The Statue in the Corner

It's time once again for our annual Halloween ritual, where we dust off a classic urban legend and reanimate it with a few new endings.

The Beginning

Emily is babysitting for a wealthy family. It’s her first time at the house, and before leaving, the father tells her that after she puts the children to bed, she can watch TV in the children’s game room.

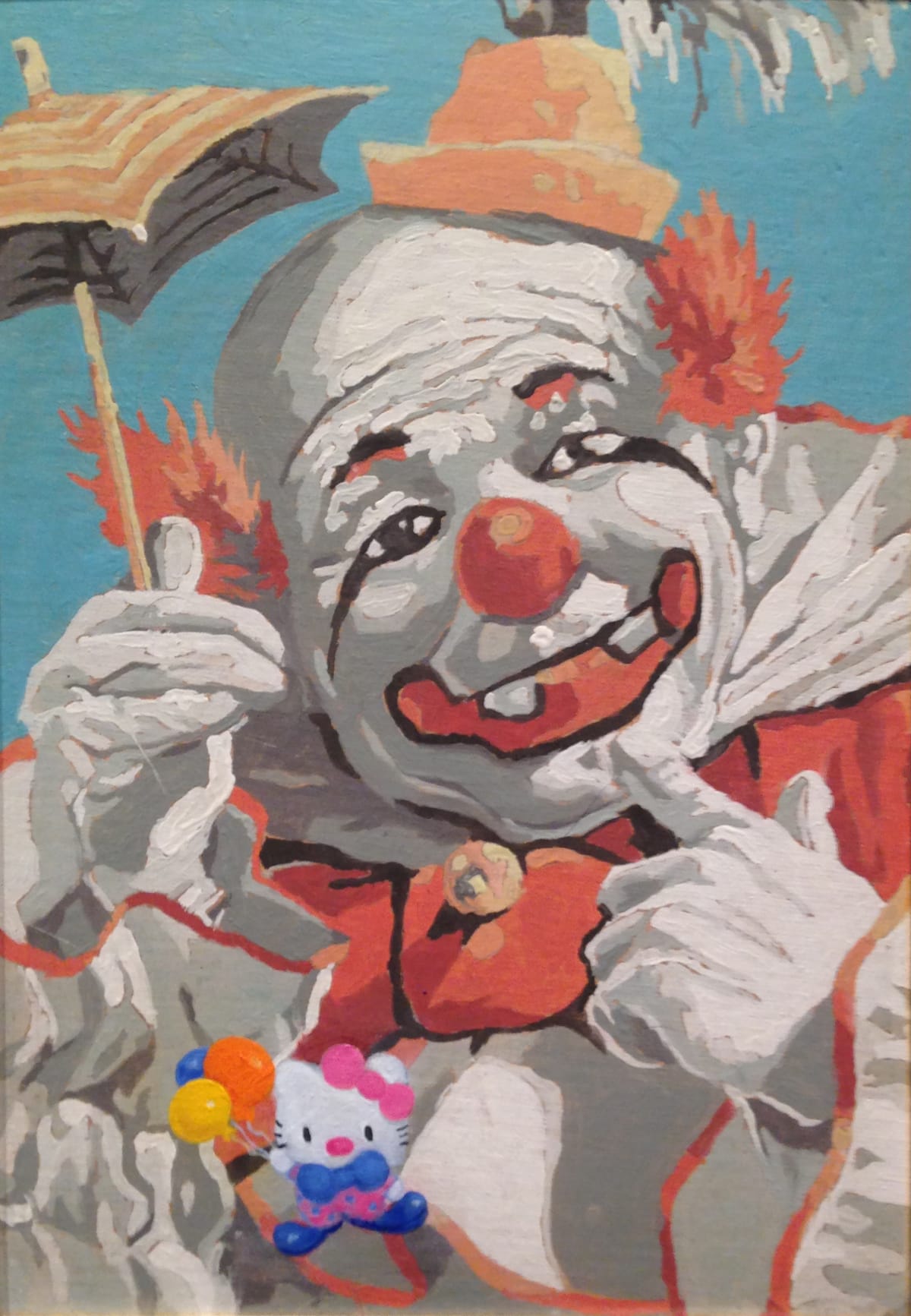

Later that night, after the children are asleep, Emily goes to the game room, turns on the TV, and sits down to watch a show. But she can’t concentrate on what she’s watching—her attention keeps shifting to the life-size clown statue in the corner of the room. She tries to ignore it, but the statue draws her attention back, over and over. Then her phone rings—it’s the father, calling to check on everyone.

