The Rooster Nonfiction Pop-up: Wrap-up

A final discussion with Sarah Hepola, Rosecrans Baldwin, and Andrew Womack about the three memoirs we read this month.

Welcome to our first-ever Rooster Nonfiction Pop-up, brought to you by the organizers of the Tournament of Books.

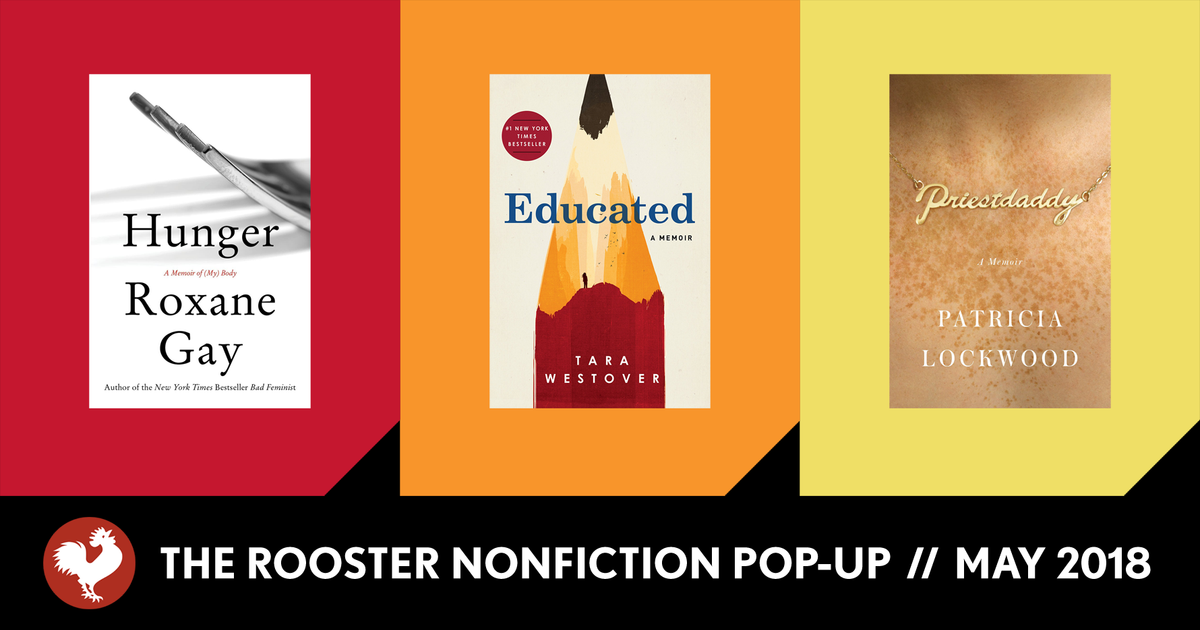

All month long we discussed three recent works of nonfiction. To choose which books we read this month, we asked this year’s ToB readers for suggestions back in March. We narrowed that list down to a single genre—memoir—and our readers voted to decide which three books we’d read for this event, and here they are: Hunger by Roxane Gay, Educated by Tara Westover, and Priestdaddy by Patricia Lockwood. You can see the full list of nonfiction contenders here.

Unlike the Tournament of Books and the Rooster Summer Reading Challenge, the Rooster Nonfiction Pop-up isn’t a competition—only a discussion about these three memoirs.

- Catch up on previous chats: Hunger (first half, second half); Educated (first half, second half); Priestdaddy (first half, second half)

- Jump into today’s discussion in the comments

Please note: We receive a cut from purchases made through the book links in this article.

Rosecrans Baldwin: Welcome, everyone, to the last day of our first-ever Tournament of Books Nonfiction Pop-up. Over the course of this month we read three memoirs, similar and different in a bunch of ways. We thought we’d spend the last day talking about some of those connections, about memoir generally, and anything else that came up that we didn’t get a chance to discuss. Please join us in the comments and let us know what you think!

Sarah Hepola is the author of the bestselling memoir, Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, The Guardian, Elle, Glamour, BuzzFeed, Jezebel, and Salon, where she was an editor. She has been a contributor to The Morning News for more than a decade. She lives in Dallas, and she is currently working on a second book. Please don’t ask her about it.

