Window Shopping

Never mind all that gloomy talk of falling real-estate prices. For many renters, even a heavily mortgaged apartment is the stuff of daydreams.

An old-style yellow cab pulls up to Tiffany & Co. as a clarinet somewhere tongues the melody from “Moon River.” It’s early morning and Fifth Avenue is deserted. An impeccably dressed young woman emerges from the taxi and makes her way to the window display where she takes out a pastry and coffee from a brown paper bag and begins to nibble. We watch as she moves from window to window, surveying the contents, occasionally forgetting to eat her breakfast. While we cannot quite make out what she sees, we know these windows contain everything she wants in life and the life she wants. When she has seen what each window has to offer, she throws what remains of her bargain breakfast into a trashcan and walks off down the street. The day and the story begin.

Should anyone ever choose to remake and bastardize Breakfast at Tiffany’s, I propose an opening sequence re-imagined to reflect more contemporary preoccupations. The revised opening scene should be filmed against the backdrop of an early evening in Brooklyn. The throngs of suits coming home from their nine to five grinds in Manhattan would be emerging from the subway stairwells like ants from an anthill, rushing off down various streets towards their various homes and families and dinners. All except for the would-be protagonist who, as the crowd rushes past her, makes her way to the closed-for-the-night real-estate storefront opposite the subway station. Somewhere, “Moon River” might still be playing, as if it had never stopped. Disheveled, lugging her purse and gym bag, she pauses for a number of minutes to read listings she has already read, and which she committed to memory weeks ago: a studio on Pineapple Street; a loft on Gold Street; a townhouse on Argyle Street; a two-bedroom coop on First Place; a one-bedroom condo on Carlton Avenue; a brownstone on Henry Street. It’s fall and the leaves blow in eddies on the sidewalk. She gets cold and turns away from the window to walk off down the street just as dusk begins to arrive in earnest. The occasional “For Sale” sign swings on its hinges, and the story of the day ends only to begin again in the morning.

Every evening I emerge from the subway and stop to daydream about the places I could be returning to—apartments with big windows on tree-lined streets, with crown moldings, 16-foot ceilings—in some other version of reality.

