Three Thousand Head-Butts

Strong men also play video games. The story of how a young depressed man became a bear, dragon, tiger, and man-wolf.

In high school, if memory serves me well, my life was a large, unchaperoned house party where every heart revealed itself, where every flavor of wine cooler flowed—even Melon Splash. Especially Melon Splash. But something happened between high school and college. My personality powered down and turned inward. Almost overnight, I went from being one of those nerdy white kids who, through his irrepressibly outgoing nature (and countless high-powered nerd contacts), dominates the pages of his high school yearbook, to becoming one of those nerdy white kids who crawls into an army fatigue jacket and Walkman headphones the minute he rolls out of bed, and quietly sketches in the middle of the quad.

For the next three years I fell into existential inertia and moody introspection, broken only by the occasional serendipitous handjob. I developed new, gloomy affectations. I read Important Writers—who died of alcoholism, suicide, and syphilis—and sneered at my philistine classmates for prancing around campus in Top Gun-inspired bomber jackets and behaving like life was anything but a cruel and meaningless puppet show. I slept late, missed classes, and drank steadily from a bottle of liquor I’d secreted in my dorm closet. Yes, it was Kahlúa but I drank that Kahlúa straight, like Charles Bukowski. A gay, Mexican Charles Bukowski.

My roommate, also named Todd, was of a similar demeanor, though his quiet reserve was more intellectual, less tortured. A John Coltrane poster hung above his bed; a Salvador Dalí print and Barton Fink poster hung above mine, to remind passers-by of both the persistence of time and my interest in very esoteric cinema. Most evenings Todd and I read silently side-by-side, or wandered down the hall to play Nintendo. While other students groped each other at weekend keg parties, Todd and I partied in the Student Union game room. There, we’d sink a fortune of quarters into Golden Axe while lonely women nearby played Tetris, and Asian men and women played billiards. My summer and winter breaks were equally anti-social, dominated by daily trips to the video store to rent games for my Sega Genesis, which I preferred to play alone. (I’m not sure what Todd did on his holidays; his life beyond campus was a mystery to me.)

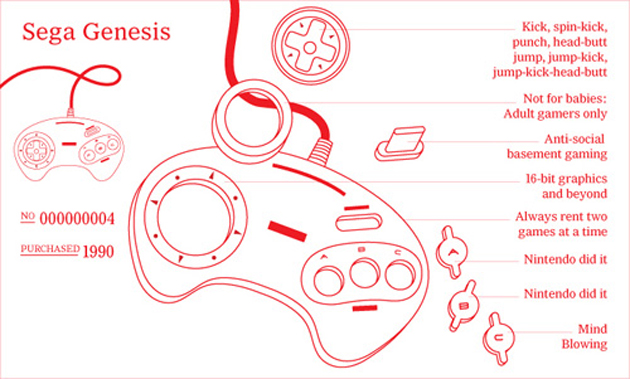

The Sega Genesis was released just a few short years after the Nintendo Entertainment System, and boasted better sound and much-improved graphics. (Its graphics were 16-bit to the NES’s 8-bit. That’s twice as many bits!) The Genesis further distinguished itself as a new kind of video game console for the adult gamer—a pioneering way of marketing what was essentially an expensive toy. I had my first Genesis sighting in a Macy’s department store in the young adults section—where no child would dare to tread.

While the NES was approachably boxy, the Genesis was designed with a black semi-matte casing, contoured like a sports car. It confidently stated, “Hey, I’m not some kind of goddamned baby, you know.” The controller matched the NES’s “A” and “B” buttons, but added an additional mind-blowing “C” button.

Next to Sonic, Nintendo’s Mario lumbered along like some kind of overweight, middle-aged day laborer.

The most striking difference, however, was its in-pack game, included with the purchase of every Sega Genesis. The NES shipped with Super Mario Brothers, in which your protagonist wore overalls, ran from turtles, and leapt from cloud to cloud. The Sega Genesis shipped with a game called Altered Beast, in which your protagonist was a muscular man in a wrestling singlet, with the ability to change (or “alter”) his form into a bear, dragon, tiger, or man-wolf. You then used your supernatural abilities to do what came naturally—namely, punching things in the face. For a launch title, Altered Beast was surprisingly dark and violent—a thudding, paranoid hit of brown acid compared to Super Mario Brothers’ upbeat psychedelia.

I had my first taste of hardcore Genesis action at a friend’s house, and was immediately drawn to another game that came to be emblematic of the console: Sonic the Hedgehog. The game levels in Sonic the Hedgehog were colorful and busy, especially when compared with the muddy and bruise-purple palettes favored by the majority of Genesis titles. And Sonic had something else no other game could match: speed. The action moved incredibly fast—so fast there were moments when my eyes could barely follow. Next to Sonic, Nintendo’s Mario lumbered along like some kind of overweight, middle-aged day laborer.

Over two summers, I rented dozens of games for the Sega Genesis, but remember very few of them. This is partially because I was diagnosably depressed throughout most of college, and partially because most Genesis titles were variations on a trope. As a shirtless barbarian/street tough/ninja/anthropomorphic animal, intractable circumstances compelled you to walk (or temporarily ride a dragon) from left to right on a mostly 2D horizontal plane, while punching, kicking, tossing, slashing, or shooting endless armies of slow-moving and nearly identical thugs attempting to thwart your progress. The fortitude of these enemies was measured by the number of times you were forced to pound them until they finally jumped backwards, hit the ground, flickered a few times, and disappeared like it was the Rapture. Once all the low-level mooks were sent to heaven—and only then—you would be beckoned to proceed forward, where you encountered another wave of jerks.

Occasionally, you could expedite your progress with a crowbar or trash can, or improve your longevity by eating a gigantic apple or hamburger that someone had left in the middle of the street, or inside a wooden crate.

Finally, you would find yourself alone—but not for long! You were thoughtfully alerted that trouble was afoot, often signaled by a darkening of color, some pulse-pounding MIDI music, some building rubble or stalactites breaking loose above you. In the next instant, you were standing face-to-face with a super-ninja/hammer-wielding giant/hydra/heavily armed gunship/mechanized spider four or five times your size. To win, the next several minutes were crucial. All that spin-kicking and head-butting you’d performed to reach the end would need to be repeated—for about five solid minutes, long enough to make any rational gamer question whether he was playing a game or developing a Tourrette’s tic. This familiar course of gameplay applied to nearly all of the 100 or more titles I played, as I jammed cartridge after cartridge into my Sega Genesis like it was some kind of truck-stop lot lizard.

I consumed these games greedily, renting two at a time unless a pretty girl was working at the store—then I’d rent one game plus an esoteric movie, always making sure to ask, “Do you think my little brother would enjoy Battletoads?”

A more self-actualized person might have realized he’d reached his spiritual nadir while speeding home on a Saturday afternoon to play freshly rented copies of Splatterhouse and Chester Cheetah: Too Cool to Fool. Sadly, I was not that person. It turns out many more motorcyclists would need to taste my chain and many more dudes would need to drop-kicked in the face before I was to be shaken from my torpor.