Rosecrans Baldwin is a founding editor of The Morning News. His latest novel is The Last Kid Left (NPR's Best Books of the Year).

Andrew Womack is a founding editor of The Morning News.

Andrew, Sarah, I think one thing I’ve all struggled with all month, but we haven’t really talked about in the group, is the value of memoir to us as readers. I’m a novel reader first, poetry second, general nonfiction and history third, followed in random order by memoir, biography, and short stories. So for me comparing memoir to fiction isn’t apples and oranges, but it’s also not apples and submarines. I just don’t get as much out of a memoir as I do from other forms of literature. And within memoir, I tend to get more on average from specific types of memoir (travel diaries from previous eras) than others (coming-of-age stories from the last 30 years). Do you two organize things this way?

Sarah Hepola: I am obsessed with other people’s stories. I want to know their secrets, and their contradictions, and their tiny hypocrisies and regrets. Memoir can be a great vehicle for that kind of intimacy, although I will readily admit there are too many memoirs, and the material often isn’t pushed as hard as it should be.

Rosecrans: That’s a great point. Maybe that’s why I don’t read more memoir.

Sarah: It’s a populist genre, so technically anyone can write a memoir, which isn’t always a good thing. But when a memoir is clicking, I get a rush like infatuation. I get that same exhilaration from a good novel, or nonfiction, or poetry. I don’t care about the genre. I’m just singularly preoccupied with human behavior and the interior life of another person. This is something literature can give us that television and movies cannot. Netflix is so damn good right now. But I don’t get that immersive experience of being inside a person’s mind, getting to see the world through their eyes. I want the inward plunge, all the way down.

Andrew Womack: I feel fairly comfortable comparing fiction and memoir, though only in specific ways. Like everyone here (I think), I love good fiction, but most fiction is bad. Here’s why: It’s human behavior, as Sarah mentions. For me, that’s about how true-to-life people are, as depicted in these books. Now, when we’re talking about fiction that is almost entirely unbound to true life—speculative fiction, for example—that’s one thing, and the normal rules of human behavior apply in a different way. I go into fiction knowing this is not real; however, one wrong move on the book’s part will throw me, and it’s going to be hard to pull me back. With memoir, I won’t even notice, because the premise sets me up to believe it happened. And even if what happens is outlandish, I still won’t doubt it. So, the rules are different, but the end result—enjoyment of the work—is where I feel the pathways meet again.

Rosecrans: Andrew, discussing Priestdaddy in the comments section last week, you said, “memoir offers an extra level of profundity.” I don’t agree personally, so I wonder if that holds true in other areas in your life when you encounter nonfiction? Does a movie mean more to you when it’s a personal documentary?

Andrew: Again, only in very specific ways. It’s not going to automatically mean more to me simply because it’s a personal documentary. But my suspension of disbelief means I won’t judge it as harshly as I do when I’m watching a fictional work—most of which I stop watching around 20 or 30 minutes in, at which point I Google to find out how it ends. As with fiction, most movies are bad.

Rosecrans: Wow. Really? What’s the last movie you did that with?

Andrew: Phantom Thread. Actually, that one backfired on me, because after I read the ending I had to see it for myself, and I’m glad I did, because it delivered—actually “delivered” is the wrong word here, as that would imply the premise made it worth the two hours. Come to think of it, the same thing happened for me with There Will Be Blood. I left it running in another room for an hour or so, checked the Wikipedia entry, and went back to it.

Rosecrans: That confirms it, I can never watch a movie with you.

Andrew: This is literally true, because I would be on the internet, in an adjacent room because that’s etiquette.

Rosecrans: I guess I’m interested in this because I tend to have a different reaction when it comes to books; fiction gives me that added depth more frequently. At the same time, for the last eight years, I’ve watched every episode of RuPaul’s Drag Race when it airs in part because of the contestants’ testimonies and stories, the emotional hook of hearing about their lives. Sarah, what about you?

When you reach the end of that book (spoiler alert), and you realize the person who wrote it has died—it’s just devastating. It was real. I want both those experiences: to be knocked out by an invented world, and to be knocked out by the actual world.