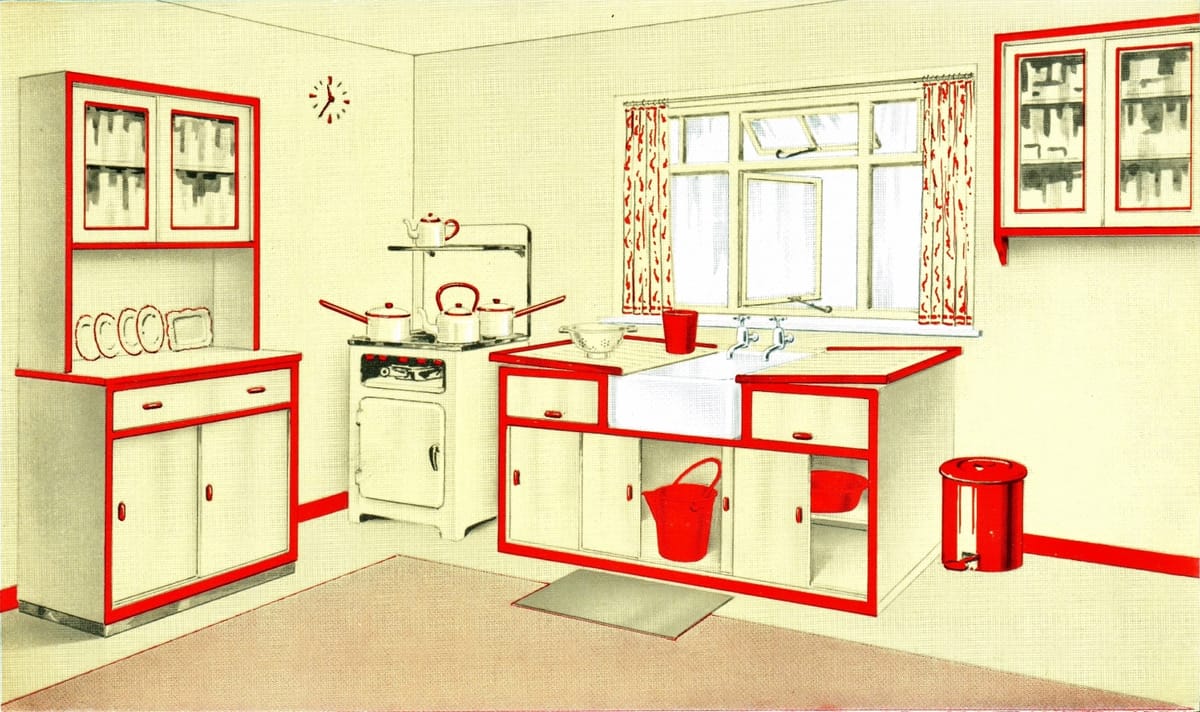

On days when the weather cooperates, this is my routine. Every evening I emerge from the subway station and stop to daydream about the places I could be returning to that night—apartments with big windows on tree-lined streets, with crown moldings, 16-foot ceilings, wide-planked wood floors, exposed beams, updated appliances, and good lighting—in some other version of reality. The routine is not mine alone. I often watch others stop to look. We stoppers and lookers are all on slightly different schedules, unconsciously coordinating our routines so that as one of us is stopping to look, another is moving on, not wanting to crowd the newcomer and his or her quality time with the storefront. This kind of window-shopping is a solitary activity, a conversation among oneself and alternate, imagined versions of oneself, all of whom contribute to the conversation from their comfortable perches in a would-be home. In the upper right-hand corner is where the version of you that went to business school instead of art school lives: Honey, it was a tough decision, B-School You says to Actual You, but it got me this sweet loft and this couch I’m sitting on from ABC Home. I threw out my last Ikea item last month. The center advertisement is the home of that version of you who went out one night despite being tempted to stay in, the version of you that—at that loud, smoky bar—met your future husband as you two bonded over how you both had wanted to stay in that night. Coulda, shoulda, woulda, Married and Domesticated You says to Actual You.

Sometimes I’ll overlap with someone—walking up before he is ready to walk away or vice versa—and in these cases instead of rereading the listings, I’ll look at the reflection of the person beside me, the tilt of his head and the squint of his eyes as he peers through the glass. “What can he afford?” I wonder. “And can he really afford that?” “Is he browsing or really looking?” “What does he want?” “Why does he want it?” When he turns to walk on, my eyes readjust to the words behind the windowpane: “This single-family stunner is the one you’ve been waiting for…”

Whether at Tiffany’s, Barney’s, or a pet store window, at least one or two window-shoppers can always be found entertaining ideas of what their lives would be like if they could afford that necklace, that pair of boots, or that Yorkshire terrier puppy playing adorably amidst shredded newsprint with that pug puppy. The real-estate window-shopping game is different, higher-stakes. The displays are interactive. They require reading and visualization, not just of the unpictured rooms described, but of the lives that could be lived within them.

We’d move again, this time to a two-bedroom co-op in a limestone building in the South Slope with Victorian details, elegantly modernized. For this we would pay $550,000. We would still be attracted to each other.

