frostbite took his little toe, and the edge of his foot, but those 34 hours had frozen into his brain a sliver of ice that never melted. Hale was afraid to take a bath after that. He went through four wives. Post-traumatic stress made him restless, but back in 1966, a man didn’t see a psychologist.

In 1981, Hale was invited to Lake Superior State College in Sault Ste. Marie, Mich., for a meeting of the Great Lakes Shipwreck Society. A pair of divers had discovered the Morrell’s bow and were showing a film of their find. Hale hadn’t planned to talk about his ordeal. When he was asked to stand up in front of 500 people, he began speaking hesitantly. Then he saw Father Edward Dowling, the Great Lakes historian. The old priest was in tears. The whole room was moved by this sea story only one man could tell.

“The next morning, I woke up, and I felt better,” Hale said, there in the roadside restaurant. “I just felt really good about myself after doing that. I spoke about it and answered questions, and I found it was good for me.”

“Oh, Dennis Hale,” the men on the boats would say. “I heard that guy survived out there because he was naked.” Which is another half-truth.

Hale became a celebrity in the small world of boat nerds, wreck divers, and sailors. (“Oh, Dennis Hale,” the men on the boats would say. “I heard that guy survived out there because he was naked.” Which is another half-truth.) The week before I met him for lunch, he’d spoken at the Great Lakes Folk Festival in East Lansing. He talked for 30 minutes, then tried to wheedle questions from his abashed listeners.

“I think people are afraid to ask me anything,” he said. “I really appreciate the questions.”

I was afraid to ask him questions. I once worked as a police reporter, interviewing the families of murder victims. But now I was squirming. Hale was so brightly eager to reveal himself; it was like sitting with a man who offers to strip down to his shorts and show off his surgery scars. Everything I’ve written about the Morrell comes from Hale’s self-published book, Sole Survivor. (I also consulted Great Lakes Shipwrecks and Survivors, by William Ratigan.) He had boxes of copies in his house. We drove down there so he could sell me one. As a writer, I’ve never been more grateful for a second-hand tale.

Hale lived a safe 20 miles from Lake Erie. That far from the tight metal belt of docks, lift bridges, and ore-burning foundries, the houses sat on wide, barbered lawns, ruled off from farm sections. Here in the Western Reserve of Ohio, the roads ran toward compass points. Just across the county line, in Pennsylvania, they’d been laid down along creek beds and around hills, an organic disorder that made the map look like a diagram of synapses. Ohio’s geometric layout was a product of Thomas Jefferson’s Enlightenment mind: Ashtabula County had named its seat in his honor.

Hale’s ranch house was a shrine to the sailor’s life. Above the couch was a handcrafted hanging of a lighthouse. There was a misty painting of the Morrell breaking in two, a musty diver’s photo of her bow, and an illustration, titled “Lest We Forget,” of four men lying on a raft.

“I’m there,” Hale said, pointing at a barelegged figure. “I’m the one without any pants on. All I had was a lifejacket.”

He had Gordon Lightfoot’s autograph (they’d met after a concert in Michigan) and Oprah Winfrey’s (he’d appeared on an episode about near-death experiences). He sat me down in a velveteen easy chair and loaded a tape into his VCR: the Today Show, reporting from Whitefish Point, Mich., on Great Lakes shipwrecks. A clip, scarcely longer than a wipe-away, of Hale talking about the Morrell.

“I want to show you one more thing,” he said.

At the bottom of his bedroom closet was a lifejacket, wrapped plastic. He took it out so I could see the stencil: DANIEL J. MORRELL.

“That’s it. It’s priceless. I’ll probably donate it to my wife and kids.”

The home he’d always wanted was at the bottom of Lake Huron. But now he had an identity: “I’m the only lone survivor of a Great Lakes shipwreck.” Forty years later, it was almost a boast. He’d tell you it wasn’t ego, but therapy.

“After I went to the psychologist, I got rid of all the things that were keeping me moving around, keeping me from being at rest.”

Maybe my ears were road-weary, or maybe it was Hale’s eagerness to tell his story, but I got tired of listening before he got tired of talking. As I stood under the carport, my left hand fondling the keys in my pocket, my left foot rocking toward the driveway—Hale lifted the sleeve of his sport shirt, showing off a bicep as pale as a palm. A 40-year-old anchor was fading like an old watercolor. Hale pressed a finger into the blank space beneath, dimpling the flesh.

“I’m thinking of getting another tattoo right here,” he said. “The Chinese character for survivor. That’s who I am, anymore. I thought if I got it in Chinese, I wouldn’t be tooting my own horn.”

Melville wrote that the Great Lakes “have sunk many a midnight ship, with all her shrieking crew.” But there hasn’t been a Great Lakes shipwreck since the Edmund Fitzgerald sank. There may never be another. The decline of the steel industry means fewer ships ply the Lakes. Doppler radar alerts sailors to the violent storms that sank the Morrell and the Fitz. No longer paid tonnage bonuses, captains have no motivation to persist through rough seas, risking the lives of their crews. The Morrell was the next-to-last boat to go down. Instead of a song, she has only a survivor to sing the tale.