After

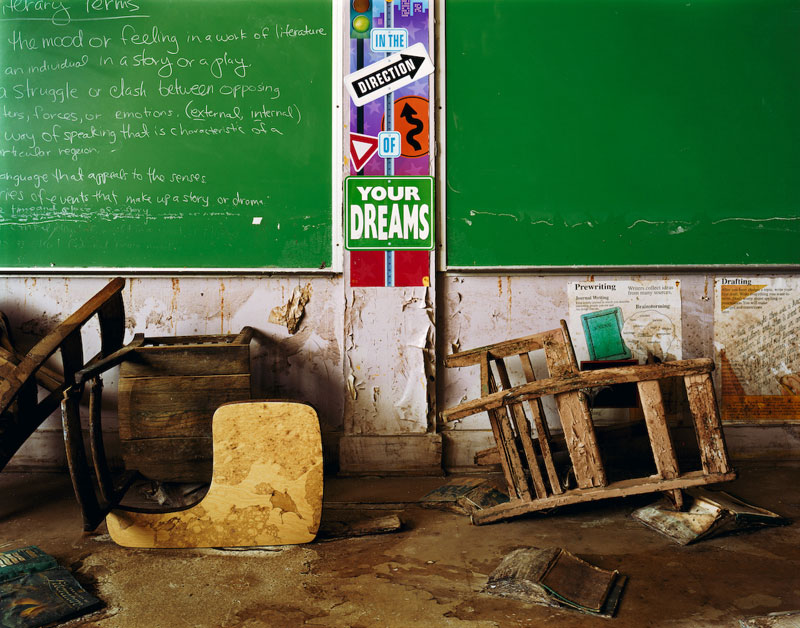

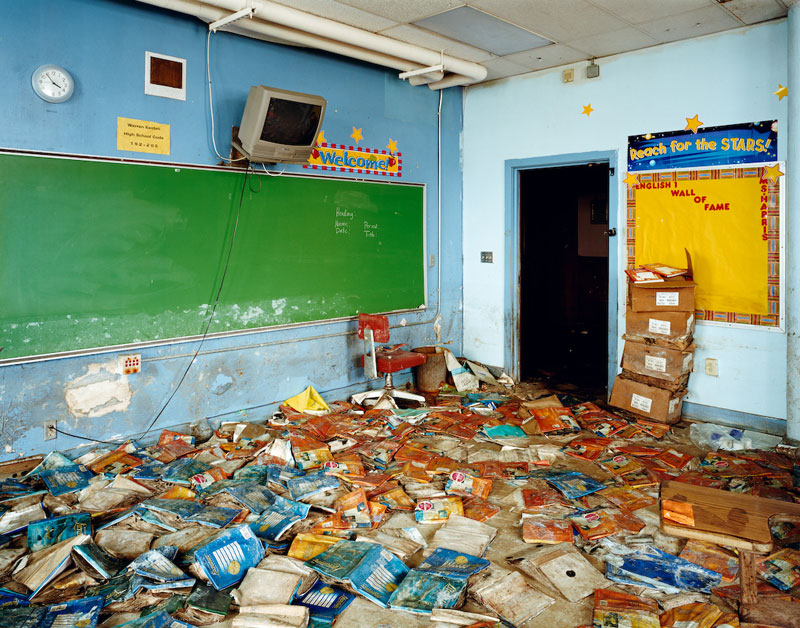

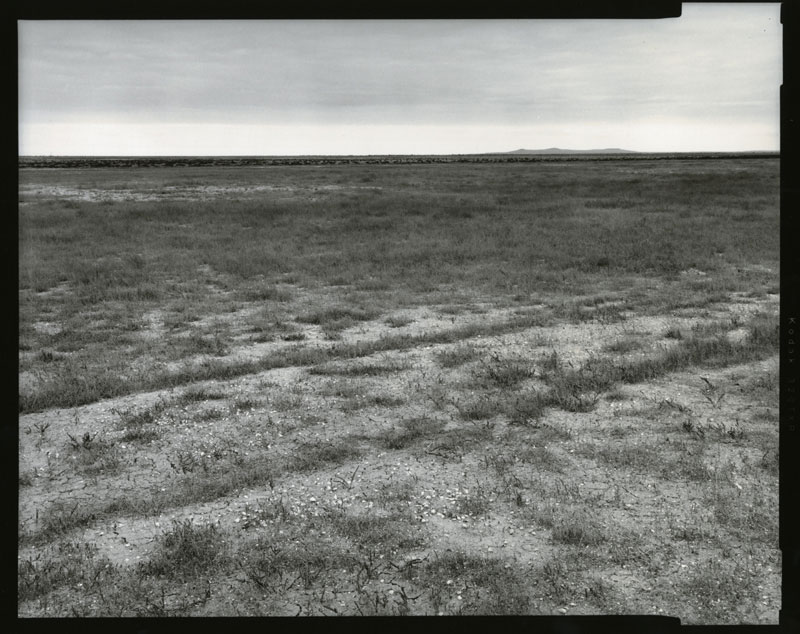

The disappearance of the Aral Sea in Kazakhstan and the flood and evacuation in New Orleans are the tragic results of natural disaster and government mismanagement. These photos tenderly expose not only the extent of the disasters, but our ineptitude and negligence in their aftermaths.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

Can photos bring us closer to these events and aftermaths? Or do the images, orphaned from actual catastrophe, further divide those who lived through disaster from those who have seen it only in pictures? The photographs of Wyatt Gallery and Radek Skrivanek bear witness to nature’s retaliations. Read the interview ↓

The photos seen here are now showing at PEER Gallery in New York. All images courtesy PEER Gallery, all images copyright © Wyatt Gallery and Radek Skrivanek, all rights reserved.

Artist interview

The Morning News: Why did these disastrous events occur?

Wyatt Gallery: Mainly because of nature. Deeper than that, because of man disturbing nature. [We were] trying to control our environment and these are some of the negative effects that come from that.

Radek Skrivanek: The Aral Sea is technically a lake, a large body of water comparable in size to Lake Superior. It is completely landlocked in the midst of the Asian continent. There is strong evidence that the Aral Sea has not always existed there and that its water levels fluctuated throughout prehistory and antiquity. Geological and other forces of nature played a part in this process over many millennia. The present recession of the sea is caused by man alone and [happened] in just a few decades.

The Morning News: What causes a lake to dry up in a few decades?

Radek Skrivanek: It is a complex problem and no single event or person is responsible. It all started, as many other enterprises do, with good intentions: to create jobs, provide income, to put bread on the table of fellow citizens, to use the available natural resources for some visible benefit.

The Morning News: How is it that good intentions can wreak this much havoc on nature and the environment?

