Tilt

A look back to the dot-com boom years when money grew on trees, dreams were cast, and happiness could be delivered via Urbanfetch.

In the late nineties, my generation had a sweet, brief revenge against the Baby Boomer ruling class. For just a few short years we were ungenerously branded “the slacker generation”—often in very scolding tones, and usually accompanied by a dimly lit photograph of a dreadlocked, goateed dude wearing a Pearl Jam T-shirt and slumped low in a recliner. Then someone made the Internet, and suddenly those same twenty-something media punching bags were gracing magazine covers again, now clean-cut and business casual, grinning ecstatically and illuminated by computer monitors, beneath headlines like “YAHOO.CASH,” “GENERATION X-CESSIVELY WEALTHY,” and “IS FLOOZ THE FUTURE OF MONEY? OF COURSE IT IS.”

I was one of those web-capable Patrick Batemans. For the first time in my life, I was wealthy enough to buy nice things—like dry-clean-only sweaters and furniture that actually came pre-assembled. With no experience handling money, or even having money to handle, I quickly developed a “why not?” approach to personal wealth management. The underlying principle was: If a single item’s cost did not exceed $2,000, why not? This made perfect sense to me.

In short succession, I moved into my own apartment, bought my first real stereo—with separate matte black components, because all-in-ones were for girls—then added surround speakers and a DVD player. To command all of my glorious new equipment, I acquired The Most Intimidating Looking Universal Remote In The World. TMILURITW had the approximate dimensions of a Norton’s Anthology of English Literature, and its multitudinous functions were displayed on a wide contextual LCD screen. It required three days of trial and error to program it imperfectly, and even then could be safely operated only by myself or an authorized Sony reseller. Then, with all of my toys wired in, I sat on the edge of my (black, leather) couch and impatiently counted down the days to 9/9/99.

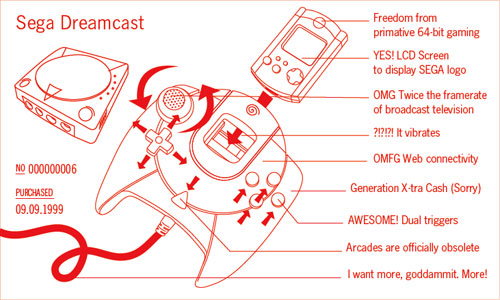

I would not expect a normal, reasonably mature person to understand the historical significance of 9/9/99, but every serious gamer anticipated that stutter of nines with the same fervency Chabad Lubavitch Jews reserve for the Messiah’s coming-out party. September 9th, 1999 was the day the most honorable SEGA corporation would free us all from the tyranny of depressingly primitive 64-bit gaming. Not coincidentally, this was also the launch date of the new SEGA Dreamcast video game system.

I was my own only child. My impulses made me dizzy, like I was hurtling backwards in a time machine, on a mission to high-five the unspoiled 12-year-old version of myself.

On its clean, white surface, the Dreamcast was humble and unassuming. The console was an unadorned plastic square with a slightly rounded top surface that gave it a slight pilsner bloat, perhaps to accommodate the fantastic junk crowded inside. Nintendo 64 was for savages; Dreamcast had 128-bit graphics that could push 600 kerfillion polygons per neutronium, or whatever those ads said. In-game graphics moved at 60 frames per second—that’s twice the framerate of an episode of Airwolf. Plus, online connectivity and a proprietary web browser! Game controllers with dual triggers! A VGA input! Add-on “jump packs” that would make your game controller vibrate whenever your character is killed, just like in real life! And revolutionary new memory cards with built-in LCD screens that allowed you to display extra stuff, like the SEGA logo. (And rarely anything else.)

Even those not crippled by their own grotesque impulsiveness would have had difficulty withstanding the tidal wave of hype SEGA generated for the Dreamcast. It was the first game system launch that had the added media muscle of the web, and in the months prior to launch, everywhere you clicked there was the easy-to-recall street date and the Dreamcast’s appropriately hypnotic, swirling, red logo—it looked like the endless curlicue that kicked off games of M.A.S.H. Every advertisement was cleverly punctuated with the tagline, “It’s Thinking.” I was nice to know someone would finally be doing the thinking in my home.

I took a sick day on 9/9/99, and I was surely not alone. In fact, I expect new media more or less came to a screeching halt that day, as if beset upon by a mysterious wealthy nerd epidemic, leaving managers to wonder, “My God, who will Q.A. this very important Chips Ahoy-branded Shockwave Game?” When the FedEx guy arrived at the apartment around 2 p.m. with my Amazon.com pre-order, I shook like a junkie as I tried to sign my name on his Etch-A-Sketch. Once I was finally alone, I split the packing tape with a house key; peeled back the box flaps, savoring every grueling second; slowly denuded the Dreamcast from its Styrofoam casing; then spent the next four hours having the most intense optical intercourse of my life.

The Dreamcast was worlds beyond what I had grown accustomed to in home-video-game systems. It was the first time I can recall playing a game and thinking, “I shall never love another.” It officially made arcade video games obsolete. The colors were bold, and the lines were clean—characters no longer appeared as if they were fabricated from corrugated cardboard. Like the majority of people who purchased a Dreamcast on its launch day, my first game was the swords-whips-poles-and-fists fighter, Soul Calibur. This game was often featured in commercials for the system, as a kind of technical brag, and after spending just a few minutes flailing ineptly on Soul Calibur’s stage of victory, I honestly think my eyes came.