“The children are asleep,” Emily replies, “and I’m just watching a show. Hey, would you mind if I watched TV in another room? The clown statue is kind of creeping me out.”

“The what? Listen to me: Get the kids and get out of the house now.”

Kevin Guilfoile

The father hangs up. “That was weird,” Emily thinks. She gets up and inspects the clown statue. There doesn’t seem to be anything unusual about it. She dials 311, the non-emergency number.

“Oak Grove Police.”

“Hi, I’m babysitting and I just talked to the dad, and he sounded kind of wigged out. He’s at Mangia Restaurant on Hillside Avenue. I think he might be having a stroke or something.” The operator thanks Emily and says they’ll check it out.

Emily walks around the back of the clown. It seems old. The white face paint is chipping in places. The baggy costume, with shaggy colored spheres for buttons, smells of mildew. The pointed hat has a small hole in it, like a cigarette burn. The phone rings again.

“Are you the babysitter! This is the police. We ran the phone logs from your address. The last call didn’t come from the restaurant! It came from inside the house!”

“This happens sometimes when babysitters call here,” she says. “Everyone at the station gets a little ahead of themselves.”

“That was me calling you,” Emily says.

The dispatcher apologizes. “This happens sometimes when babysitters call here,” she says. “Everyone at the station gets a little ahead of themselves.”

Emily hangs up. She feels a little silly now, allowing herself to be frightened by a statue. She is just turning on the TV again when she hears a car in the driveway.

“Emily! Kids!” It’s the father running up the stairs. He opens the door to the game room. “Emily! I told you to get the kids out of the house! Good lord! Where is it?”

Emily points to the statue. The father turns to look at it and his face is transformed by relief.

“Oh thank god,” he says. “When you said a clown statue was scaring you, I naturally thought you were talking about a statue of Pierrot, the best-known creation of famed 19th-century pantomime Jean-Gaspard Deburau, who in 1836 murdered a boy on a Paris street with his walking stick. Ten years ago a Pierrot statue became possessed by the demonic spirit of Deburau and it killed my first wife and our three kids with an umbrella stand. I destroyed that statue and replaced it with this one of Canio, the clown from Pagliacci. Canio never killed anybody.”

But of course the father, who had never seen the end of Pagliacci, is wrong. Canio had killed several somebodies and our declining cultural IQ would claim another four bloody victims that night. There would be more in the weeks to follow as America, so afraid of exotic diseases and machete-wielding religious zealots and the declining price of Amazon stock would be too slow to realize that what we should really be afraid of, the thing that will truly one day bring an end to the Western commedia, is our own ignorance.

And clowns, obviously. Goes without saying, really. I mean I don’t have to spell that out. That clown shit is ridiculous.

Eric Feezell

“Why, Mr. Adams?!” asked Emily, a lump rising in her throat.

Like that, the clown’s mouth began to move. And its body came to life before her terror-filled eyes. And it began to sing. And the singing was terrible.

“Hey, batta batta, hey batta batta, hey batta! Hey, batta batta, hey batta batta, hey batta!”

“Oh. My. GOD!” she screamed.

It began dancing and whipping around its long brown hair, totally stoked on life.

“Hostess ding dong, ramma lamma ling long, Napoleon versus Pol Pot at ping pong!”

“Get the kids, run away!” Mr. Adams yelled from the other end of the line. “Get them out of there and run for your life, Emily!” His voice cracked: “It’s CLOWNTHONY KIEDIS!”

Clownthony Kiedis took off his clown shirt to reveal an Adonis torso covered in bronze body paint, with sculpted six-pack abs and bulging tattooed biceps. He slithered his tongue like a snake, arms outstretched, and began moving in on her. “Come to papa, little Everly Bear!”

She bolted barefoot to the kids’ room as Clownthony Kiedis gave shoutouts to several well-known Southern California urban centers.

“Leave me alone, weirdo!”

“Califooooorni-ay-AAAAAA!” bellowed Clownthony Kiedis, suplexing Emily onto the couch. Stripping her violently of her socks, he quickly chewed holes in them and converted them into gloves. Clownthony Kiedis then proceeded to stand on her back and pretend she was a surfboard while singing, “Selma, Alabama! State of Indiana! Dark bandana! Swank Louisiana!”