Radek Skrivanek: Water from the Aral Sea is supplied by two major rivers of this region, the Amudarya and the Syrdarya. These two rivers were heavily tapped for water to supply the irrigation schemes that were to turn Central Asia into an agricultural giant, feeding and clothing the Soviet empire. The growing demand for water had strangled the sea’s water supply. In fact, the Amudarya, for the most part, no longer reaches the sea. In the height of the irrigation season, the Syrdarya, near its delta, is said to flow backwards. In addition to the agricultural use of the water, upstream countries are using the water to generate electricity to fuel their economies. Cascades of dams are collecting the water from the summer thaw, holding it until the winter when electricity is most needed and releasing it well before the growing season starts in the downstream countries. The breakup of the Soviet Union actually further complicated the situation because as the central authority disintegrated, five independent states struggled to survive and to rebuild their shattered economies.

The Morning News: How are do you understand or characterize the aftermath of the disasters you’ve both photographed?

Wyatt Gallery: I don’t understand it. That’s the main reason why I started photographing it. The [2004 Indian Ocean] tsunami was the first occurrence in my adult lifetime that I could not begin to grasp, at all. It forced me to be involved, and to go and photograph it in order to try to grasp it and understand the severity of it. In New Orleans, I was never able to fully grasp the severity of the impact of Katrina. Everyday that I ventured out to photograph a new neighborhood or one that I had visited before, it was like the first time seeing the disaster. I never got used to it. I never could fathom how high the level of destruction was, and is.

The Morning News: How was New Orleans after Katrina different from photographing the aftermath of the tsunami?

Wyatt Gallery: The major difference was that in New Orleans there were no people, besides the Army. In Sri Lanka the people could not evacuate anywhere, so they were forced to live in tents where their homes once stood. So they became the remnants. Both locations seemed equally fucked in different ways. Katrina seemed endless. But I only saw the impact of the tsunami on one country, Sri Lanka. But just to compare the two, there is a photo of the interior of a train that was knocked over during the tsunami. More people died in this train alone than did from Hurricane Katrina.

The Morning News: Why are the efforts towards rebirth of these areas so inadequate?