Given that experience, my first reaction to the Dreamcast should have been, “Thank you, SEGA. Your work here is done.” Unfortunately, I was so far gone by this point that my response was slightly more abrasive: “More, Goddamnit. MORE!” After all, I was living in a magical time when my disposable income was great and my parental supervision was severely lacking. It was like I was my own only child. My impulses made me feel dizzy, like I was mentally hurtling backwards in a time machine, on a mission to high-five the reasonably unspoiled 12-year-old version of myself. Together, we were going to live the life we only dreamed of, back when I watched Silver Spoons with envious eyes.

Teaching four-letter words to a Japanese man-fish living in your television is what recovering addicts usually refer to as the moment immediately preceding total clarity.

And that’s probably the fantasy I had in my brain when I left my apartment for the first time that day, my eyes red and caked with their own semen, and power-walked to the Gamestop in my neighborhood where, within five hours of purchasing my first Dreamcast game, I purchased my second one. And the one that whispered in my ear, suggesting maybe now was a good time to get the old video game club back together, with a slightly more restricted membership—i.e. no fedoras. (Well, OK, one fedora.) It is also the fantasy that wormed its way back into my brain when I rationalized investing in a plastic light gun, to play The House of the Dead 2, a violent zombie shooter notable both for its generous splatter and its inclusion of the worst voice acting in the history of gaming—the actors were so dramatically wooden they wouldn’t have made callbacks on a snuff film.

At a certain point, my time-traveling revenge plot must have accidentally fused to my brainstem, like an arachnoid cyst. How else can I explain my purchase of a massive, unwieldy arcade stick, designed to look and feel like it’d been ripped off a classic arcade cabinet? Or Seaman, a freakshow of a game that included a microphone which players would use to teach language to a virtual fish? More specifically, a virtual fish with the face of an uptight Japanese businessman, to whom I repeated the word “shit” for several minutes each day, until he finally mimicked the expletive in accordance with my exacting demands. (Two weeks later, I accidentally killed Seaman-san, due to not understanding how to virtually feed him his virtual food. Sadly, the game did not include a virtual toilet for disposing of his virtual remains.)

Teaching four-letter words to a hideous Japanese man-fish living in your television set is what recovering addicts usually refer to as the moment immediately preceding total clarity. Unfortunately, I was not as cogent or self-aware as the average chronic substance abuser.

The closest I came to clarity or reason—honestly—was when the PlayStation 2 and Nintendo Gamecube arrived about a year following the Dreamcast. Although I was a modest fan of the first Playstation, the Playstation 2’s high price tag and weak lineup of launch titles was somehow offensive to me. Besides, I was still incredibly happy (not satisfied, but happy) with the Dreamcast’s weird and original games, like the graffiti-and-inline-skating title, Jet Set Radio; the ADD-paced brawler, PowerStone; or Space Channel 5, which featured a female newscaster named Ulala who was ordered by aliens to dance, but would also sometimes shoot them. (Or kiss them, I don’t remember.)

Eventually, my shame outweighed my sense of entitlement, and I became a real drag.

I championed my own arbitrary opinion, telling friends I would never buy a Playstation 2 as a matter of principle. So instead, I bought a Gamecube. Then, six months later, I sold the Gamecube and bought a Playstation 2. And a Nintendo Gameboy. And also a Gameboy Advance, which I eventually donated as a Christmas present to an underprivileged child, through an organization called Operation Santa. Feeling good about that act of charity, I rewarded myself with a PSOne, a slightly smaller, more portable version of the original Playstation system. (I also exchanged the PSOne later, for more PlayStation 2 video games because, let’s face it, the Dreamcast was so 1999.)

In no time at all, my apartment was filled with egregiously uninformed purchases, like a vintage Ford stand-up gumball machine, orange inflatable rocket ship, signed-and-numbered Shepard Fairey prints, and a short-lived wireless device called MOJO that was heralded as a dynamic nightlife guide but updated so infrequently it ended up being a plastic box that displayed last week’s film listings. I’d over-complicated my life, which made me wistful about the more uncluttered childhood I had been working so hard to avenge—one where a Radio Shack TV Scoreboard and its 1-bit graphics were enough. My value system had been displaced so far from its axis that I was unconsciously consuming my own nostalgia—scouring eBay for vintage gaming consoles, and accruing more to restore a sense of having less. I’m sure my therapist would have had something to say about that, if I hadn’t been too embarrassed to share with her the existential crises associated with owning a plastic light gun.

Eventually, my shame outweighed my sense of entitlement, and I became a real drag. I had this very clear idea of restraint, but had difficulty practicing it, so I just resorted to loathing both my generation and myself. We (I) had too much money, and too much youth. I lost friends because I no longer fit into their increasingly posh lifestyles, or because they were tired of hearing me apologize for my own. What I didn’t realize until very recently was, with guilt and shame hanging over my every decision, my adult life was actually starting to look a lot like my childhood. Then, almost exactly two years after the launch of the Dreamcast, the dot-com bubble finally burst, work dried up along with my savings and, in a blink, my lifestyle shifted from extravagant back to being simple again. Terrifyingly simple.