Another Space and Time

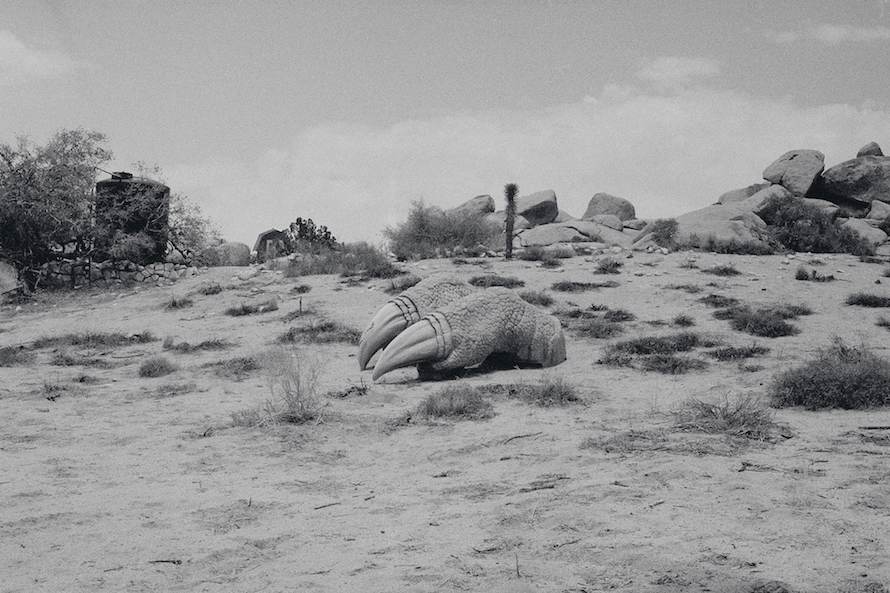

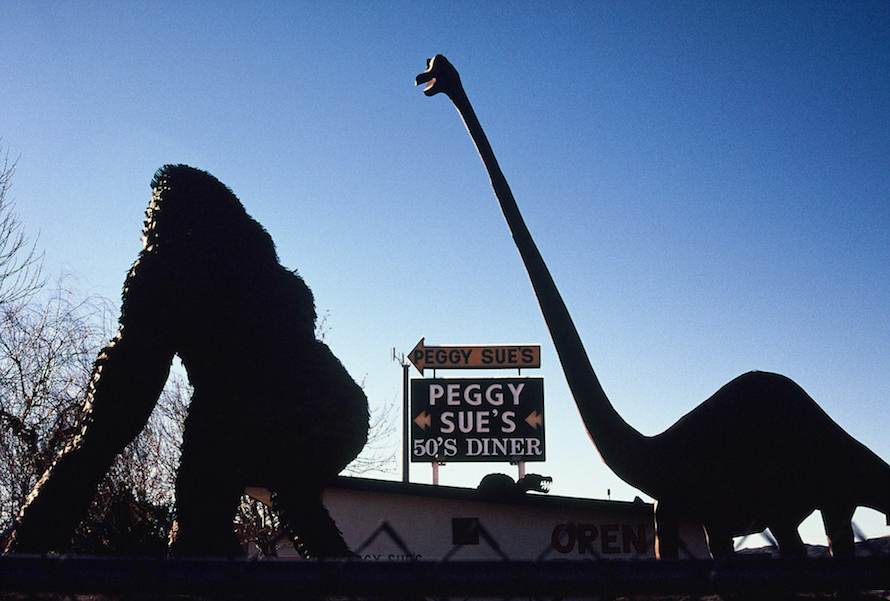

Popular notions of the Great American Desert were of a land barren and uninhabitable. But away from the frills of modern life, photographer Robin Mellor finds answers when he asks his subjects, “What’s the meaning of life?”

Interview by Karolle Rabarison

The Morning News: You asked your subjects to tell you the meaning of life, which is a pretty age-old tradition. Why is this question—and this project—still interesting and important?

