The List Maker

Some people keep notebooks. Others keep lists. One type wants to remember; the other wants to forget. What’s not clear is who’s happier for all the scribbling. Confessions of a list-aholic.

Since January 2010, I have saved 153 to-do lists on my computer. There is a list of books read in the past decade (annotated), a list of books I want to read (ever-expanding), a list of movies to watch (slower-growing). There is a list of great quotations, a list of great websites, a list of rejections I received in college, and a list entitled “Things I Do,” which at that time included a writing group, a cooking class, two book clubs, and volunteering. There is also a list entitled “Things I Love.” On this one: the subway, running outside, “radio/podcasts,” books, apples, and, indeed, making lists.

This computer record is a small fraction of the lists I have composed. Most have disintegrated or been otherwise lost: scrawled in the back pages of notebooks, in the margins of magazine articles, on tissues, on sanitary napkin covers, on the back of my hand. There are only 20 grocery lists on my computer desktop, most having been written by hand on post-it notes in several drafts. I find lists in jacket pockets and wadded into tiny, hardened balls after accidental washings along with my jeans. Lists are shredded in the zippers of my handbags and often fly away in the breeze.

To look at an old list is to feel unsettled: most of these items were not completed. Take “Winter Fun,” a list composed two falls ago. I did zero of the suggestions on this list. No—one item: “concerts” is vague enough to have included any number of shows I saw that winter. But “ice skating at the Museum of Natural History,” “BAM Music Festival,” “Museum of Comic and Cartoon Art – Archie exhibit,” “crazy Indian restaurant,” “fondue”—what was I doing that winter? I cooked perhaps four times. I installed a hook-and-eye lock on my bedroom doors to prevent my roommates’ dogs from continuing to defecate on my mattress. Mostly, I believe, I threw a number of ingredients into a bowl, called it a salad, and ate it on the couch while watching Entourage. I made it through all six seasons. That had not been on the list.

“The impulse to write things down is a peculiarly compulsive one, inexplicable to those who do not share it, useful only accidentally, only secondarily, in the way that any compulsion tries to justify itself,” Joan Didion writes in her essay “On Keeping a Notebook.”

I suppose that it begins or does not begin in the cradle. Although I have felt compelled to write things down since I was five years old, I doubt that my daughter ever will, for she is a singularly blessed and accepting child, delighted with life exactly as life presents itself to her, unafraid to go to sleep and unafraid to wake up. Keepers of private notebooks are a different breed altogether, lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss.

This essay is one of the most eloquent and true I have ever read, by Didion or anyone else. Her self-analysis feels somehow pointed, as if she is explaining not just her own psychology, but also mine. Like Didion’s scribbling in notebooks, my list-keeping is done largely in secret. It is a squirreling-away—there is the hunching over, the shielding from view.

Notebooks and lists are, also, both the purview of the anxious. It is the moments in which there is too much energy to handle that necessitate a reversion to the page. These moments have the feel of those before a thunderstorm, when the air is oppressive and electric. Instead of erupting in tantrum, in lamentable “freakout,” the secretive writer scrambles for a pen and any paperlike substance and scribbles with frenzied energy. It is a momentary solution: a sealing-away of apprehension, or a shedding of it, one or the other.

Instead of erupting in tantrum, in lamentable “freakout,” the secretive writer scrambles for a pen and any paperlike substance and scribbles with frenzied energy.

But list-makers and notebook-keepers are different breeds, motivated by different anxieties. Unlike the list’s contents, the notebook’s are tactile bits of others’ lives: quotations, mannerisms, clothing. From Didion’s notebook: “‘That woman Estelle is partly the reason why George Sharp and I are separated today.’ Dirty crepe-de-Chine wrapper, hotel bar, Wilmington RR, 9:45 a.m. August Monday morning.”