Sarah: I think people want to know about other people. We’re drawn to compelling characters, whether they’re on a reality show about drag queens or a fictional show about ad men in the ‘60s or a memoir about a woman and her tangled relationship with food and desire. I think we want to illuminate our own experience, and expand our understanding. I agree that fiction might be able to go deeper, or wider perhaps, because it gives you more characters to explore in depth. For me, there is probably no greater reader experience than a thick, multi-character novel. It feels so real. But I recently read When Breath Becomes Air, Paul Kalanithi’s memoir about being diagnosed with cancer while working as a neuroscientist. When you reach the end of that book (spoiler alert), and you realize the person who wrote it has died—it’s just devastating. It was real. I want both those experiences: to be knocked out by an invented world, and to be knocked out by the actual world.

Andrew: Format in memoir is, I think, quite important, and I feel like we saw a nice range this month, with Hunger’s brief chapters, each focused on a single idea, and Priestdaddy’s nonlinear storytelling that culminates in a bigger idea. How did you both feel the format of Educated fit alongside that? Are there examples of other memoirs with formats you’ve thought were particularly successful?

Rosecrans: I love a diary, especially when pushed to its limits. The obvious touchstone is Anne Frank, but I like traveler accounts (Who Am I and Where Is Home? by Andrea Jackson), fictional interpretations (Tanizaki’s The Key), diaries about a city someone loves (Istanbul by Orhan Pamuk). When the story’s tied to something bigger, I can be very moved. So I guess that’s why Educated, for all its strengths, didn’t click with me. For all its strangeness, it wasn’t personal enough, but it also wasn’t grand enough, either.

Sarah: I liked Educated, although I would agree the story was told at an emotional remove. I wondered if that was either Westover’s personality (she’s an academic) or a necessary distance from such a messed-up childhood. The book has a fairly standard chronological structure. I won’t knock that approach; I’m sure I’ll use it one day. What’s nice about memoir, though, is that it’s a very elastic form, which can be bent and twisted to accommodate the author’s voice. Short chapters, random tangents, long diary entries. One of my favorite memoirs is Tiny Beautiful Things by Cheryl Strayed, which isn’t technically a memoir. It’s a collection of advice columns she wrote on The Rumpus as part of the “Dear Sugar” feature. Some of the letters are short, some go on and on. What matters is the voice. The voice is honest, electric, riveting. It’s one of things where I just know—wherever this woman goes, I’m going to follow.

Andrew: A big topic I feel like we were all touching on all month was about characters and how believable (or not) they are, and about what that does to how willing we are to suspend our disbelief. How did you feel about the believability of the characters you met in these books this month? Did you buy into them, and did it matter?

Sarah: I do get tangled up in this question, and I don’t know if it’s because I often write in this genre, or if it’s a personality quirk, like someone who always has to check the expiration date before drinking the milk (which I never do, by the way). With Hunger, I trusted Gay from the beginning. Maybe because I knew her work from elsewhere. With the other two, it’s like I had to spend a certain amount of time sniffing around: How can you remember all this stuff from childhood? Isn’t this a little too detailed? Or, why would a real person say that? That makes no sense. This constant voice inhibited the experience of both those books for me. By the way, I often do something similar with fiction. Like, if a novelist is writing about a character cheating on her husband, I’m thinking: OMG did she have an affair?

Rosecrans: I have that experience all the time.

Andrew: Sounds like you could clear that up with a healthy dose of reading more memoir.

Rosecrans: I’m beginning to think the same thing!

Sarah: One of the signs of a great reading experience for me is when I stop doing that. When my overthinking, double-thinking mind hangs it up for the day, and I’m just in the story.

Rosecrans: Maybe I’m just a sucker, but the believability issue is rarely a problem for me, unless something’s glaringly false or implausible. Even in Educated, when things went bananas, I never really doubted Westover’s account.

That said, I remember when David Sedaris started writing memoir pieces for the New Yorker and people wanted his work, which I believe by that point had been shown to contain plenty of fiction, to meet the magazine’s fact-checking standards for journalism. And I remember being surprised to realize I felt glad to hear that, that he’d be held to a higher standard, because I’d been sincerely bummed to learn that some of Santaland Diaries and Naked were fabricated—at a time when so many writers working in experimental nonfiction don’t feel compelled to make shit up.

