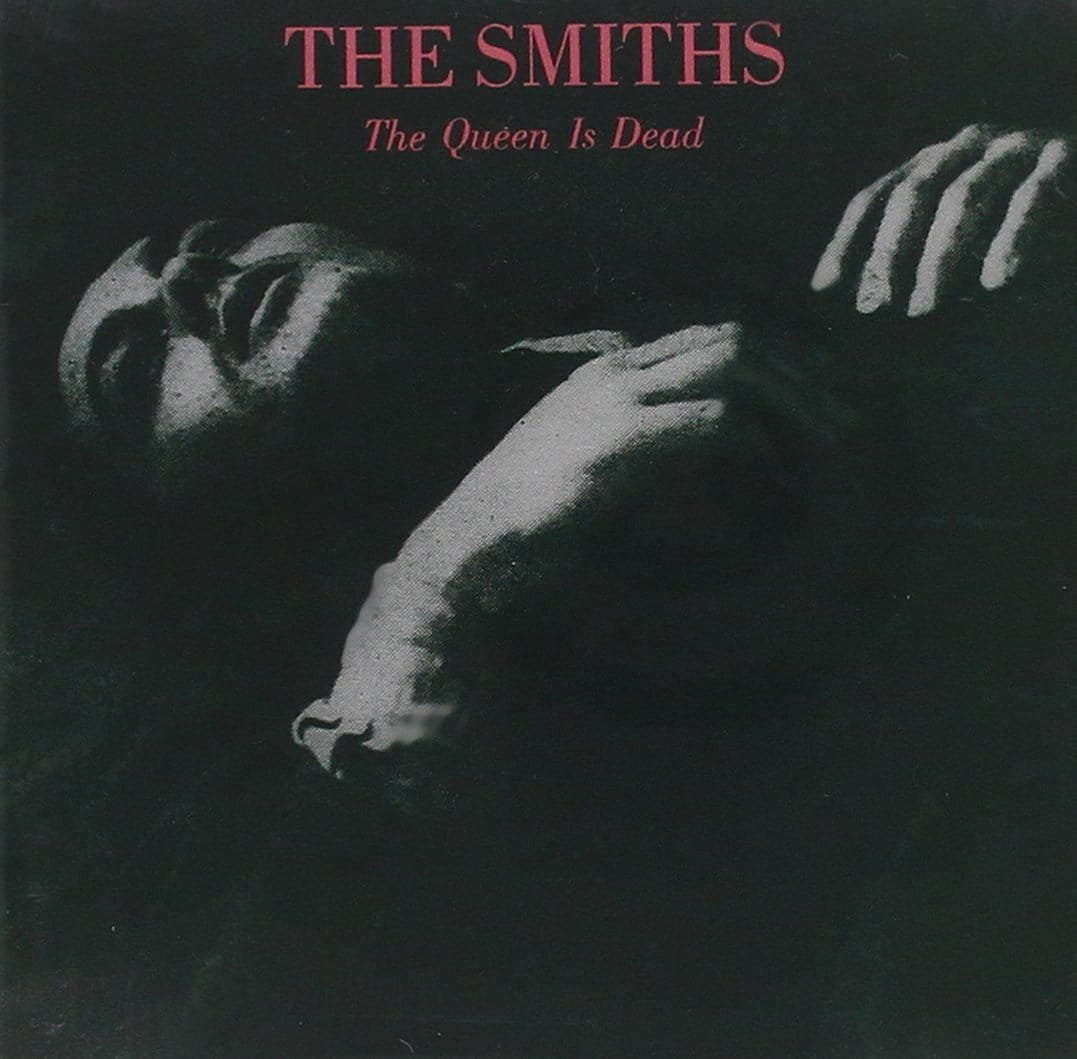

The Queen Is Dead

Love, swimming pools, road trips, and burritos: remembering the Smiths’ classic album.

The Queen Is Dead (Take Me Back to Dear Old Blighty) [Medley]

Tequila does not so much swim through one’s blood as set it on fire. It is kindling and even tastes like it. You pour it past your lips and almost immediately gag since you’re unused to such an alien and obviously dangerous taste. Your body wants to reject it, and your gorge rises fast and angry and with frightening urgency as the flames douse your throat but your friend advises, sagely, but perhaps a touch too late (where were you before I downed the shot?) to suck the lime slice.