It would all begin for me with the parlor-floor studio in a brownstone on South Portland Avenue. The one with the marble fireplace, the floor-to-ceiling windows and garden view, and the new kitchen that’s listed for $299,000 but which, if I were lucky and in this market I could maybe get for $279,000. I would have a cat and just a few pieces of functional but beautiful furniture. Occasionally, my writing would get published, but I would be happy at my desk job. I would bring boyfriends home and one day one of these boyfriends would stick and he would move in. My parents would not age and his parents would not get sick. Between the two of us, my cat and his dog, life would be cramped and after nine months or so of living on top of each other I would make the difficult decision to sell so that we could pool our resources and buy a place together. This would not put a strain on our relationship and after looking for months we would decide on a 1.5 bedroom on Nelson Street in Carroll Gardens for $445,000. We would be happy here for a number of years. I’d get a small advance for a book of essays and have discovered my talent for pastry baking; he’d find work with an architectural firm that was young, but getting good press from places like Dwell. We’d get married, succeed some more, and I’d eventually get pregnant with no problem at all even though I would be pushing 35 and I would not gain any unnecessary weight during those nine months. We’d have to move again, this time to a two-bedroom co-op in a limestone building in the South Slope with Victorian details, elegantly modernized. For this we would pay $550,000. We would still be attracted to each other. My little book of essays would have sold well by then and I’d have a contract for another; he would have made partner and be gaining a reputation for his brilliant manipulation of spaces. Neither he nor I would ever get fired or laid off. I would learn how to play the piano. He would build our bed in a woodworking class. Our child would be above average. A few more years and another above average child down the line, my essays would have been turned into a quality television show starring Michelle Williams as me, and he would have just gotten a commission from the city to design a major municipal building. We would again need more room, moving this time into a three-bedroom condo in a brownstone on a landmark block in Park Slope for which we would pay $880,000. Our parents would be healthy and attentive to our children, and sensitive—when the time came—to our relative lack of extra space and thus accepting of the assisted-living arrangements we would make for them. We would be there until the kids were in their early teens. The kids would like us so much they would not feel compelled to rebel and we would all have good skin. We would tell the kids that if they were going to drink they should do it at our house, under our watchful eyes, and the kids would agree and obey. There would be no grisly car accidents in the index of our life, or cancer either. I would have started a side business designing decorative blankets and Brooklyn boutiques would be snatching them up. Because we had always wanted a house to ourselves and because (since we would have invested wisely) we could finally afford it, we would move for the last time into a four-bedroom townhouse on Clermont Avenue. We would pay $1.65 million and consider it a steal. We would host holidays and there would always be room for out-of-town guests. After so many years, we would be getting old, but we would be happy. Aging, death, dying: these are all things we would have, by then, come to terms with years ago.

Of course, the dream and the life both depend on my ability to afford that studio on South Portland in the first place. I can stand for as long as I want in front of that Corcoran window wondering if it would be possible to offer $250,000 for an apartment priced at $300,000. Imaginary bidding does not increase the likelihood of my being able to afford the place.

Precisely because it is such a convenient receptacle for our hopes and dreams, real estate, like baseball, is a national pastime. The American obsession with property and land is as old as the country itself; its most recent symptoms have included, but not been limited to, television channels devoted to home décor, house hunting, and renovations, magazines and websites devoted to the same, and a housing bubble that finally popped and tanked the economy. New York, in particular, is famous for its real-estate fetish. You can’t walk five blocks in many parts of the city without passing a real-estate office and New Yorkers are notorious for shamelessly asking one another how much they pay—or paid—for their permanent accommodations.

In every city, town, or county I visit, I pick up and pore over the real-estate listings; I pedal the stationary bike at the YMCA while watching HGTV; I troll Craigslist apartment listings for fun.

Even in such a city in a country obsessed with all things property-valued, my fascination falls on the extreme end, especially considering that for the foreseeable future real estate will remain, for me, a spectator sport. In every city, town, or county I visit, I pick up and pore over the real-estate listings; I pedal the stationary bike at the YMCA while watching HGTV; I troll Craigslist apartment listings for fun; I have a neighborhood stroll tailored to take me past the houses I covet most: the little cream-colored brick townhouse with the turquoise trim on Adelphi Street around the corner from that tapas restaurant; the brick apartment building on Lafayette with the unusual ironwork windows; the clapboard townhouse on South Oxford; the carriage house on Hall Street across from the Pratt University campus. My favorite section of the Sunday Times is the real-estate section because even though I have no reason to care about what’s for sale in Darien, Conn., I do. I have an application for my iPhone that allows me to search real-estate listings in the vicinity of any place I may be at any given time.

It’s a pastime I have enjoyed for as long as I can remember. As a child, few things delighted me more than looking at a Monopoly board and seeing my houses dotting its properties. In the first grade I could not get enough of a fortune-telling game called MRS PIE. The game was a series of blanks corresponding to different aspects of one’s future life—husband, job, pets, car, number of children—which one would name, for example, four prospective husbands (in my case often including the slightly naughty Abe Costanza) who would eventually be eliminated eenie-meenie-minie-moe style, until each category had been whittled down to one option and the future had been decided. Sometimes the game got specific enough to include such facts as what state one would live in, what flowers would be grown in one’s garden, and how much one would earn. At the center of the game was the acronym MRS PIE, which stood for the first letters of the kind of house in which you would eventually live: Mansion, Ranch, Shack, Palace, Igloo, Estate. Squeals of hilarity would erupt when the game forecast a future that included marrying Abe Costanza, living in an igloo, working as a professional horseback rider in Alabama and earning $2 a year.

