American Library

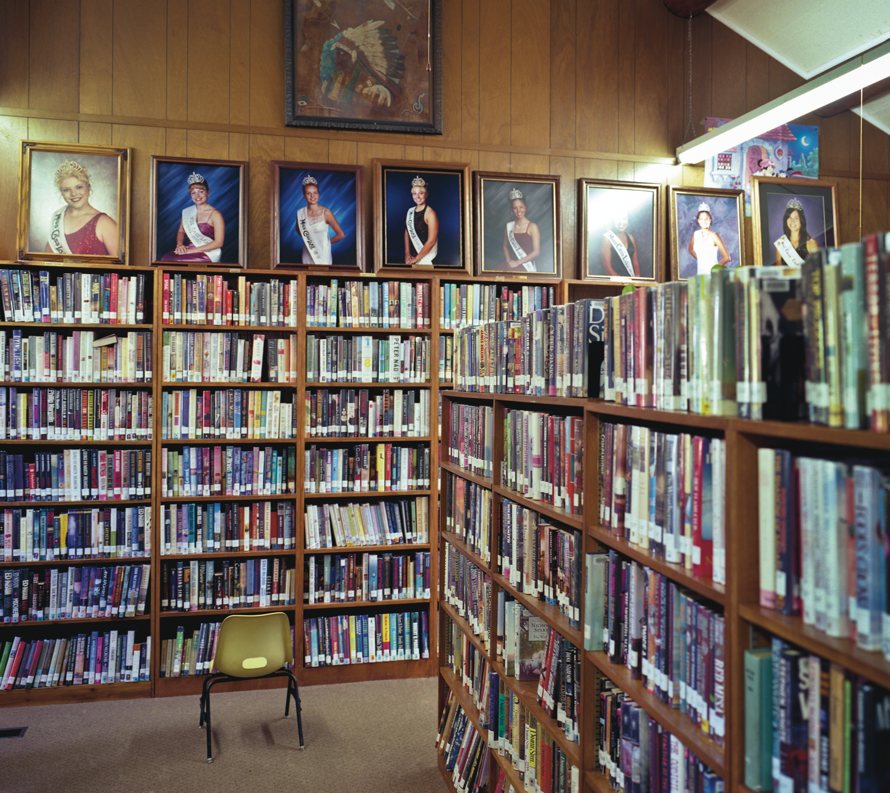

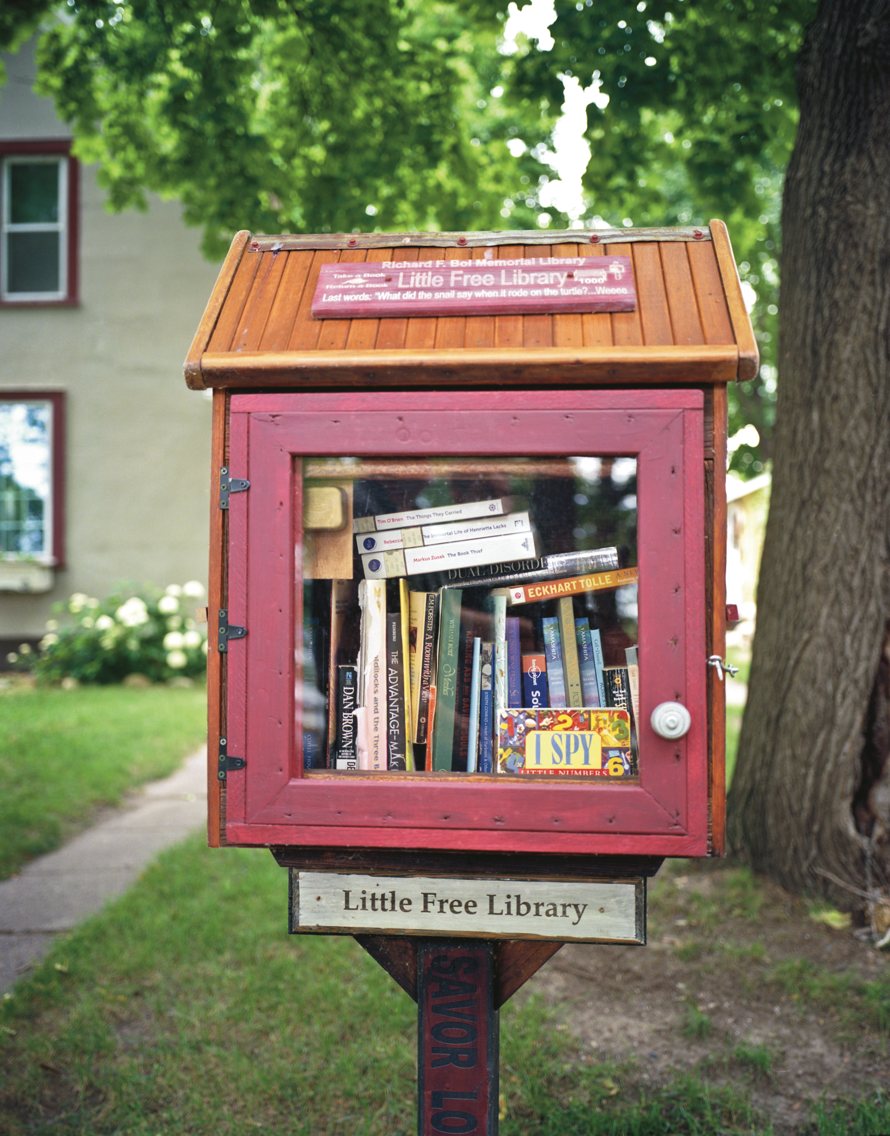

Photographs from a new book of American public libraries—some famous, some neglected, some both—plus an essay by former Poet Laureate Charles Simic.

Photographer Robert Dawson writes:

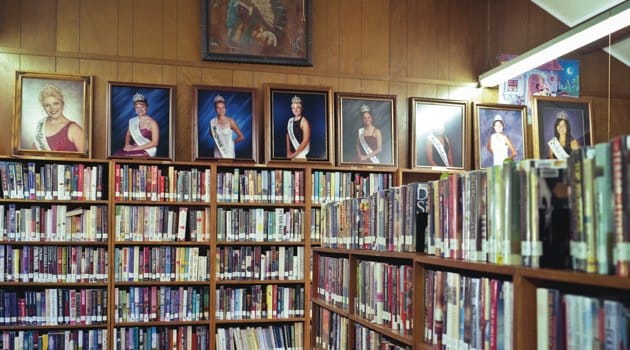

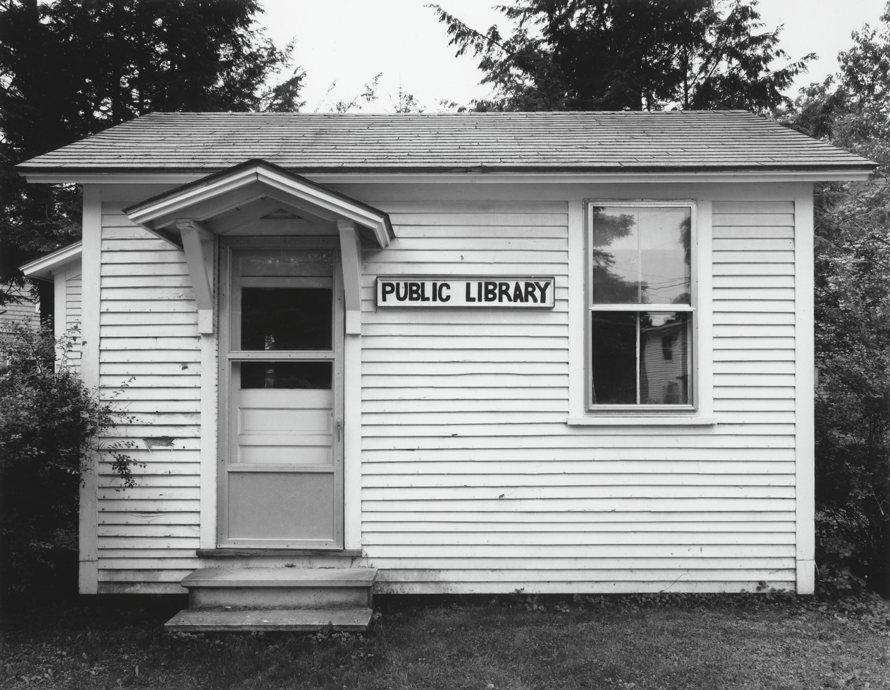

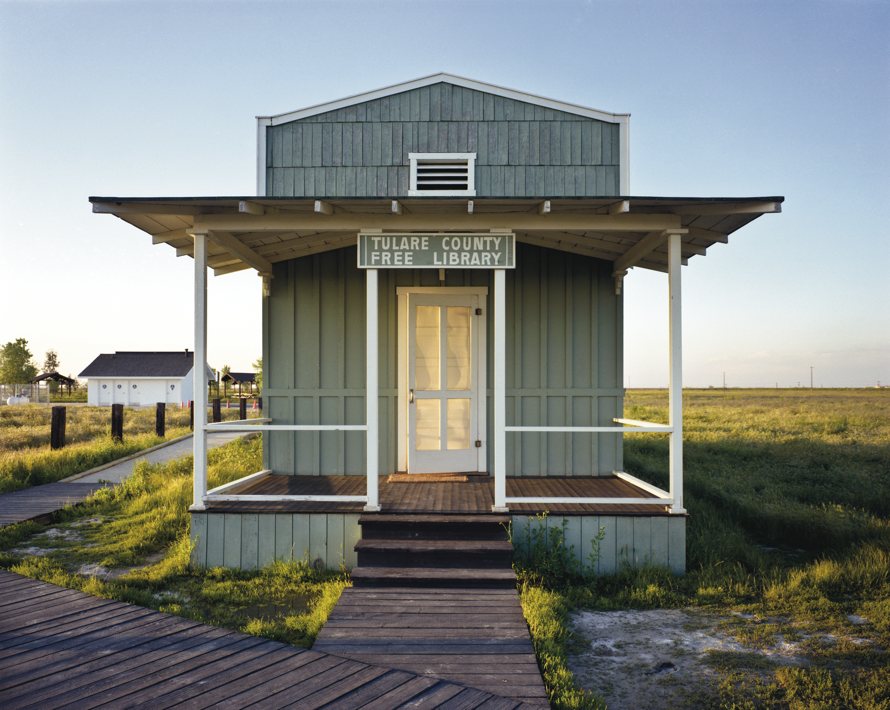

There are over 17,000 public libraries in this country. Since I began the project in 1994, I have photographed hundreds of libraries in 48 states. From Alaska to Florida, New England to the West Coast, the photographs reveal a vibrant, essential, yet threatened system.

...

A public library can mean different things to different people. For me, the library offers our best example of the public commons. For many, the library upholds the 19th-century belief that the future of democracy is contingent upon an educated citizenry. For others, the library simply means free access to the Internet, or a warm place to take shelter, a chance for an education, or the endless possibilities that jump to life in your imagination the moment you open the cover of a book.

Read the essay by Charles Simic ↓

All photographs from The Public Library: A Photographic Essay by Robert Dawson, courtesy Princeton Architectural Press, all rights reserved.

A Country Without Libraries

The following essay by Charles Simic is excerpted from The Public Library: A Photographic Essay by Robert Dawson, published by Princeton Architectural Press, 2014.