A gnarly wipeout by Clownthony Kiedis allowed Emily to escape. She bolted barefoot to the kids’ room as Clownthony Kiedis gave shoutouts to several well-known Southern California urban centers. Clownthony Kiedis trailed slowly behind as he segued into a horrible improvised vocal pattern that could only be described as the sonic equivalent of a rotting carcass.

Upon entering the room, she slammed the door and shoved a chair in front of it.

“Kids, wake up. We need to leave!” she yelled. Zebba-zebba-zoom, a-zoomba-zomma-zay could be heard repeatedly from the hallway. She put the phone back to her ear. “Mr. Adams, what is this thing and why is it making these awful sounds?”

“Have you not heard of scat?” asked an indignant voice through the door.

“Clownthony Kiedis!” explained Mr. Adams. “He’s an imaginary demon from my drug days! I went to Lollapalooza ’92, dropped 12 sugarcubes of liquid LSD, and peaked during the Chili Peppers’ set. At that moment, Clownthony Kiedis was born…”

“Suck my kiss!”

“He haunted my thoughts for years,” continued Mr. Adams, “never shutting up, constantly fake-scatting and trying to get me to go surfing with him. Until one day I decided to get laser removal on my tribal armband—the same tribal armband Anthony Kiedis has on his left bicep. With the removal of the tattoo, Clownthony Kiedis’s hold on my psyche began to fade. But not before he vowed revenge on my family, saying one day he would come back and—”

The call cut off. Panic rose in Emily’s chest. She ushered the children into a closet while Clownthony Kiedis banged at the door, “Psychic spies from China try to steal your mind elation!” She would have to face Clownthony Kiedis on her own. Surveying the room for a weapon, her fear momentarily gave way to laughter as Clownthony Kiedis belted out the “first-born unicoooorn” line from the song “Californication.”

She picked up a long lamp with a heavy base just as the bedroom door swung open. Clownthony Kiedis held a megaphone to his mouth.

“Fargo, Minnesota! Man in North Dakota!”

Emily javelined the lamp into Clownthony Kiedis’s face, but it only seemed to energize him. As he headbanged around the room, his pants began to fall off, revealing a naked lower half of his body, save for a knee-high gym sock where his clown anatomy would be. As Clownthony Kiedis moved closer, gyrating his hips and rap-singing banga-langa-booga-bong, Emily managed to pull off the sock to reveal two D-size Energizer Batteries, which she quickly removed.

“Caliiiifoooo…” Clownthony Kiedis’s voice trailed off, dropping an octave or so as his body slumped to the floor.

“Whoa,” said Emily.

She never babysat for the Adamses again.

Rosecrans Baldwin

Both of the producers hold up a hand at the same time. The writer stops midstream, caught off-guard, and rests her hands on the table.

Producer one: “Number one, does it have to be a clown?”

Producer two: “We’ve seen clowns.”

Producer one: “Tell you what. I had this idea just a second ago. How about this, this is great: It’s the babysitter who’s really the one we’re worried about.”

Producer two: “I love it. Forget the clown. The girl’s our villain. The networks are dying for stuff like that. So what’s her superpower?”

Producer one: “Right. What sets her apart from the others?”

Producer two: “Hey, who’s the chick, from Homeland?”

Producer one: “Claire Danes.”

Producer two: “Exactly. She’s what, retarded?”

Producer one: “Not retarded. What do you call it, on the spectrum.”

Producer two: “Alzheimer’s?”

Producer one: “ADHD.”

Producer two: “Asperger’s.”

Producer one: “That’s it.”

Producer two: “And an addict. So none of that, but along those lines. People eat that shit up. Like the girl on The Bridge.”

“If you’re stuck on making the chick the villain, you’ve got to give her a superpower. Like she’s an alien, but on Earth.”

Producer one: “Autistic. Also an addict.”

Producer two: “Or what’s the other, The Killing, that short chick.”

Producer one: “Adopted.”

Producer two: “What we’re saying is, if you’re determined to do this with a girl in the lead, and we’re not saying you should, mind you, it’s a bad move however you cut it, overseas, but if you’re stuck on making the chick the star, you’ve got to give her a superpower. Like she’s an alien, but on Earth.”