Sarah: One thing I’m surprised nobody’s mentioned yet is that all these memoirs were written by women. That’s typical for this genre. Memoir is dominated by female voices, and I think a lot of men are reluctant to read memoirs by women because they assume they won’t relate to them. I know I can’t ask either of you to speak for your gender, but I’d be curious to hear your thoughts on that.

Rosecrans: What’s up, dudes? Be you so afraid? I mean, I’ve already said I’m generally not a big reader of memoirs, but according to my reading spreadsheet, the last one I read by a dude was in 2016 (Barbarian Days by William Finnegan), whereas there have been several memoirs by women more recently.

Andrew: I’d never thought about men being reluctant to read memoirs by women, but of course I see what you mean. I feel like the process of reading anything is about feeling that you’ve expanded your vision of the world. Even if you’re reading something that merely validates your existing views, the effect is still the same.

Memoir often gets dragged along in the net that includes social media, reality TV, selfies, etc. I would argue that a good memoir is the opposite of shallow and narcissistic, that it gets underneath the surface and looks outward as much as inward.

Specifically with regard to memoir, however, it gives readers an opportunity to see through someone else’s eyes, in a way you otherwise couldn’t. I felt this was particularly true with Hunger. I do not know what it is like to live in this world as an obese, queer, black woman; nor do I know what it is like after reading the book. But what I do know a little more as a result of having read this book is what it is like to not live as myself. In this way, memoir can wear away at the hard exterior of our egos, persuading us to be empathetic after that brief dip into another’s real-life experiences.

I’m not sure if it’s only men, but I do wonder if it’s that addiction to ego, that refusal to want to see another side, that repels some readers.

Sarah: A common complaint about our culture is that we’re narcissistic, constantly focusing the lens on ourselves. Memoir often gets dragged along in the net that includes social media, reality TV, selfies, etc. I would argue that a good memoir is the opposite of shallow and narcissistic, that it gets underneath the surface and looks outward as much as inward, but maybe we are too self-obsessed. I mean, I’m currently in the process of writing a second memoir, for crying out loud. What do you guys think about all this? Does memoir get an unfair rap, or did it earn this rep?

Andrew: The intersection of memoir and Instagram influencer, I like it. For a literary equivalent of only that—of only the outwardly celebrated life of the author—my first assumption is that it sounds very terrible. I’d be wrong, though, because it would come down to how we interpret it. A favorite Twitter feed, Andy’s Diary, posts snippets from The Andy Warhol Diaries, and while I’m not sure I’d get far if I were to sit down with the entire book, these clips work really well as random observations on art and celebrity. Then again, it helps that it’s Warhol. So, that’s a prerequisite.

You don’t know about people. Everybody just does their own stuff on their own scale. 5/25/84May 25, 2018

Rosecrans: Memoir, done right, makes humanity a little richer. It makes the specific more general, it takes a single life and holds it up as an example of a much bigger story. I think that’s a good thing. A well-done memoir makes me feel better about people, when normally I feel pretty lousy. So I guess I don’t really care about the self-obsession accusation. Humans being selfish is a pretty old story. But I think publishing a memoir, a good one, when it meets the right reader, can feel like a gift. And that’s why I love great books of any genre; they nourish me. If a memoir can step up and do that, I want more.

Andrew: Thank you, Rosecrans—and a huge thanks to Sarah Hepola for spending her May talking memoir with us. Make sure to follow her on Twitter and check out her memoir Blackout: Remembering the Things I Drank to Forget. Thank you also to our Sustaining Members, who made this event possible. You’ve heard us say it before, but it warrants saying again: Our members are the sole reason we're able to continue bringing you the Tournament of Books and these new events. If you're not already a Sustaining Member, please take a moment to find out why we ask for your help, and consider becoming a member or making a one-time donation.

I know the three of us had a lot of fun up here this month, and we all got many things out of the memoirs we read. And to the commentariat: I hope you did as well.

With that, our first Rooster Nonfiction Pop-up is in the books. We’ll be back next week to welcome everyone to the 2018 Rooster Summer Reading Challenge. To be alerted about that, I recommend signing up for the Rooster Newsletter below—and we’ll see you soon!

Subscribe to the Rooster newsletter

You will receive email from The Tournament of Books. Opt out at any time. (View our privacy policy.)