Whereas the list is blatantly self-centered. Take a particularly painful example, a list entitled “Rejections!”—exclamation point included—that I kept in college. Among 24 items are two mortifying rebuffs by boys, seven internship turn-downs, three nos from a cappella groups, and two job declinations. I was rejected from volunteering as an usher during an alumni reunion, and from volunteering to drive a van during freshman orientation. What did it mean that I couldn’t be entrusted to drive a van? A sense of failure supplanted my wobbly sense of self, and this list was an attempt to regain control. Take the forced cheer of the exclamation point in the title: Rejections! Or the inclusion of silly items, like “Teacher of the Year.” My high school biology teacher hadn’t won an award for which I had nominated him, a loss unrelated to me and that did not affect my mood in any way. And to list it alongside “Jake” was to imply that, when I wrote one of my best friends a letter divulging my intense longing for him and he wrote back, after several days, that he was uninterested, it was equally unimportant.

Didion makes clear that the notebook is only apparently outwardly directed. At its core, it is, like the list, about the writer. But to dig beneath the surface is to discover a greater chasm. Notebooks are written in order to be read. “Remember what it was to be me: that is always the point,” Didion writes in “On Keeping a Notebook.” Those tactile bits of life are not meant to preserve the stranger, but to preserve the writer in her own memory—to enable her to recreate that scene, crepe-de-Chine wrapper by crepe-de-Chine wrapper. Rereading old notebooks, you collapse the distance between your present life and your multiple pasts. It is an immersion in the histories you chose, at one moment, to preserve.

To look at old lists, stupidly saved on one’s computer, is to see clearly what they were meant to help you ignore. Rereading the list of rejections, its whimsicality now an obvious sham, nauseates me. Even the to-do lists are unsettling to revisit: doing so reignites the anxiety in which they were written, or incites guilt over items forsaken. I do not like to recall the number of hours I sat in front of the television between December 2009 and March 2010, missing out on all the “Winter Fun.”

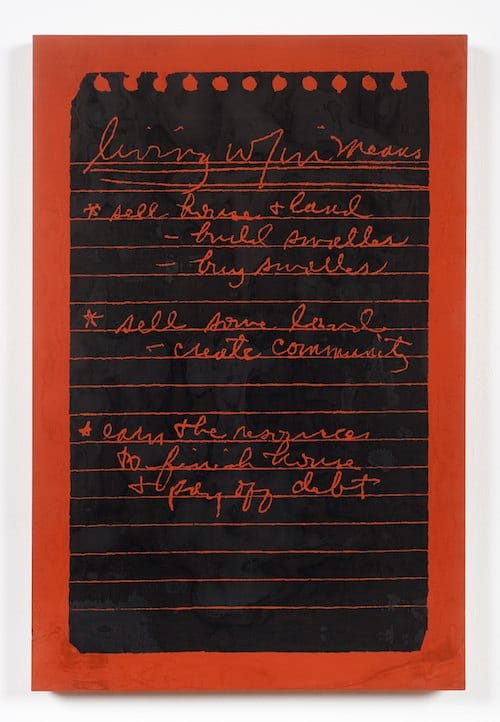

But what of the lists composed in anticipation—lists of goals and dreams, plans that promise contentment, even joy? I have unearthed one that is almost too embarrassing to type, but I trust you implicitly:

One day, I will:

- Go to TED

- Be published in the New Yorker

- Meet Ira Glass

- Work for This American Life

These ambitions, written only a year ago, are painful now to retype. I don’t remember the moment I composed this, but I can conjure the core anxiety clearly, because it is one I still have: that I will fail. By listing, with certainty, the accomplishments of my future self, I hope to plaster over panic that I will achieve nothing close to them. The list composed in anticipation is an antidote to the current life. It contains the ingredients of a future, perfect self.

The notebook-keeper wants to remember. “I think we are well advised to keep on nodding terms with the people we used to be,” Didion writes, “whether we find them attractive company or not. Otherwise they turn up unannounced and surprise us, come hammering on the mind’s door at 4 a.m. of a bad night and demand to know who deserted them, who betrayed them, who is going to make amends.” Though she may willingly evolve, she can appreciate that her past selves are still nested within her. But the list-keeper wants to forget. She worries that she will never evolve—never learn to roast chicken, never leave New York, never find love—and longs to erase the evidence that this is so.