Producer one: “A crippled alien fallen to the planet.”

Producer two: “So you make her eat the kids and the dad. But keep her a sexy alien, conceptually. You think Charlize. Or Heather Graham, Heather Graham’s reading a lot right now. But so we can still picture fucking her, is important.”

Producer one: “Look, we’re not writers.”

Producer two: “Yeah. Maybe it doesn’t have to be an alien.”

Producer one: “The point is, give us a world we haven’t seen before.”

Producer two: “Put us in a world where this kind of thing happens, emotionally.”

Producer one: “Look, this was great. This was great! Thank you so much. Make sure you see Jeanine on your way out, she’ll validate your parking.”

Graham T. Beck

But it was already too late. The clown had started his wondrous routine: first the flower that squirts water, then the endless handkerchief in rainbow colors, balloon animals, juggling, a tiny car, pratfalls.

When the parents finally returned home their once-promising children had sworn to become vaudevillians and Emily, poor Emily, had signed on for an internship with Cirque du Soleil.

Jonathan Bell

In a second, a microscopic pulse of adrenaline flushes through Emily’s veins. She feels as though she has plunged her limbs into iced water. She opens her mouth, but there is no sound.

“Emily? Did you hear what I said?”

Her brain transforms the next 10 seconds into a supercut of horror movie cliches, images of terror that she experiences as if she is detached, hovering above her own hunched, petrified body. The clown’s closed eyes snapping open in closeup; the children’s bedrooms daubed in blood; a light flashing bright against a twisting, stabbing blade.

“Emily! Emily—go get the kids! Get them out! Now!”

Finally, the urgency in his voice snaps her back to the present and she looks up, her breath held.

The clown is still there, motionless, eyes shut. She studies it for even the slightest flicker of movement, but between the blue light of the screen and the shadowy corner there is no way of knowing for sure.

“Yes Mr. Emerson, I’m here,” she hears herself saying. Still facing the figure and leaving the TV muted but aglow, she backs slowly out of the room. When she reaches the foot of the stairs she speaks quietly into the receiver.

“You…you want me to get the kids out? But why?”

“Just do as I say. Get them up and get them out. We don’t have much time. I’ll meet you out front.”

She races up the stairs and into Billy’s room. She shakes the older boy awake and tries not to let her panic show as his eyes open slowly and sleepily.

“What is it Emily? Are Mom and Dad back?”

“They’re coming soon. Can you get your little sister? We have to run an errand. Quick. It’ll be fun.”

A shape emerges from the game room, dark, tall, a low wail coming from deep within it. The front door opens, finally.

Billy rouses Claire, shushing the little girl as she climbs noisily out of bed. All the while Emily listens for a footstep on the stairs or the creak of a door.

As the three of them reach the bottom of the stairs there’s a sound from the game room. At first it’s indistinct, then it forms into an inhuman roar that builds and builds and doesn’t seem to stop.

Emily flings herself at the front door and starts undoing the bolts.

“Come on children, follow me…”

A shape emerges from the game room, dark, tall, a low wail coming from deep within it. The front door opens, finally.

Mr. Emerson is standing there on the porch.

“Quick, children, Emily. Outside. Now!”

They run out onto the driveway. Mrs. Emerson is in the passenger seat of the family’s SUV, her face a picture of shock illuminated by the garage light as she looks past them to the hallway.

The shambling figure draws closer, the clown outfit ragged and dirty, the eyes half open, the horrific makeup askew and smudged.

Mr. Emerson draws a deep breath and stands up straight, ready to face it down whatever it takes.

The figure draws closer, raisings its red eyes to meet his.

“Mr. Marvo,” Mr. Emerson begins haltingly, “I’m very sorry. We were under the impression you’d left Claire’s party early. That’s why I hadn’t paid you. Had I known you’d retired to the game room to sleep off the half bottle of whisky you stole from the kitchen, I would have probably called the police.”

The clown grunts.

“I’ll take 20 bucks,” it says, “and I’m sorry about the Scotch.”

“Done,” says Mr. Emerson, “and don’t expect a Yelp review. Now get out of my house.”

Pitchaya Sudbanthad

The call goes dead. Emily turns to the clown statue. It opens its eyes and returns her gaze.

“Mike has always been a reductivist,” says the statue.