Later, against the wall, itself throbbing because you stand under the speaker and your ears hear only some tintinnabulation of constant silvery threads and you turn to the girl next to you and grab her arm and open your mouth and speak words you can’t even hear yourself say and nod encouragingly toward the dance floor where it is dark and filled with smoke and shuffling bodies and sweat and she, because she knows better, pulls harshly away and scowls and says something back, something still unheard, but the meaning is clear. You did it because you felt you had to, or were supposed to, and the rebuke hurts in ways you never counted on.

You will awake tomorrow unable to move, remembering it as one of the best nights of your life.

Frankly, Mr. Shankly

The car seats are torn, and the foam rubber beneath is dry and browning, as if the cut has scabbed over several times only to be ripped open again and again. It is your annual mid-Summer escape from the boredom of your post-teenage existence to the cool, northern beaches of California. San Luis Obispo is somewhere far away, past the brown hills and dead trees and waves of heat that make the still, silent sky look like it’s melting.

You wish you owned a car of your own, something to spirit you away from everything at your whim, without relying on someone else’s kindness. It’s July and triple-digit unbearable back home. Even here, halfway to the sand and surf, the heat is oppressive. The car has no A/C and the wind that mixes your steel wool hair like an eggbeater feels like an oven on your neck.

You push your feet out the window, flip-flops abandoned on the floorboard, and gaze at rambling wooden fences that appear to have been assembled by children of questionable intelligence, every rough-hewn plank shoddy and falling apart. The car rises through the hills slowly, higher and higher until the rolling landscape falls away as if it was a backdrop all along.

Suddenly, a panorama of the valley reveals itself, a view of the place you are from in painted swaths of gold and tan and brown. Before you realize it, you are cooing like a baby at the sight and the car slows and stops, hanging on the lip of the road.

You sit inside the car and look down on everything, literally. The vast, broad cuts in the earth, the smooth, soft hilltops, the wind-tossed grasses rustling like starched dress shirts, cascading in iridescent waves. The beauty of it, you think, lies in the absence of any sight of humanity.

‘Pretty,’ the driver says to you, unnecessarily.

You agree anyway, nodding in silence, feeling the injustice of that word but unable to think of anything better. Your home is beautiful, yes, but you hate that place and the fact that you came from there. So this one small concession is all you can manage, knowing it is inadequate but willing to live with that.

I Know It’s Over

It was called ‘Suicide Swings’ and it went like this: Find a community park with the biggest swing set. The best are the kind made of arched pipes like outstretched legs, and from the loins hang the swings. The swings must be connected using chains, the kind that pinch and catch the skin.

Suicide Swings must be played at night, on sultry summer evenings past midnight. Stop at 7-11 beforehand and pick up two pints of Häagen Dazs honey vanilla ice cream.

You and your friends each occupy a swing, and you sit facing alternate directions so that beside you, on either side, you see feet.

You begin swinging slowly at first, feeling the wind caress your face, cool and dry, and the sky is wide and dark and dusted with stars. The swings cry like gulls, the chains and s-links straining from the weight of almost-adults who should know better.

At the highest arch, you begin to subtly, so subtly swing your legs from side to side. Your pendulum becomes a parabola, in wider and wider arcs, and you are only dimly aware of the actions of those nearest you because they scream by in the opposite direction, disappearing behind you where their trajectory cannot be guessed. An exhilaration of fear infuses you and you welcome it eagerly. It means you are alive tonight, giddy and breathless, laughing and flinching with equal fervor.

You can feel them now, your friends, their heavy bulks pushing the air against you. You know what you’re in for—the unexpected and violent impact of body against body, the ejection and arc and impact, the expulsion of all the air in your lungs and a dazed uncertainty when you finally hit the sand, embraced by pain. You anticipate it. You crave it. A desire you’ll never be able to explain.

Closer and closer they come.

Never Had No One Ever

You are naked in your own back yard. The sun is overhead like a heat lamp on French fries, so bright that your closed eyelids turn red and the bright, hard pinprick of white burns the skin.

Your brother hooked up a pair of old speakers out here for the occasional summer party. He had to crawl through the tight attic space to run the wires, and you have to go into his sanctuary and touch his HiFi, the Pioneer receiver rigged to get the better stations from Los Angeles, the college stations, the stations that play long strings of music you’ll never hear in your stupid, backwards, ugly little valley town.