Robin Mellor: The meaning of life is definitely not an original question to ask, but it’s not one that is asked very often. I think it’s just too big a question to walk around with day to day. When I was asking this question, however, I tried to lead up to it. It would always be met with a slight sense of shock. Either people just don’t see it coming or are like rabbits in the headlights of the enormity of the question. It’s such a great disarming one to ask someone. There’s no quick response or easy answer. It really slows people down. They need time to ponder their response. Continue reading ↓

Robin Mellor’s latest personal project, ”Another Space and Time,” will be featured throughout Hackney, London, in May 2015 during his first exhibition. All images used with permission, all rights reserved, copyright © the artist.

Interview continued

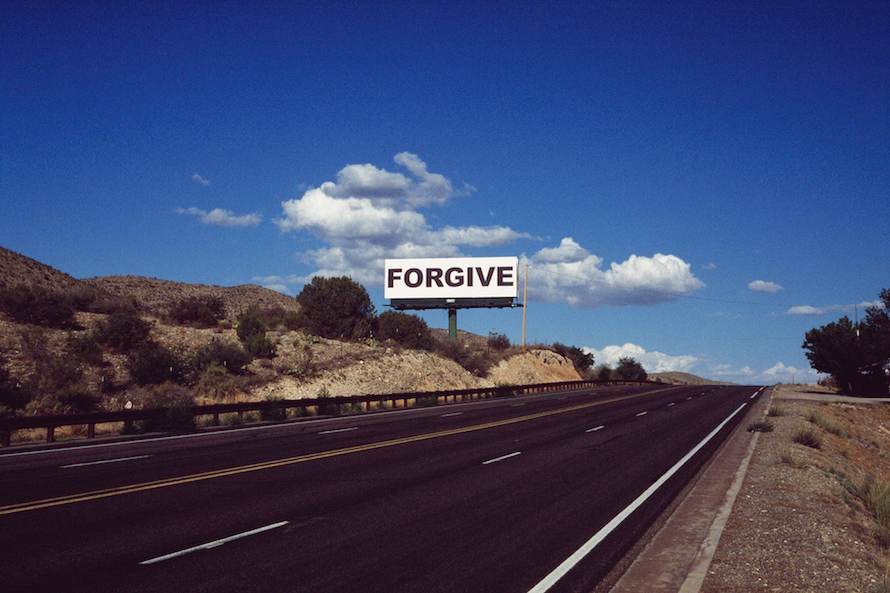

Right now the world is going through huge changes: climatically, socially, financially, and spiritually. I think it would benefit us all to consider this question more regularly. We’re bombarded with all sorts of modern superficial distractions and pressures that make us lose sight of what might be important to us.

By asking this question in the desert, you take away these modern distractions. I found people there to be much clearer in their views of the world—unaffected by our modern societal white noise, having had the mental space and time to fully form their views.

