What brought you to Mumbai in the first place?

Alicja Dobrucka:I first came to Mumbai at the end of 2011 for a residency and an exhibition, and honestly I didn’t dare pull out my camera. I find India is rather difficult to photograph, as it’s just too photogenic. I kept coming back to the city, and it wasn’t until two years later, in 2013, that this series actually came about.

TMN:Tell us about the trickiest part of making these images.

AD:Shooting the series was not an easy task, considering that I chose to execute it with a large format camera, so the process became much slower. The most demanding, trickiest, and time-consuming part was actually receiving permission as each building has a guard downstairs. It is not a problem to walk around with any digital equipment, but as soon as you pull out a tripod the problem starts.

There are some areas, like Worli Naka, where people are very aware of photographers and are requested to report anyone taking pictures to the police. It’s an aftermath of the 2008 attacks as there were white photographers doing mapping for Pakistani bombers.

What surprised you during the process?

AD:My assistant Omrita Nandi and I had many adventures while shooting. Mumbai is a place where as a woman you cannot go many places alone. Once when we visited an inhabited building and while asking for permission to photograph, the man we were speaking to—the head of security of that building—unzipped his fly. I wasn’t quite sure whether that really was happening as we did feel we weren’t alone there. We ran a floor down and, in panic, tried to ask the family who were living there who was the secretary. Each building in Mumbai has someone like a director of the decision-making panel, called the secretary. The people refused to speak to us.

This was not the only case of such behavior, which is actually more shocking rather than surprising.

TMN:Could you replicate this series in another city? Let’s say, in London where you live?

AD:Yes, that would definitely be possible in many developing Asian cities. I have recently visited Hong Kong and Istanbul, where I saw some amazingly horrendous construction, and I’m sure I would have a lot of joy capturing them. I’m not sure about London, as the system of centralized urban planning is highly organized there.

TMN:The writer George Saunders, discussing the art of fiction, said art starts with intention and “our intention is to crack life open for just a second.” In what ways have you experienced this through photography?

AD:Ha! I think for me this happens in the process: research, experimenting, and when it all starts coming together. It has to do with the vulnerability caused by the uncertainly of whether it’s going to work out.

TMN:What will this city look like in 10 years?

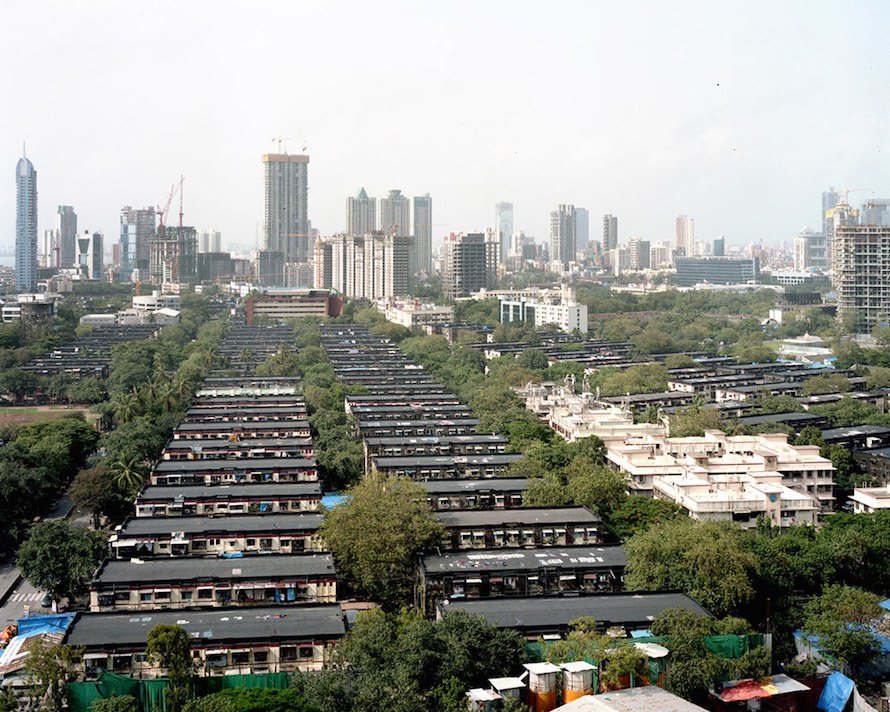

AD:I’m very interested to know that. I presume that the photographed buildings will look much worse once they have lived a little in the moist Mumbai climate.

Mumbai is definitely becoming a vertical city slaved to the car and in which the pavements are bound to disappear. The island city is rapidly expanding onto the mainland.

The way things look like at the moment is that if the small number of people who are aware of the world heritage of the city fail to protect it, all the charming post-colonial architectural leftovers will have disappeared and be replaced by the modern structures with more chain restaurants and coffee shops.

TMN:Where are you taking your camera next?

AD:Just got back from a residency in Sivas, Turkey, organized by the Tandem program participants: Kasia Sobucka, Merja Briñón, Talat Alkan, and Serra Özhan Yüksel. I was working with the local crafts people, as well as on sculptures and paintings and with a local musician on a video piece.

When it comes to photography, the next destinations are Turkey and India. But who knows, things may change. I like to keep an element of spontaneity.