You feel dirty and sexy and nasty. No one can see you unless they look over the fences, and no one will do that, but you imagine that passing pilots will look down and see you on the deck around the blue pool, your hand on your dick, lathered with suntan oil, the smell of coconut and banana strong and sickening. Your whole body is hot and shards of the dry wood bite your ass. You stroke hard and fast with passion and anger, anger about this and that and wanting release in the only way available to you.

A stronger, more intense heat splashes on your groin and belly and too quickly, it’s all over. Just like always.

Cemetry Gates

It’s not your dog. You hate your dog, or rather, your mother’s goddamn dog. The poodle that shakes and barks and looks like some black boiling bush. This is the dog of the guy up the street, the guy at college, who had to leave his dog behind and now his mother doesn’t know what to do with him, the white shiny dog up the street.

So she lets you and assorted others (not in college) take the dog to the wide lawn in the middle of the track at the Junior High School and you know, suddenly, what a real dog is like.

His eyes are bright and his tongue is warm and wet and soft on you face. When he barks, it doesn’t sound harsh and angry, it sounds like a shout of joy, an audible thing made of caramel. You throw the stick you found on the way, the one you used to write a dirty word on the sidewalk on the way to the track, over and over and watch him, effortlessly, perfectly, retrieve it and bring it back just to you, putting it in your hand, and waiting for you to help him have fun, more fun, endless fun.

Bigmouth Strikes Again

Your friend R.B. returns from Sav-On Drugs to the record store where you both work. He’s carrying a small white plastic bag.

‘What’d you get?’

‘Condoms.’

You look in the bag. ‘There must be a hundred condoms in there!’

He smiles big, says nothing.

‘What would anyone possibly need that many condoms for?’

His brow wrinkles in a way that needs no further explanation regarding his station and yours in the small kingdom of the record store.

The Boy With the Thorn in His Side

Deep inside the closet of your own making, you sit alone on a bench at the Mall’s food court. You look across the wide, sad, noisy place and see, far away, that guy. You saw him earlier, at Miller’s Outpost, where you were looking at faux Hawaiian shirts and he was looking at parachute pants.

His hair is dark and parted severely right down the center of his head so it hangs loosely precise. He has blue eyes, which even from here you can see are like turquoise. His skin is tanned, dark, liquid. He talks in an animated fashion with someone whose back is to you. You watch how his mouth moves, the line of his jaw, the way his neck stretches. His lips curl into a smile and his teeth are white against the copper. He wears a T-shirt striped like a bee. You feel a mingling of emotions, and you sense the nervous tick of someone timing the looking-away before the other sees the looking-at. Your breath is shallow and your mouth is dry because he is the most beautiful creature you have ever beheld in your life.

It is a perfect moment of sex and pain and wonderment and shame. He never even looks at you.

Vicar in a Tutu

You sit beside a Catholic friend in her truck a week before her wedding. It will be a grand, huge, all-encompassing affair with incense and candles and intoned prayers to almighty God spoken in hushed but exalted reverence. She has four brothers and four sisters and, she explains, she wants a big family because big families bring big love. She says it exactly that way, ‘A big family brings big love!’ and you get the feeling that she isn’t being sarcastic—in the way you would be. You have one brother who, you know for a fact, hates your guts and a half-sister you have not seen in six years. You think there may be a Bible somewhere in your house but you aren’t sure. You certainly have never opened it.

Your friends, almost without exception, are devout Christians. Something happened recently, some awakening that infected all of them in your large, mostly white, entirely too heterosexual High School. Some are Southern Baptists, and they speak in tongues (or so you have heard). Some are Calvary Chapel, a weird non-denominational but entirely Christian church located in a warehouse or something where cool deacons preach peace, man, and understanding and love through Christ, if that’s your bag. Some are Catholic. As far as you know, there are no Jews in Bakersfield, California.

‘So,’ you ask, looking through the bug-crusted windshield, your finger tip playing with the seam of your Sears ‘Husky’ Jeans, ‘you believe that God is a man with a long flowing beard sitting on a throne in the clouds.’

‘Yes,’ she says with vehemence and absolute certainty.

‘And he sits there and judges each of us in everything that we do.’

‘Yes,’ she states with clarity of mind and a frightening lucidity.

‘And if I was, like, a killer. A murderer. And all my life I killed people for… whatever. And I’m on my deathbed. And a priest comes and tells me that if I confess my sins and accept Jesus Christ as my personal savior that I’ll still go to heaven, even though I spent my entire life randomly killing people.’