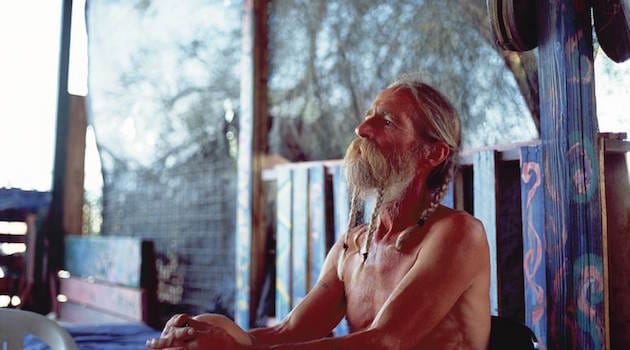

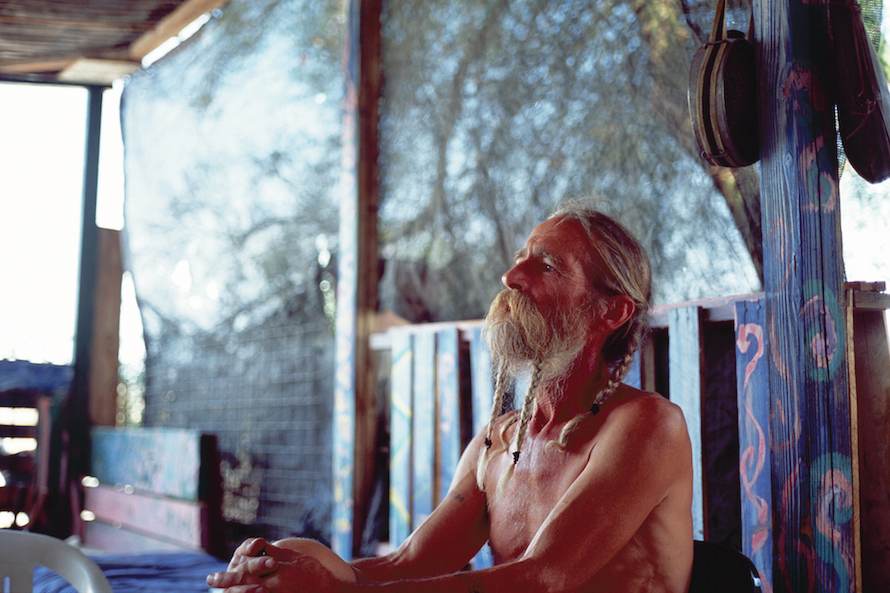

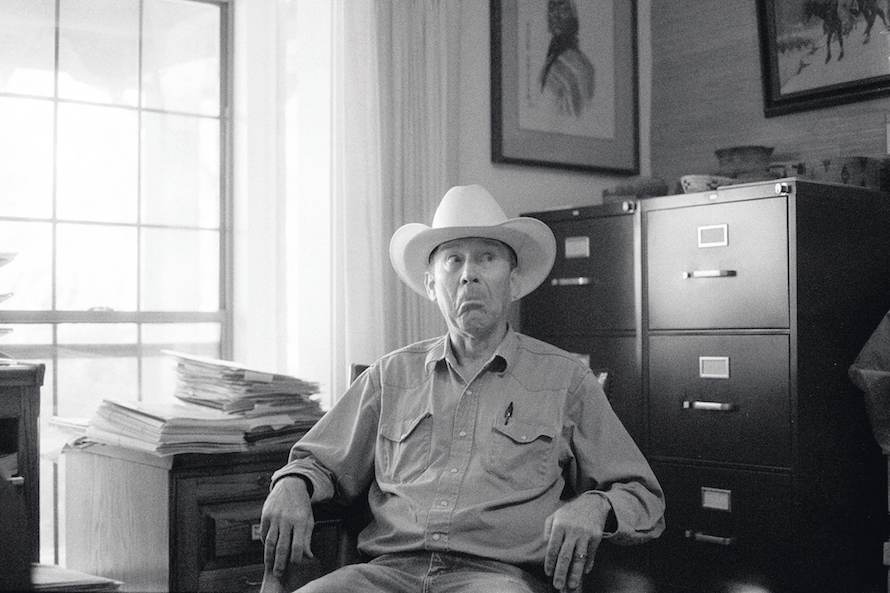

TMN: You’ve mentioned the portrait of Frank is one of your favorite images. What is Frank’s story?

RM: Frank currently lives in Slab City and runs the internet café there. He’s a real free spirit and has lived in one desert town or another for more than 20 years. I love the picture of him. He looks so bold and proud, he reminds me of an American eagle. For me he encapsulates the true freedom of the American spirit.

TMN: The series as a whole gives off a sense of quiet and oneness with the environment. What are some of the more stormy aspects of life in the desert?

RM: The desert is not an easy place to live. It’s a harsh environment, both mentally and physically. And those not willing to work hard, sacrifice, or just are not emotionally ready to live there will not make it. The thing I found, however, is that most people who live there enjoy the hardships. Normal society has become obsessed with comfort and convenience to a degree that is completely unnecessary. We need hardship and challenges in our lives. Without these hardships I think we just create other problems to obsess over.