Yet while all else could be shrugged off, after each round of MRS PIE there remained the persistent hope that one would indeed end up marrying Abe Costanza and the nagging fear that one would end up cooking dinner for him in an igloo. But worse than an igloo was a shack. The possibility of an igloo was funny; the possibility of a shack was just scary. In a shack there were mice and cockroaches and dust on the canned goods. At least in an igloo you were cooking fresh fish and the climate would be inhospitable to cockroaches.

I am now at an age by which, as a six-year-old, I thought I would be long established in my estate with Abe Costanza. Instead, I am single, only partially employed, and live with roommates in a house next to the Brooklyn Queens Expressway that has been known to shelter a mouse or two, as well as the occasional rat. The house has its charms (tin ceilings, wide-planked wood floors) and I love my roommates, but Abe Costanza and the estate are as far away to me now, pushing 30, as they were when I was busy playing MRS PIE.

I moved with my two roommates—old friends from college—into our house by the BQE just over a year ago. I found the place on Craigslist after only a week and a half of serious hunting, and it looked to be the consummate find. It was a full three-story townhouse only a block and a half away from my older, smaller and more expensive apartment in a desirable neighborhood. It has a backyard, a large living/kitchen area, three sizable, private bedrooms, crown moldings, one working fireplace and one working woodstove, built-in bookcases, and the aforementioned tin ceilings and wide-planked wood floors throughout, all for the bargain price of $2,700/month. The only drawbacks are that it is just one house removed from the highway, so the sound of traffic is a constant reminder of the pace of life. Residue from the exhaust fumes clouds—and eventually cakes—the windows, and the foundations shake whenever a truck passes. Before signing the contract, the three of us had conferred and agreed that these were drawbacks we could live with given the house’s other decided advantages.

We moved in a month later and made the place our own, putting our books in the built-in bookshelves, hanging our paintings on the walls, artfully arranging our knickknacks (an abalone shell, some old-fashioned seltzer bottles, some dried flowers) along the mantle above the woodstove. The place was warm and cozy and we all got along well with it. The sound of the highway faded to white noise. The woodstove was a fun toy on Thanksgiving. The exhaust-clouded windows just made the place seem more cocoon-like.

The place was warm and cozy and we all got along well with it. The woodstove was a fun toy on Thanksgiving. The exhaust-clouded windows just made the place seem more cocoon-like.

The following summer, one roommate made summer plans with her increasingly serious boyfriend, the other returned to her hometown of Seattle to await the birth of her first nephew, and I decided to return myself to my home state of Virginia for a couple of months. We rented the place out to subletters through August. At the end of the summer three of us returned—me, my roommate and her serious boyfriend—while our third roommate, who had been laid off in May, made the decision to stay on the West Coast a while longer to sort out her life. We found another subletter. Life at home was different than it had been the year before and in flux. It was a foregone conclusion that my one roommate would soon be moving in with her boyfriend; it was unclear whether my other roommate would ever be returning. The subletter came and went as a stranger.

One night in early October, after lingering a good ten minutes outside the window of the Corcoran office, I found myself walking down my street towards home noticing only the trash blowing around me and the sounds of the highway getting louder and louder the closer I came to my front door. The street seemed dirtier, the roughage on the struggling trees more paltry, the deserted construction sites and empty lots more ominous and threatening than they ever had before. For the first time since moving in I was recognizably unhappy about going home. I was not going where I wanted to be going.

Hours later, lying in bed, listening to the cars pass, my body was keenly aware of the bed shaking beneath me and the house, in turn, shaking beneath my bed. The quaking seemed a metaphor for my entire life: almost 30 years old with a trembling construction.

Given the dismal employment climate at the moment, the most consistent career advice I’ve been getting lately is to set up as many informational interviews as possible. That way, my older and wiser friends explain, when a job opens up, you will not just be a resume on a desk, but rather a resume with a face. On my walks through my neighborhood and past my favorite houses I often consider what would happen if I went up to the front door of one of these houses, knocked and inquired as to the possibility of setting up an informational interview with the owner of the property in order to find out just how he or she created the life that afforded them that particular home. (When I was a child, I hatched a plan that involved bringing flowers to the owner of my favorite house in Charlottesville and us becoming best friends, a plan my mother made certain never came to fruition.)

