American Cities

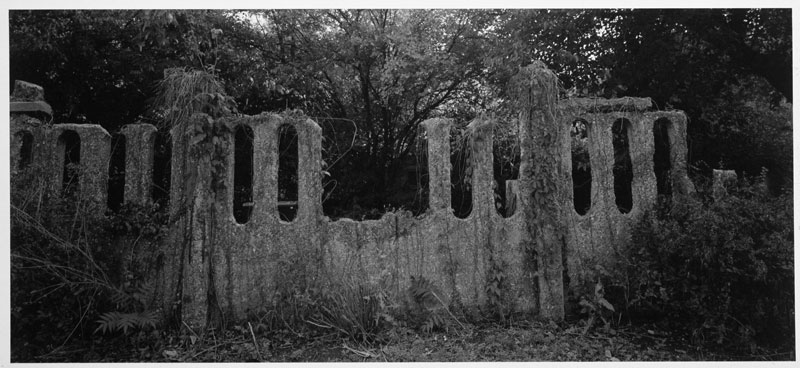

Catherine Opie photographs the backbone and the marrow of American cities. These portraits show not only a city’s architecture, but its character.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

Nicole Pasulka: Why were you initially drawn to photograph cities?

Catherine Opie: I live in L.A. and I’ve always been interested in the formation of communities and in ideas about how architecture affects the formation of communities. I read a lot of urban theory and I wanted to look at the worlds we construct for ourselves. Continue reading ↓

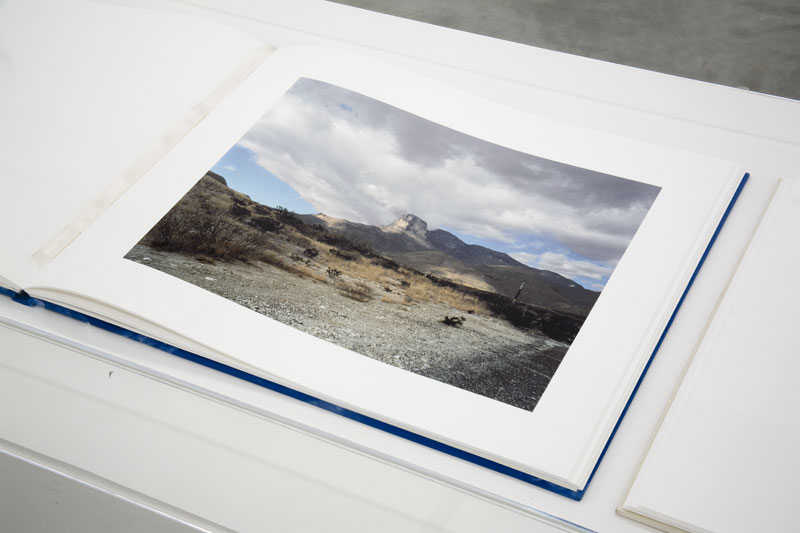

American Cities was recently shown at Gladstone Gallery in New York City; all images are copyright © Catherine Opie and appear courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Interview continued

NP: How do you choose which cities to photograph?

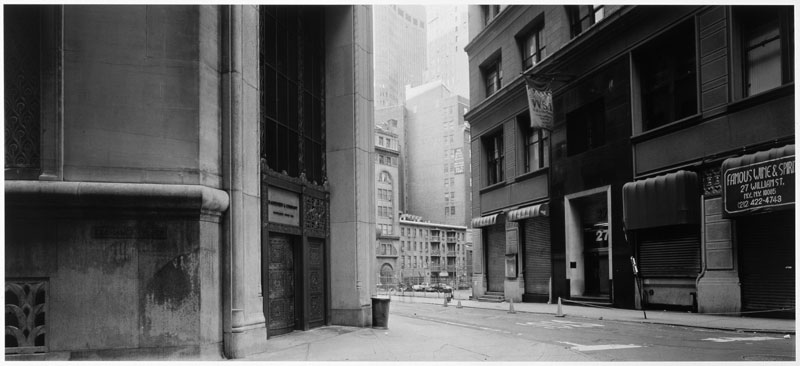

CO: I’m interested in documenting the specificity of urban identities. Not every city has this, but the cities I’ve photographed do. For example, St. Louis was the site of the 1904 World’s Fair. That was the city’s greatest moment. Chicago is the city of architecture. Also, a lot in Chicago is focused around the lake [Lake Michigan]. In New York City, I shot Wall Street, and when I did, I had no way of knowing that one month later the Trade Towers would fall.