TMN: Do you see yourself as the kind of person who might embrace such hardships and stay in the desert long-term?

RM: I do think it’s a place I could live in one day. It certainly draws me in. Cathy, one of the ladies I shot for the project, said a great thing to me, “I should warn you. Don’t stay here very long, because if you do, you think you can just leave, but this is actually some kind of a vortex. If you stay here too long, it will suck you back. It’s like a seduction.”

The fact that I’d been to the same place for the first time about three months before, and somehow found my way back so soon, meant I couldn’t really argue with her.

TMN: Many would say that photography is about discovery, poking into new spaces to uncover something unexpected about the world and ourselves. How have you been surprised by this project?

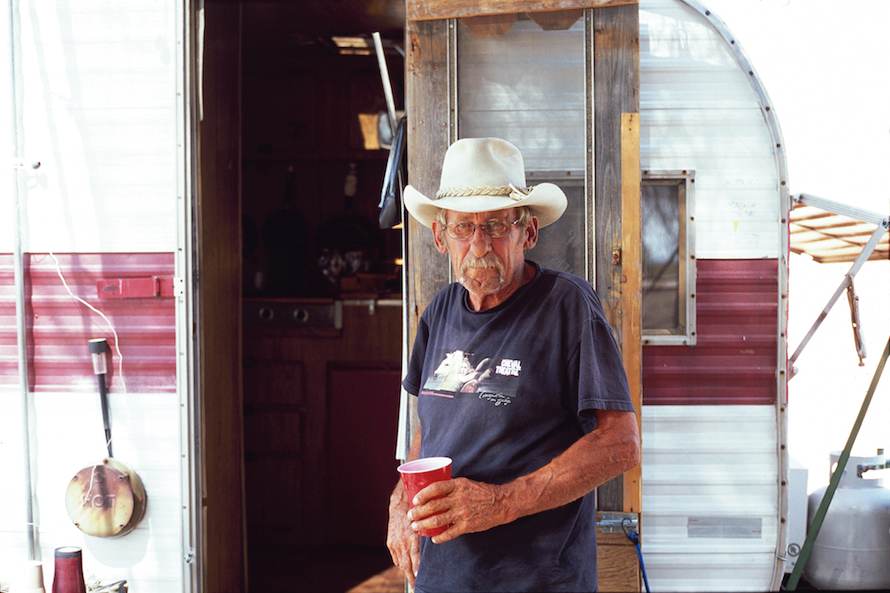

RM: Surprise was pretty much my general state while I was in the desert. The project has taught me so much. I went into it without any agenda or preconceived ideas of what the overall message would be. The people I met shaped the story.

You may think people living in the middle of nowhere—with no running water and having to rely on the sun for power—may be a little backward or primitive. But what I found were communities that were incredibly progressive. We live in a time where the problems of sustainability are at the forefront. And here we have communities that had broken away from the unsustainable system and set up their own societies in the harshest place in the country, yet are still able to live independently and sustainably.

These societies are also incredibly positive and creative places in general. The people there work in communities. When money is not the primary focus of your energy it allows you to operate in a much more collective and less selfish way. As a child of the 1980s, the obsession with wealth and materialism has always been at the forefront of my culture. Meeting people who positively shunned this notion was strange but intriguing. It only took a couple of weeks to adjust, and once I did, it made no sense to live any other way.

TMN: Tell us a bit about the exhibition you’re putting together in Hackney.

RM: The Hackney exhibition is happening throughout May 2015 and is an exhibition of exploration through expedition—bit of a mouthful, I know! It is a walking tour around the streets of Hackney, with the images displayed as huge prints attached to the sides of various buildings along the route. You’ll be guided through the tour via the project app on your smartphone, which will have maps and an audio soundscape made up of interviews, music, and other sounds I collected along the way. I’m working with loads of great people on it and can’t wait see it all in action.