The first door I would knock on would be the little cream-colored brick town house with the turquoise trim on Adelphi Street around the corner from the tapas restaurant. It has a crayon drawing that says, “Go Obama” taped to the window so that the picture faces the street. Perhaps the woman who answered the door would be the owner after whom I was inquiring. If that happened to be the case, she would certainly be wondering what this woman (me) could possibly want to talk to her about. She might be wary I had come to claim her adopted child as my birth child, or to assert she was my long-lost sister, or to introduce myself as her new and overbearing neighbor, or to in some other unexpected way disrupt her life. She would hesitate before owning up to her ownership of the house and would not open the door all the way. A child’s voice saying, “Mommy, who’s that?” could be heard coming from inside. Maybe she would then shut the door on me and I would have to walk on down the street a bit to a try my luck at an informational interview at some other front door. On the other hand, maybe she would size me up, decide from looking at me that I was harmless, and give me her secondary email address, offering to have coffee with me in a public place in a few days.

When we met, I would treat her to that coffee and introduce myself properly. I would tell her a little bit about myself: 29, originally from Virginia, well-traveled, well-educated, single, background in media and publishing, dog lover, recently completed classwork for a degree in creative writing, in debt, just now recognizing that I want—and want soon—certain conventional things that a year ago I hadn’t thought I would want for quite some time yet: a well-paying job, health-insurance, a 401-K, a car, a respectable bank balance, a house, a mortgage, a husband, children, a life that has an engine outside of myself propelling it forward.

“You seem to have these things,” I would say in a businesslike manner, looking at her across the table and maybe noticing that she couldn’t be more than seven or eight years older than myself. “Can you just tell me how you got there?”

“Well,” I can imagine her stuttering, “It’s not that easy…”

I might then notice the gray hairs around her temples, the small scar at the base of her neck, the worry lines on her forehead, the absence of a wedding ring, or the dark circles under her eyes. That, or she might also just smile and say, “I’ve been very lucky. I met my husband in college and my father patented the material now used in the brake pads of airplanes.”

But I would never knock on that door and if I did, the woman would not accept my invitation. What might serve me better on these walks is to look not just for those houses I love, but for other things, too. What might serve me better would be to just keep looking even after I’ve seen what I came to see. That’s what I try to do tonight.

It’s the time of day to read the signs that say, “It’s the law: Clean up after your dog.” I start out the way I always do, in the direction I always go, the length of each stoplight memorized, measures of rest in a symphony. Straight down Adelphi, past Myrtle and Willoughby to Dekalb and over to Lafayette. A man in a black cap offers me an illustrated brochure about The Bible as a deliveryman passes on his bike, someone’s dinner swinging from the handlebars. Jay-Z says something from the open windows of a Mazda sedan; I zip my vest and tuck my mouth into my scarf. Kids shoot baskets, the sound of sweet spots on the tarmac and friendly competition echoes down the block. One kid wears a T-shirt that says, “I (heart) My Money.” I pass the last house on that block in disrepair. A right on Lafayette then down and onto South Portland before taking a right again on to Dekalb. People on their way home check their voicemails for special requests and stop at the supermarket to pick those special requests up for dinner. I walk into the park. Someone has forgotten a baseball in the mulch and someone else has scratched the words, “This is the end” into the dirt. A blackbird buries his head in the soft ground and comes up empty, shakes his head, tries again. Out onto Cumberland and over again to Lafayette, then Fulton. The smell of cement and construction, a plastic bag hanging from the branches of a tree stuck in winter, “Pepperoni?” asks a Brooklyn accent as a door swings open and shut. Two women stand in front of an open car door. As the head of one emerges from the collar of a red sweater, they kiss. The last sun of the day hits a mansard roof: the bricks are warm but far away. Lights are starting to come on. A waiter smokes his last cigarette before the dinner rush, headlights turn corners, interiors become visible. There, a pair of collared shirts works late, gesturing at the computer screen. There, a crystal chandelier hangs from crumbling crown molding. There, a woman drops her cardigan over the back of a plush armchair and disappears into a darker room.