The Window Cleaner

Dirt is difficult to see on glass. That’s why so many people don't bother to hire a professional for the job—they just can’t see what’s wrong.

James cleans windows. He’s been cleaning windows for decades now, and you can see a reflection of each and every one of them etched into his face.

He’s always in the same gear. A pair of good sneakers, pale jeans, a T-shirt. Sometimes a light sweater, but only on chilly mornings. It’s warm work, climbing up and down a ladder all day long. His work takes him to towns across this part of southwest England, around Bath and west Wiltshire. He’s never advertised, every job he ever got came his way via word of mouth. People appreciate clean windows. They tell their friends. He works where the windows are, which is everywhere. We chatted, a few weeks ago, about the weather and about his work.

His method never varies. He knows every house on his round, and he knows every pane of glass. He knows exactly which window will be the last before he breaks for lunch, and which will be the last of the day. He knows every sill and ledge, every awkward corner, and every helpless barking dog.

You see a lot of dogs, he says. So many dogs left on their own while their owners are at work. He feels like he knows some of those dogs better than their owners do. They stop barking after a moment, and regard him at work. Their little wet noses follow his hands as he moves the little wet sponge over the glass. They love having something to do—anything to break the tedium of sleeping all day—so they go nuts when they hear James’ ladder clattering up the driveway or the garden path. He tends to drag it behind him, scraping its lower feet over concrete and asphalt. He never used to do that, not when he started. But it’s been a long time.

Back then he was lucky to get three pounds for a house. Now it’s about 25 or so. It depends how many windows you have. Obviously, it’s in his interest to clean every window as fast as possible, but you can’t rush a professional job. Especially not when you’re proud, as James is, of doing it right. Owners know when he’s been—sometimes, very rarely, they call to say thank you. He can’t remember the last time that happened, but it has happened.

The process is the same for every window. Adjust the ladder and check that it is stable. Ladder safety is second nature now, after so many years. He’s never fallen off, but had one or two narrow escapes. He heard of a man who broke his hip and never cleaned windows again. James has been very careful. He doesn’t want that to happen.

So look up, see where you’re going to climb. Then climb, carefully, don’t rush. Your tools are hanging from your waist. Professional tools, lightweight but sturdy, a good size but not too large to get in your way as you climb. The soaper’s only just wet enough for the window at hand—only lift the liquid you need.

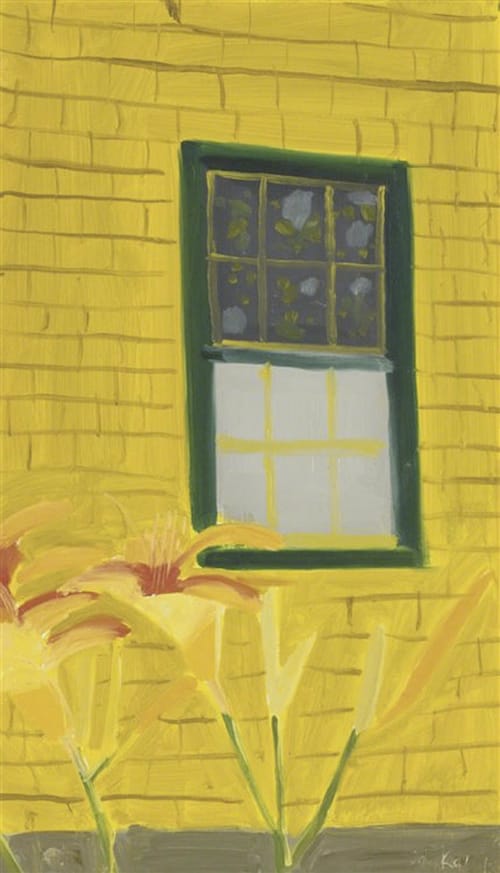

Now for the window. Examine it. Brush away loose dirt and cobwebs, press momentarily on the frame to be sure the window itself is firmly in place. Oh yes, that’s happened before—entire windows have fallen inwards, or sometimes outwards, at the slightest touch. After a while, you learn to spot the houses where it might be a problem. You learn to check. There’s good glass and bad glass. Stay away from bad glass.

Ladder safety is second nature now. He heard of a man who broke his hip and never cleaned windows again.

Now, apply the soap. Weave it across the surface. Cover every part of the glass, right into every corner. Anyone can wash a window, but only professionals like James get it right, get the soap into each corner and clean it away again afterwards. Professionals know when homeowners have been doing their own cleaning. They can see the missed patches, the streaks and marks that got left behind.

After the soap, the wipe. The statement of a window cleaner’s art. It must be smooth enough to be a free-flowing, single movement. James’ right arm can move through it with no effort at all, as if choreographed. The wipe must be firm enough to push the moisture along the rubber blade, removing it from the window surface without leaving behind streak marks. And it must be thorough, reaching to all those corners that most people ignore. A good wipe leaves a visible shine behind it. A transparent mark of professionalism.

Even then, there’s more to do. A window needs buffing for a properly clean finish. It’s hard to see dirt on glass—that’s why so many people never bother to engage a window cleaner, or to clean their own windows. They just can’t see what’s wrong.

But once it’s done, oh, once their windows are clean, what a difference it makes! That’s what they say. That’s wonderful! What a difference! Goodness, I had no idea they were so dirty.

No idea, James mutters into his flask of coffee. He brings it out with him every day. It sits on the passenger seat of his car, next to his lunchbox, which always contains two rounds of sandwiches, an apple, and a chocolate bar. On the back seat is his receipt book and his list of customers. He doesn’t really need the list, because he knows his round. But he keeps it to hand, and diligently ticks off each house as its windows get cleaned. He has a system.

I wonder if James is lonely. He looks lonely.

I ask him what he thinks about as he’s cleaning, but he doesn’t answer directly. You get lost in your thoughts, he says. Best not to dwell on things, mind you. He enjoys being outside. He notices things—birdsong, insects, clouds, the weather, and the seasons. Things the rest of us miss as we bury our noses in our smartphones. His skin is coarse and roughened, but not tanned. When he smiles, which isn’t often, you get the sense that behind the lonely exterior he’s a kind man, someone who enjoys a laugh when there’s a laugh to be had. But he likes to be by himself. He’s happy that way.

James is absorbed in his work, which is meticulous, inch-perfect. As he steps off the ladder and lifts it, ready to climb to the next window, the sun pokes out from behind the clouds and a flash of light reflects off his handiwork. The same light glints off windows all the way down the street. A path James has carved himself, with a sponge and a cloth and a ladder.