“Please don’t hurt us,” says Emily, immediately regretting her use of the plural. If the statue steps toward her, she will scream to wake the children upstairs.

“Hurt you? Why would I do that?” the statue asks.

“Because that’s what self-animating life-sized porcelain figures do?”

“You’re so projecting your own fears onto my anthropomorphic form.”

“Whatever it is, you’re up to no good. That’s all I know.”

“OK, for your information, I have many, many diverse interests. Please do not hem me to any one thing.”

“Well, one second you’re standing there all sinister and the next the call drops and then you’re talking to me. What do you want me to think?”

“You’re trying to turn this around and get me to state my presumptions. Don’t think I don’t see your move there.”

“There are no moves. I’m not trying anything.” She scans what’s nearby. She can grab one of the elephantine bronze bookends. Or she can try to shatter him with the desk bonsai, a dwarf ficus with sad droopy leaves.

“Oh, forget it. Every new moon I come to life, and what do I get? A scared girl or a bored guy who wants to debate economic policy.”

“Are you talking about Mike?”

“Who else? He’s got monetarism written all over him. Couldn’t you see?”

“Every new moon I come to life, and what do I get? A scared girl or a bored guy who wants to debate economic policy.”

“He did mention something about money supply.”

“Yeah, yeah, I’ve heard it like 50 times. Spare me.”

A clattering of feet. The children have woken and come downstairs. Keeping one eye on the statue, she raises a palm to warn them to stay at the door. They ignore her.

“Do you want to play ping pong, Winifred?” Milton, the younger of the two, asks the statue.

“Not tonight, I’m supposed to rest my hernia. Besides, your father doesn’t want me corrupting you with my thoughts on aggregate demand.”

Emily takes advantage of the distraction. She whacks the clown with a crystal decanter from the credenza. The left parts of his made-up face, seemingly tufted by a blue marble-like eye, disintegrate and scatter on the carpet.

“Goddamit,” the clown yells.

“Run, children! Run!” Emily screams. She’s the only one who leaves. The children watch through the window as Emily disappears down the long driveway.

“Are you OK, Winnifred?” asks Margie.

“I’ll be fine. I’ve learned to always carry tubes of superglue.”

“What will we tell father?”

“That he needs babysitters awesome at discretionary decisions, that the growth of his capital has far outpaced that of his brains. Now, will you please help me pick up my face?”

Lauren Daisley

Emily runs from one wing of the house to the next until she has all three kids out the front door, two sprinting on wobbly little bowlegs, the other slipping off her hip no matter how tight she holds him. Once outside, standing in socks on wet leaves at the end of the circular driveway, the kids stare stunned at their house as nothing at all happens to it. Emily calls 911. The cops rush to the house and confirm that nothing at all is happening.

The rest comes out in the local gossip. The father had been keeping a mistress, to whom he had recently confessed his paralyzing fear of clowns. When, soon after, the mother went away on a business trip, the mistress stumbled upon the garish styrofoam statue at a tag sale and slipped it into the house while the father was in the shower after a lunchtime tryst. She thought it would be a laugh. Turns out it was grounds for divorce.

Erik Bryan

“Why?” Emily asked. “What’s the deal?”

“The clown is an illegal immigrant and he’s going to take your babysitting job!” the father responded in what seemed to Emily like all seriousness.

“Uh,” Emily cautiously replied, “I don’t think that—”

“That clown is Benghazi! He’s part of an Obama conspiracy to kill Americans, including you and my children! That clown goes all the way to the top!”

“That clown is the voter fraud of knockout games!” the father yelled.

“Um, are you feeling OK, sir?” Emily asked.

“Go to their bedrooms and smother my children to death or else they’ll have to live in a world where that clown is forced to bake cakes for gay and lesbian race riots! Do it!”

“Cakes for what?” Emily asked, increasingly more exasperated.

“That clown is the voter fraud of knockout games!” the father yelled.

“That’s not a thing,” Emily said flatly.

“That statue of a clown is the Ebola of ISIS.”

“Literally nothing can be the Ebola of ISIS, sir.”

“I really need to you to freak the fuck out right now, Emily,” the father said.

“Your kids are asleep and they’re fine. I’m going to read in another room now,” Emily said before hanging up the phone and turning off the TV.

The statue of the clown remained perfectly immobile, its stare undeniably creepy and unnerving, but ultimately harmless to the general public.

The father, of course, is The Media.