Radek Skrivanek: Pertaining to the Aral Sea, I don’t think that rebirth is something that is happening at all. The cultivation of cotton and rice continues and new dams are constructed upstream. In the southern region of the former sea, oil reserves have been found and are currently being exploited, which pretty much kills any real attempt for reviving the sea. Most of the conservation efforts are limited to the flooding of areas near populated centers in an attempt to moderate the local climate. A much publicized effort in the northern region of the sea may result in the creation of a lake perhaps 1/8 the size of the former sea, with questionable ability to sustain the native species of fish.

Wyatt Gallery: I have no idea. But as Americans, we don’t really care. If we don’t see it every day, we don’t even know it exists. And we move on within months. No one cares what is going on in New Orleans now, let alone Sri Lanka.

The Morning News: I notice that there are no people in these photographs.

Wyatt Gallery: There are people in the photos, just not physically. A portrait of them is given through their personal spaces and belongings. The city was abandoned; these items we see in the personal spaces were now the lone inhabitants. They shed light on the lives of the people who once lived there. Through these belongings and sites we can begin to relate to the people who lost their lives as they knew it. Through a Bible in a church, or a quilt on a bed, the viewer is able to connect through similar objects and begin to understand what it must feel like to lose everything you own.

Radek Skrivanek: The people are obviously an essential part of this story. It is people who have created the problem in the first place and it is people who are suffering and will suffer the consequences well into the future. Although I have photographed many people as part of this project, it was a curatorial decision (not my own) to exclude them from the selections for the show.

The Morning News: In what ways has the loss of the Aral Sea affected people’s lives?

Radek Skrivanek: The obvious and immediate losses were the complete disintegration of industries that thrived from the sea such as fishing, shipping, canneries, etc., together with income for the people who lived on the former shores of the sea. However, the more profound losses may be the change in climate caused by the absence of the sea, which used to cool the local climate during summers and keep temperatures mild in the winter. Now both seasons are longer, with more extreme temperatures, threatening the cultivation of the very crops that caused the problem in the first place. Another potentially catastrophic aspect of the desertification of the Aral Sea is that agricultural fertilizers and defoliants that were washed into the sea over the many decades of intensive agriculture in the Aral Sea basin and watershed are now left behind by the receding sea. Together with salt, they are stirred up into the air by wind. [This creates] toxic dust storms that are driven through the region and pose serious health hazards for the population and contaminate the soil regionally.

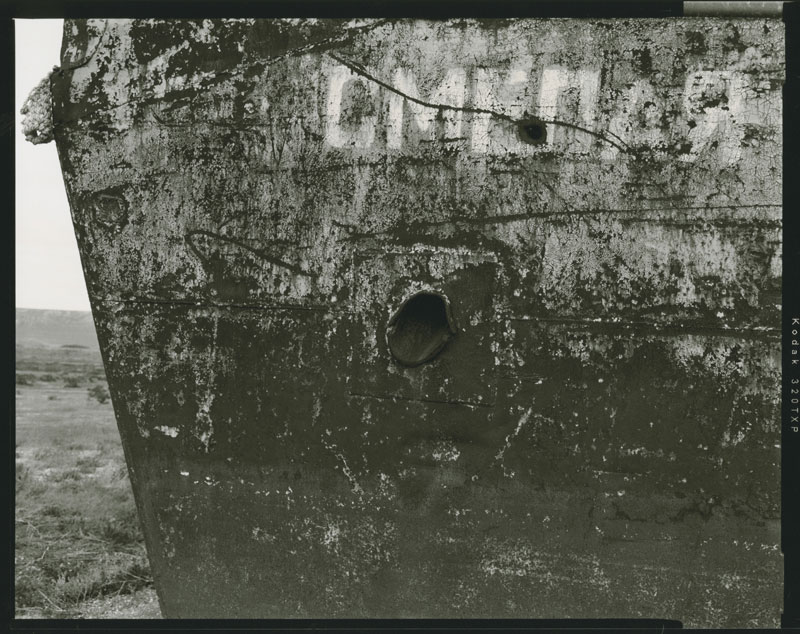

The Morning News: It’s unbelievable that these freestanding, lonesome ships are still here.

