America’s Other Audubon

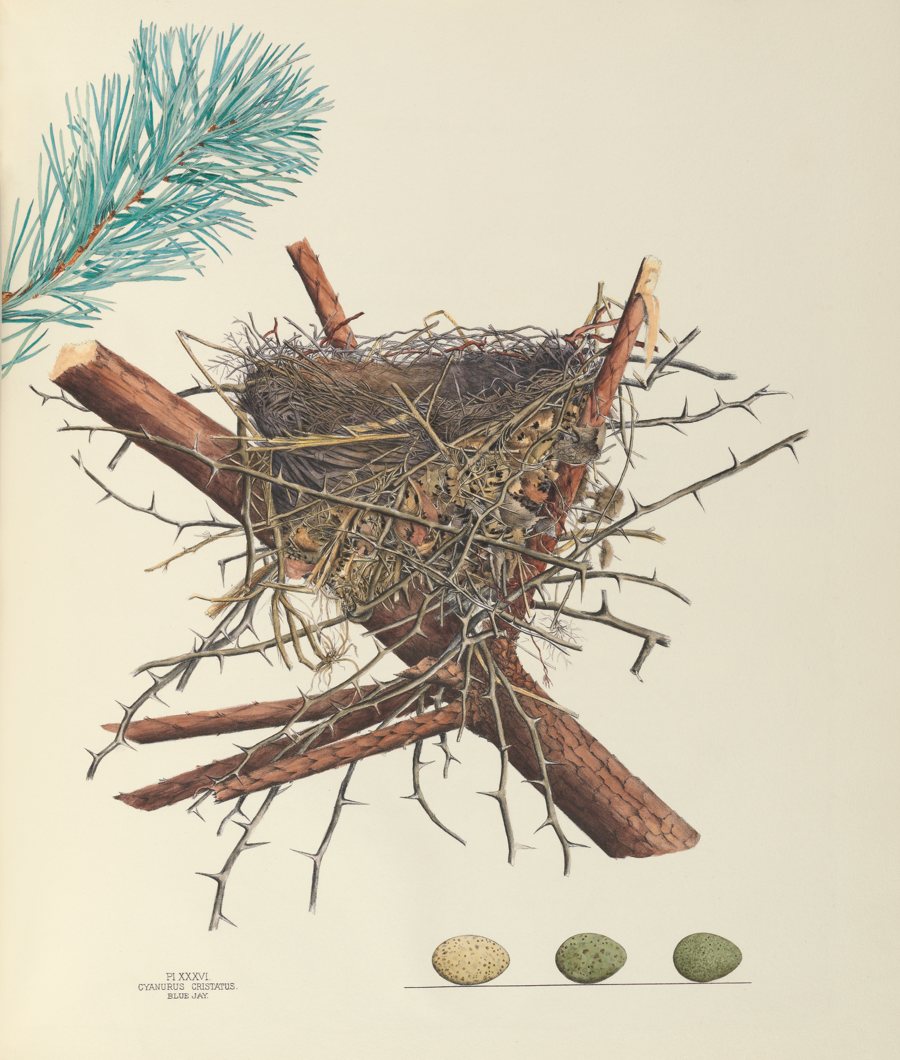

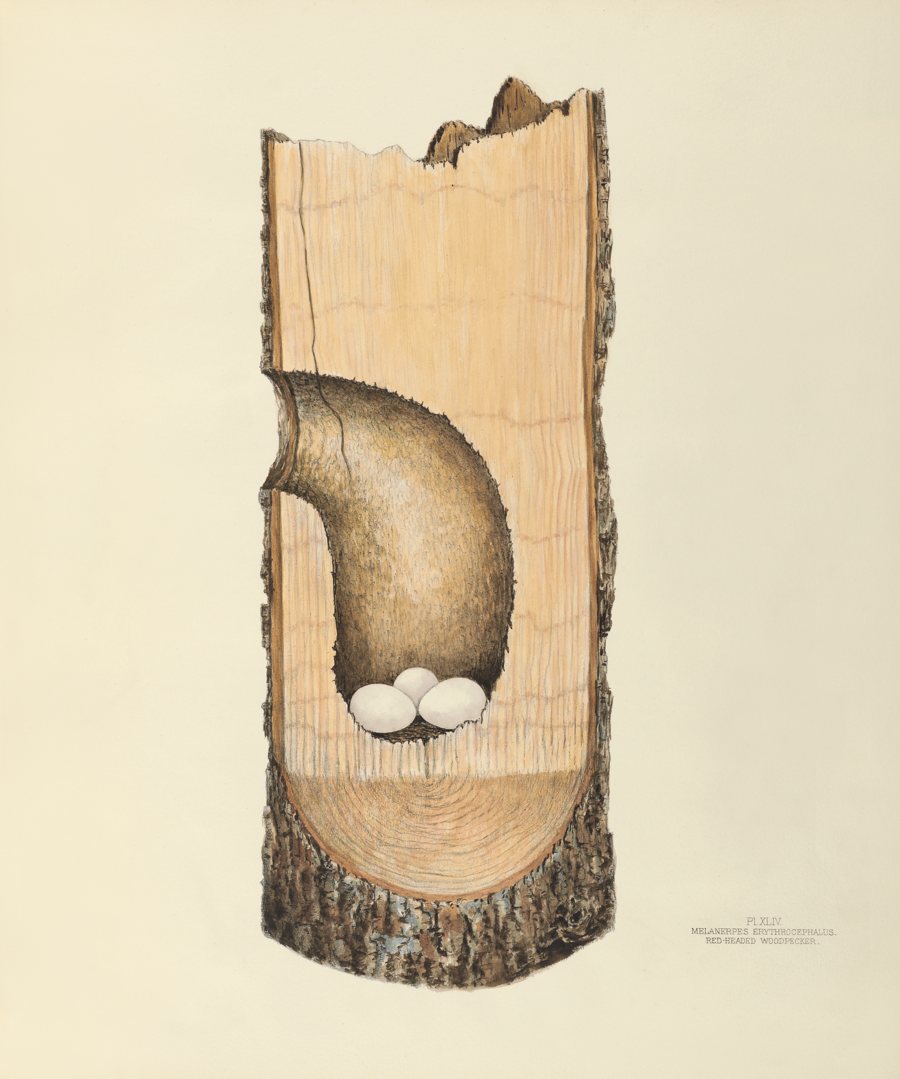

Selections from the monumental but unknown “Illustrations of the Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio,” an amateur’s attempt to illustrate the nests and eggs omitted from John James Audubon’s “Birds of America.”

As the publisher of America’s Other Audubon notes:

Inspired by viewing Audubon’s lithographs at the 1876 World’s Fair in Philadelphia, 29-year-old amateur naturalist and artist Genevieve Jones began working on a companion volume to The Birds of America, illustrating the nests and eggs that Audubon omitted. Her brother collected the nests and eggs, her father paid for the publishing, and Genevieve learned lithography and began illustrating the specimens. When Genevieve died suddenly of typhoid fever, her family labored for seven years to finish the project in her memory.

The original book was sold by subscription in 23 parts. Subscribers at the time included included Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and Theodore Roosevelt. But fewer than 25 copies of the volume now remain.

Joy Kiser’s America’s Other Audubon reproduces all 68 original color lithographs (they also make for nice notecards), and also includes archival photographs, field notes, and a key to the eggs and birds.

What can we say—we didn’t know we’d find nests so intriguing.

In the excerpt below, Kiser recounts of the joy of discovery from when she first encountered volume one of Illustrations of the Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio. Continue reading ↓

Excerpted with permission from America’s Other Audubon by Joy M. Kiser, published by Princeton Architectural Press, 2012. All images used with permission, all rights reserved.