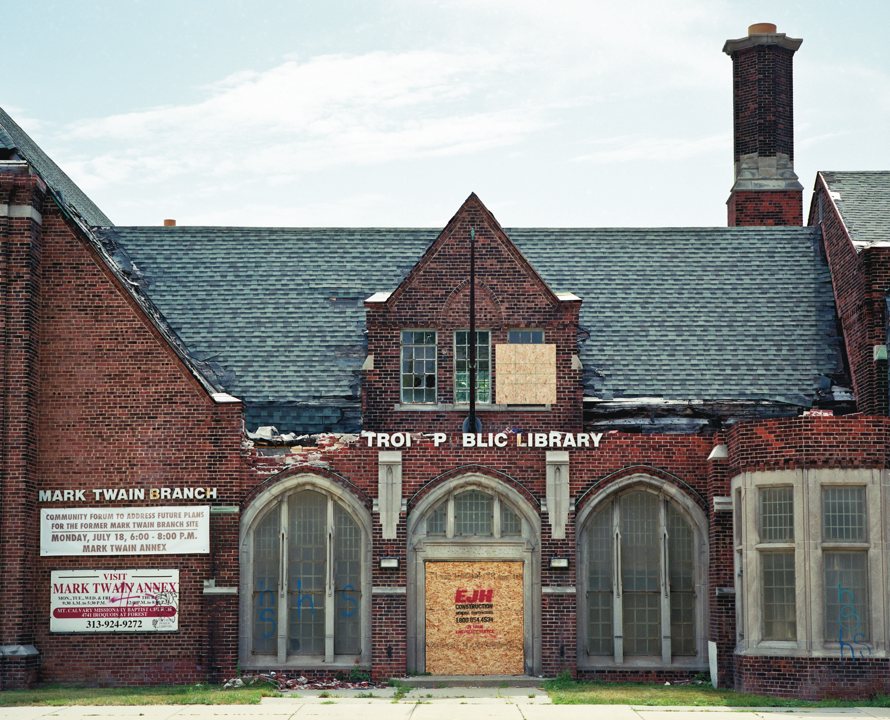

All across the United States, large and small cities are closing public libraries or curtailing their hours of operations. Detroit, I read a few days ago, may close all of its branches and Denver half of its own: decisions that will undoubtedly put hundreds of its employees out of work. When you count the families all over this country who don’t have computers or can’t afford Internet connections and rely on the ones in libraries to look for jobs, the consequences will be even more dire. People everywhere are unhappy about these closings, and so are mayors making the hard decisions. But with roads and streets left in disrepair; teachers, policemen, and firemen being laid off; and politicians in both parties pledging never to raise taxes, no matter what happens to our quality of life, the outlook is bleak. “The greatest nation on earth,” as we still call ourselves, no longer has the political will to arrest its visible and precipitous decline and save the institutions on which the workings of our democracy depend.