‘Yes,’ she says with finality and a sense of order in a chaotic world.

You feel your agnosticism swelling like a blood blister.

There Is a Light That Never Goes Out

You sit in your kitchen and your best friend sits across from you. (And the guy you suspect of being his lover sits beside you.) It’s 4PM on a Wednesday. You’re sitting around a table with a Formica top. You have just experienced having your car totaled in an intersection near the record store where you work and, upon arriving home, you have been told by your best friend (as his lover looks on) that he wants you to move out (you can see the smile creeping across the lover’s fat, ugly lips).

As compensation, or perhaps (you suspect) because he simply enjoys getting high all the time anyway, your best friend and ex-roommate offers to share his pot with you. There is no pipe; so he illustrates the soda can method, involving a Pepsi can crimped just so in its center to create a kind of well along its waist, then puncturing the well with a fork. Only a few holes, small, and carefully distanced from each other. Then you place a small pile of weed over the holes, hold the mouth of the can to your own, hover a lighter above the stash, flick your Bic and tentatively welcome your first hit ever.

You suck in a lungful of ash and stems and grit and smoke and, carefully, eyes watering, you hold the harsh, burning dream-stuff inside as a giddy belch of helium fills you up. You can feel yourself getting lighter and lighter and the darkness seems suddenly comforting, or more comforting, or something. The glint of the day that reaches its fingers through the blinds dance on your eyes like silver splashes, or darts that pierce your retinas and cause sparks to shoot from the backs of your eyeballs.

‘How does it feel?’

You look at your best friend with red-rimmed eyes and a mouthful of blue smoke. ‘Fuck you.’

He suggests going out for burritos.

Some Girls Are Bigger Than Others

You are returning from San Francisco with Mike, whom you have known for some years. You are driving along I-5, a vast stretch of nothingness that links the entire west coast of the United States from Washington to Tijuana, which you visited once upon a time and returned from with a marionette and a tiger-eye ring that turned your finger green.

The silence of the car mirrors the dead hatred you feel inside having spent too many hours with the guy. The problem is that you are too alike, both trying hard to be funny, both filled with anger and resentment, both raised by single mothers, both with older brothers you both wish to emulate and distance from with equal desire.

You’re hungry. The car, a 1977 Mercury Comet with a stripped vinyl top and killer cassette deck, climbs up and down the mountains on barely-there tires and probably too little coolant in the radiator, but the inherent dangers of the situation never even occur to you. You grit your teeth because you know you need to open your mouth to ask a question of the person you’d much rather simply kick out of the car and leave stranded on the side of the highway like a run over rabbit.

‘Do you want to eat?’ The words come out strained and quiet.

‘Where?’

Jesus! Can’t he just answer a simply fucking yes-or-no question with a simple fucking yes-or-no?

But you are cool. You are smooth. The past days of constant contests of wit and sarcasm have not dulled your finely tuned intellect. ‘Pizza?’

‘Pizza hurts my braces.’

Your eyes narrow and you grip the wheel tighter with your sweaty palms. ‘Then where can we eat?’ You stress the word ‘can’ and he doesn’t miss the annoyance in your tone. How could he? He is you.

‘I don’t care.’

‘But you just said you can’t eat pizza.’

‘Do you have a toothbrush?’

‘Of course I have a toothbrush. Why would I go on vacation for a weekend and not bring a toothbrush? Do you think I’m the kind of person who would go out of town for an extended period and eat sushi and pasta and tuna salad and get all that crammed up in my gums and then not bring a toothbrush with me? Like I enjoy having bad breath? Like I enjoy walking around with that woolly feeling on my teeth? Like I’m some kind of filthy, disgusting creep who doesn’t practice dental hygiene like any other civilized member of society? What kind of fucking weirdo do you think I am, anyway?’

Something darts across the road and you hear and feel its bones rattling around the right front wheel well. You glance in the rearview mirror to see if you can watch the remnants of whatever it was emerge behind you in a crimson spray of guts and fur. You imagine the sharp little bones embedding themselves in your tires and the wet gore hanging in strands, flapping behind the Comet on this deserted stretch of highway.

You look over at Mike. He’s smiling, and you realize you are too.

You immediately pull over to the side of the road so you can both examine what’s left of the creature, forgetting that you hated him while lost in the reverie of shared morbid satisfaction.