From the Preface

On May 22, 1995—an idyllic spring morning—I walked into the Cleveland Museum of Natural History in Ohio, full of anticipation and eager to begin my new position as assistant librarian. Volume one of Illustrations of the Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio was exhibited in a Plexiglas display case at the foot of the stairway that led to the library on the second floor. A label, about three inches high by five inches wide, succinctly explained that the book was the accomplishment of the Jones family of Ohio: the daughter, Genevieve, had conceived of the idea and had begun drawing and painting the illustrations with the assistance of a childhood friend; the son, Howard, had collected the nests and eggs; the father, Nelson, had paid the publishing costs; and after Genevieve died, the mother, Virginia, and the rest of the family spent eight years completing the work as a memorial to Genevieve.

The book was on exhibit for several weeks. Each morning as I climbed the stairs, I would gaze at the label in the case and then into the faces of the members of the Jones family, whose photographs had been tipped onto the page adjacent to the illustration being displayed in the exhibit case. I became increasingly bewildered that eight years of work could be summed up on such a tiny label in so few words, and with such a lack of emotion. I found Genevieve ‘s face almost haunting—her large, expressive eyes full of expectancy and hope. Was this book the only thing that was left to represent her life? What kind of person was she that she would inspire her entire family to devote so much of their own lives to completing her undertaking? Surely, her story must be one filled with passion. But the exhibit came to an end, the book was returned to a climate-controlled vault far from the main library, and my thoughts about Genevieve and her family were left to simmer on the back burner in my mind.

Then in March of 1997, a dear friend passed away unexpectedly. After his funeral, I returned to work, where I encountered a notice for a conference of the international Society for the History of Natural History that had been posted on the rare book listserv Exlibris by Leslie K. Overstreet, the curator of Natural-History Rare Books at the Smithsonian Institution Libraries. The conference would take place at the University of Virginia (UVA). I discussed the event with the head librarian, David Condon, and he encouraged me to apply to the Smead Staff Enrichment Fund for financial support to attend.

A few weeks later, I was on a plane flying out of a snow-covered Cleveland, and within hours I was descending into a blossom-filled spring day in Charlottesville, Virginia. The conference was fascinating. Scholars from world-renowned libraries presented papers on natural history. The attendees toured the grounds of the university, visited Monticello, and viewed Rachel Lambert Mellon’s Oak Spring Garden Library, a private collection of rare books, manuscripts, works of art relating to botany, horticulture, gardening, landscape design, natural history, and travel. The sunshine, visual and intellectual stimulation, and pleasant interaction with people who shared similar interests were uplifting. The theme of the society’s next conference, to be held in 1999 at the Natural History Museum in London, was natural history illustration. I remembered Genevieve ‘s book. A search of the UVA’s library catalog revealed that they owned a copy. I wondered how many other libraries had the volume in their collections.

When I returned to work, I searched the Online Computer Library Center catalog but could only locate a few libraries that owned the book. Not surprisingly, most copies of the book were held at libraries and historical societies in Ohio. The catalog description indicated that only one hundred copies had been made. The rarity of the book piqued my interest—would a research paper chronicling the creation of the illustrations for this book be unique enough to be accepted for inclusion in the London conference? It seemed likely that any primary sources that existed would be within driving distance, so the cost of doing the research would be reasonable, and I felt sure that if my paper was accepted it would bring positive attention to the library’s rare-book collection.

On April 14, 1999, I gave my first professional presentation at the conference on natural history illustration in the Natural History Museum in London. It was not immediately apparent how the topic had been received. Only two women from the audience came up to say how much they had enjoyed the Jones’s story. For the rest of the evening and the following morning, I wondered whether a book created by a family from a small town in Ohio was equal to the works of Alexander Wilson, Mark Catesby, or John James Audubon.

When the meeting reconvened, the conference leader opened by referring to my presentation and, to my delight, informed the audience that the museum owned a copy of the Illustrations of the Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio. The book would be on display in the archives during the first break so that those interested could take a look at it.

Later, when the archives library was filled with admiring conference attendees carefully turning pages and examining details of the lithographs, the archivist confided that he was planning to include Illustrations of the Nests and Eggs of Birds of Ohio among the special volumes he pulled to show visiting royalty or heads of state, because of the beauty of its illustrations and the heartfelt story of the family behind its creation. I felt relieved and proud that Gennie’s book was destined to be recognized by such a prestigious institution.