Radek Skrivanek: They are relics of the past, representing a bygone era. Their names (Gagarin, Alexey, Leonov, etc.) reflect the pride of a nation [or] empire that no longer exists. There is no one left who remembers those days. Most people who worked as fisherman or sailors left shortly after the industries perished. Today they are most likely retired somewhere in Russia or dead. People do remember the sea, though. You often meet residents who tell you that in the summer of 1980 they used to swim right on the town’s beach (for the last time). And today, the beach is nothing but a stretch of sand on the edge of the dry harbor littered with rusting hulls of ships.

The Morning News: What are your processes when photographing in these locations?

Wyatt Gallery: I usually work alone or travel with another photographer friend, where we would then work separately. I shoot mostly with a 4x5 camera on a tripod and never use and lights. Sometimes I use a 6x7 camera for objects on the ground or portraits. I shoot one sheet of film for every scene I find. Rarely will I shoot more than one. I don’t have many specific locations that are my destinations. I just try to let the photographs find me.

Radek Skrivanek: Many of the places I visited were far from the populated areas, often where the sea once was. Since there are no paved roads, maps, or services of any kind, traveling has its own challenges. I always hire a local driver who knows the area well, and has some ties to the communities I am planning on visiting. We usually travel with a barrel of gasoline on the back seat holding the supply of fuel for the whole trip. For lodging I mostly rely on the hospitality of the local people, which is legendary, and I am always grateful for it. I use a 4x5 view camera. It is large, bulky, and in many ways resembles a 19th-century piece of cabinetry.

The Morning News: The fact that you are being shown together makes it clear we should find a connection, but what similarities do you see between your photographs?

Wyatt Gallery: I was not familiar with [Radek’s work] until the show, but I’m very, very impressed by it. We both photograph the remnants, what is left behind that informs us of the type of society that once flourished there. These artifacts are descriptions of the society and of the people that are no longer there.

Radek Skrivanek: [It was] not until the show at PEER Gallery where I met Wyatt, [that I] first saw his work. I was very impressed by Wyatt’s work and his commitment to photograph the aftermath of hurricane Katrina. Though our projects are from the opposite sides of the planet, and may seem unrelated, there are many similarities. I think we both like to tell these stories, and hope that by sharing them with the public we can make a difference. I fear that our photographs of abandonment, destruction, and hardship are not only documents of what has happened in the past but could very easily be a preview of what future holds for us all.

The Morning News: These disasters and the hardship they’ve cause require so much urgent action and restoration. Are activism and social justice goals of your work?

Wyatt Gallery: Yes, I wish they could be more [of a] part of it, too. I want these photos to affect others. I want them to begin to bridge the gap of understanding how bad this disaster was. I want the photos to force people to slow down and examine this tragedy in an intimate way. These photographs are more intimate than those the general public has seen in the news from Hurricane Katrina.

The Morning News: What is your personal relationship to the location you’ve shot and the events that occurred there?

Radek Skrivanek: I was born and raised in Eastern Europe under the same Communist regime that governed over the then-Soviet Central Asia, where the Aral Sea lies, though the regimes in eastern Europe always had a bit more of a human face than the one in the U.S.S.R. I think I have a unique perspective on the plight of the people in Aral Sea region: I have always known (was taught at school) about the bold and monumental projects that the U.S.SR was undertaking, whether to improve the lives of its citizens or to gain international prestige. These projects, when failed, were equally monumental in their consequences, and the effects of these failures will linger for decades or centuries to come.

The Morning News: Wyatt, are you haunted by images and ideas of the floods and the events in New Orleans, or are you more actively focused on the aftermath?

Wyatt Gallery: I am not interested in documenting the cycle of rebirth of New Orleans. I tried this in Sri Lanka and it didn’t work out. Maybe to shoot the same exact scene in a year would be interesting comparison but mainly it’s the aftermath and the remnants that fascinate and move me emotionally and force me to photograph. I don’t enjoy photographing the aftermath of these disasters, but I do feel very fulfilled by doing it. Everyday that I was in New Orleans I had to force myself out of bed to continue documenting these unbelievable scenes. After about a week and a half I would begin to get nightmares in which I was sleeping in the rubble and debris and mud of people’s homes. I would then leave and go home.

The Morning News: How did you feel about Robert Polidori’s exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art last year?

Wyatt Gallery: I was not impressed. He has been of my favorite photographers but this time around I feel he just recorded different scenes and did not break the surface level the aftermath. I feel the photographs were the scenes that we all saw while we were there. The photographs are made better because his name is on them. My photographs pierce the surface and give an intimate view as well as document it. My photographs should have been in the Met and published in a book.