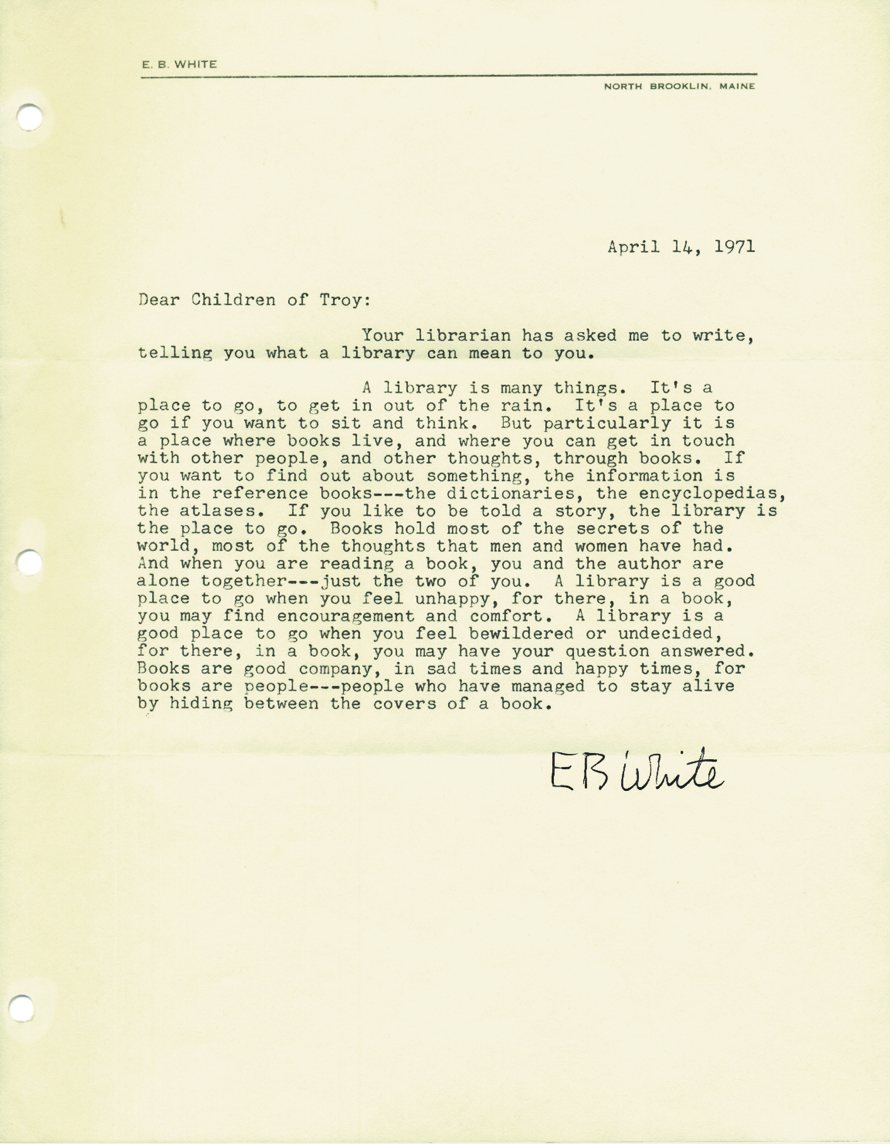

I don’t know of anything more disheartening than the sight of a shut-down library. No matter how modest its building or its holdings, in many parts of this country a municipal library is often the only place where books in large number on every imaginable subject can be found, where both grownups and children are welcome to sit and read in peace, free of whatever distractions and aggravations await them outside. Like many other Americans of my generation, I owe much of my knowledge to thousands of books I withdrew from public libraries over a lifetime. I remember the sense of awe I felt as a teenager when I realized I could roam among the shelves, take down any book I wanted, examine it at my leisure at one of the library tables, and if it struck my fancy, bring it home. Not just some thriller or serious novel, but also big art books and recordings of everything from jazz to operas and symphonies.

In Oak Park, Illinois, when I was in high school, I went to the library two or three times a week, though in my classes I was a middling student. Even in wintertime, I’d walk the dozen blocks to the library, often in rain or snow, carrying a load of books and records to return, trembling with excitement and anticipation at all the tantalizing books that awaited me there. The kindness of the librarians, who, of course, all knew me well, was also an inducement. They were happy to see me read so many books, though I’m sure they must have wondered in private about my vast and mystifying range of interests.

I’d check out at the same time, for instance, a learned book about North American insects and bugs, a Louis-Ferdinand Céline novel, the poems of Hart Crane, an anthology of American short stories, a book about astronomy, and recordings by Bix Beiderbecke and Sidney Bechet. I still can’t get over the generosity of the taxpayers of Oak Park. It’s not that I started out life being interested in everything; it was spending time in my local, extraordinarily well-stacked public library that made me so.

This was just the start. Over the years I thoroughly explored many libraries, big and small, discovering numerous writers and individual books I never knew existed, a number of them completely unknown, forgotten, and still very much worth reading. No class I attended at the university could ever match that. Even libraries in overseas army bases and in small, impoverished factory towns in New England had their treasures, like long-out-of-print works of avant-garde literature and hard-boiled detective stories of near-genius.