NP: Before you begin photographing, do you know what you want to document in a particular city?

CO: Going in, I have things pretty well conceptualized, but I also like to wander around. I explore visually, and that can determine what I photograph. Minneapolis became ice houses and skyways because that’s what I responded to.

NP: But why were you drawn to the Minneapolis skyways?

CO: The skyways form a bizarre connection between buildings. Architecturally, the skyways don’t really match the buildings. It is incredible that you can walk over seven miles through downtown in the skyways. I’d done photographs of freeways in L.A. and I thought of them the same way—as connectors. It was interesting that people had figured out a way to connect downtown businesses in Minneapolis by skyways. How practical! Though freeways in L.A. do the same thing, their construction has also destroyed a lot of communities.

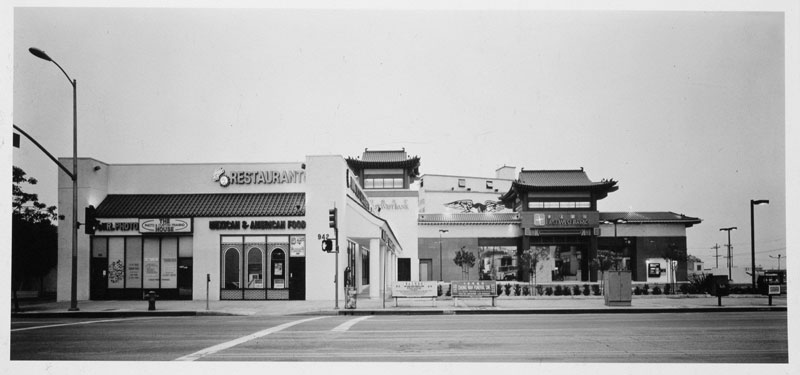

NP: In American Cities, you photograph popular and accessible spaces. However, these spaces are almost always empty—no people, no cars. Why photograph empty metropolitan centers?

CO: I’m interested in photographic history. If I photographed these places with people in them, my work would become street photography. I want my work to be about buildings and places. I don’t use any digital manipulation in my work. I wait for these areas to be empty.

NP: Is there a relationship between an empty strip mall in Los Angeles and Wall Street in New York City?

CO: These places look a very specific way. I’m just exploring that. It is more complicated to do this than it is to talk about it. I’m out there with a seven-by-seven-inch “banquet” camera and [the process] is very physical.

NP: Many of your well-known works are portraits. Do you have a different method or experience when photographing cityscapes rather than people?

CO: I don’t know if there is that much difference. My photographs are portraits of the city in the most simplified form. Even though [the subjects of American Cities] are architectural, each picture is distinct in the same way that portraits are distinct.

When I was taking portraits of queer people in the ‘90s, it was somewhat about documenting the architecture of the queer community. In the queer community, the architecture [appears] on the body. But, that project was also about recording a community that was disappearing because my friends were dying of AIDS.

NP: Your photographs raise questions about the stability and the sterility of man-made structures. Are the buildings and structures you photograph fixed and permanent?

CO: For me, it’s more about memory. I guess that, in some ways, memory could be about permanence. All the American cities are untitled; I don’t want to tell you where I am. And part of that is about recognition. If you’re going to recognize these locations, that’s great. But, I don’t want it to be textbook. I’m more interested in the [audience’s] connection.

NP: Do you see yourself as a documentarian or an artist?

CO: People always come up to me and ask, “Are you an artist or a photographer?” I’m very rooted in the documentary practice. Throughout my life, looking at photographs in history books has informed me. However, people think that if you say you are a documentary photographer, you are a journalist. If you say that you are a fine-art photographer, then people think you are Ansel Adams.

I hope that my work relates on a lot of different levels. That was my goal with the early portraits. I wanted to make them seductive. I think that my work is political and also observational. I hope that, like a good novelist, there are a lot of accumulated stories and that, after a while, the work makes sense.