Wherever I found a library, I immediately felt at home. Empty or full, it pleased me just as much. A boy and a girl doing their homework and flirting; an old woman in obvious need of a pair of glasses squinting at a dog-eared issue of the New Yorker; a prematurely gray-haired man writing furiously on a yellow pad surrounded by pages of notes and several open books with some kind of graphs in them; and, the oddest among the lot, a balding elderly man in an elegant blue pinstripe suit with a carefully tied red bow tie, holding up and perusing a slim, antique-looking volume with black covers that could have been poetry, a religious tract, or something having to do with the occult. It’s the certainty that such mysteries lie in wait beyond its doors that still draws me to every library I come across.

I heard some politician say recently that closing libraries is no big deal, since the kids now have the Internet to do their reading and schoolwork. It’s not the same thing. As any teacher who recalls the time when students still went to libraries and read books could tell him, study and reflection come more naturally to someone bent over a book. Seeing others, too, absorbed in their reading, holding up or pressing down on different-looking books, some intimidating in their appearance, others inviting, makes one a participant in one of the oldest and most noble human activities. Yes, reading books is a slow, time-consuming, and often tedious process. In comparison, surfing the Internet is a quick, distracting activity in which one searches for a specific subject, finds it, and then reads about it—often by skipping a great deal of material and absorbing only pertinent fragments. Books require patience, sustained attention to what is on the page, and frequent rest periods for reverie, so that the meaning of what we are reading settles in and makes its full impact.

How many book lovers among the young has the Internet produced? Far fewer, I suspect, than the millions libraries have turned out over the last hundred years. Their slow disappearance is a tragedy, not just for those impoverished towns and cities, but for everyone everywhere terrified at the thought of a country without libraries.