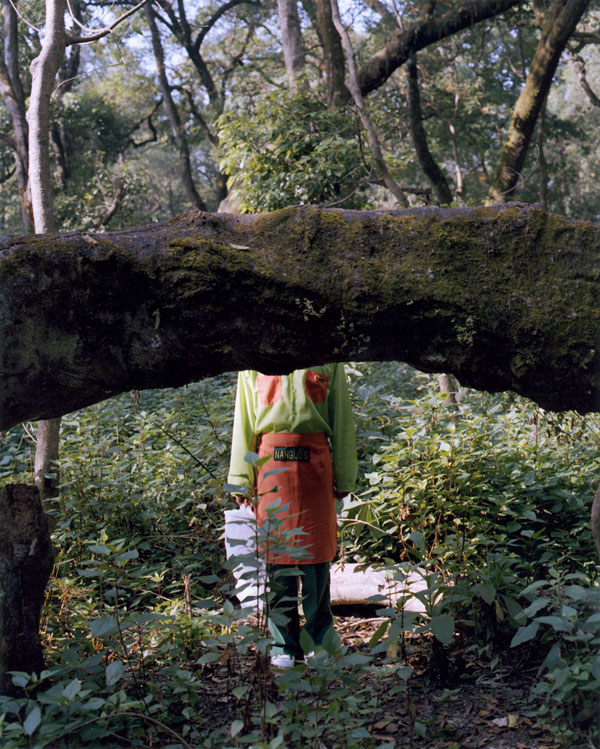

Appearing In

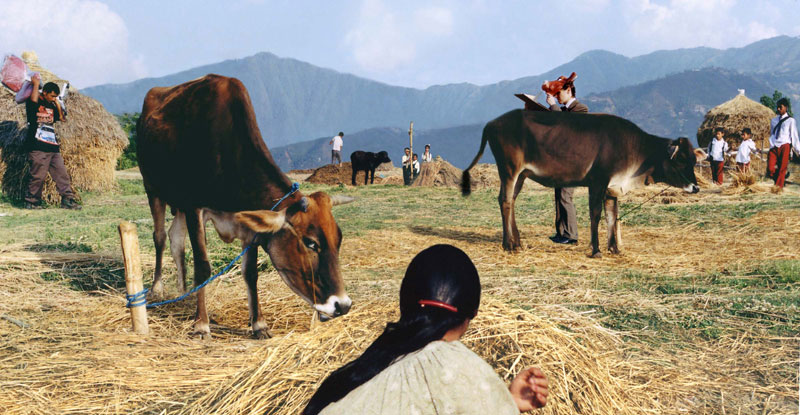

Stuart Hawkins’s humorous photographs self-consciously imagine moments of cultural intersection, challenging the audience to imagine what happens before and after a picture is taken. Her work, charming and somewhat confusing, seems to articulate her own experience as an American living in Nepal.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

Who are the subjects in your photographs?

Some are friends, some are people I meet and photograph on the spot, and some just wander into the frame. As for subject matter, they are supposed to portray not just people from Nepal, but a broader population from places that somehow experience international marginalization economically, racially, or politically. I am also working a lot in Kolkata, India now and have done work in Peru and Mexico. Continue reading ↓

All images courtesy Zach Feuer Gallery. All images copyright © Stuart Hawkins, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

What do the subjects in your photographs represent?

I understand only bits and pieces of ideas and exchanges that I experience in the process of photographing a person or a scene. The most profound moments of understanding usually happen when the camera is absent, but of course this keeps me interested in the process of doing what I do—which is more valuable than the actual picture, perhaps. This innate limitation makes me want to know more and not just rest with the images.

Are tourists insensitive and callous?

No, I don’t think tourists are insensitive or callous necessarily. I do think that they frequently come armed with their own sets of preconceptions. And that can be dangerously limiting. But, learning is about making mistakes and that’s OK, too. There are many different types of tourists, some more culturally sensitive than others, but the meeting place between the tourist and the host culture is the overlap that motivates my art.

Does your work challenge cultural stereotypes, or parody the idea of a cultural truth?

I like to play with templates of cultural stereotypes in my art to raise questions that might address broader socio-political issues. I like to mix things up and see what evolves.

How do you decide what scenes to depict?

Apart from my videos, I have done three major bodies of photographic work. Each body of work developed differently. In Appearing In, for example, it was left up to the subject primarily to create whatever image they desired. However, in the most recent body of work I combined staged elements with un-staged elements.

The scenes I set out to depict are frequently stories I have heard from Nepali friends or situations I have experienced firsthand. I take this idea and create a type of performance that interacts with the public, and then I photograph it. It is not a static depiction of a thing I envisioned in my head. I like inviting chance, especially [since it] by and large seems to underscore the original scene. It becomes a bit of life imitating art and art imitating life.

How did you end up in Nepal?

I came to Nepal in 1991 on a study-abroad program. My main objective was to immerse myself in a country that was totally foreign to me. Nothing in particular about Nepal attracted me. I only [wanted] to live in a place that was outside the very homogeneous environment I grew up in. In that regard, I could have just as easily spent all this time in many other countries; it just happened to be Nepal.

Why have you stayed so long?

I was very confused my first few months in Nepal. I was studying with students who were specifically focused on [things] that pertained to Nepali or Tibetan culture. I was less curious about the specifics and spent a lot of time removed from the group watching from afar. Although I wanted to learn as much as possible about the country I was living in, I was particularly drawn to the subject of “us” studying “them,” and this just didn’t seem pertinent or maybe even acceptable to pursue. However, this intrigue evolved from something abstract and at times subconscious, to a more realized subject that I wanted to make art about. There was a lot of trial and error in finding a comfortable place to visually express my ideas and observations. But staying in one country simplified this process (though I should add I don’t consider my work to be about Nepal, rather the issues that Nepal and many other countries confront). Also, my friends here have kept me coming back.

How would you describe your relationship to the country now?

That is a hard question to answer. At times I feel very close to Nepal as my life here is so intimately ordinary. But, perhaps this is a false perception. I will never be Nepali. I will always be a foreigner. This [presents] many insurmountable differences that automatically set me apart. So, I guess my relationship is more like sitting under your favorite tree and watching it grow over many years. I am with it but we are separate.

Can you identify some differences you see between Nepalese culture and American culture?

Again, tough question. There are superficial differences and deeply rooted differences. This is an immense topic that would be better suited for a dissertation, and my artwork does not aim to compare the two. But, the one thing that always strikes me the most in going back and forth between the two countries is the idea of the individual. Americans are very ‘me’-centric and career-driven and Nepal is more family- and community-centered. I miss this a lot in New York, especially when people ask you at a party what you do as opposed to how you are.

Are there American influences present in Nepalese culture?

I am not sure I know at this point. Everything is so immediate and available today. For example, it used to be more apparent what came from India and what came from America. Now it is all so intertwined, [because] there is equal access to information and entertainment. This greatly interests me: thinking about and understanding culture in a different light, abandoning some of the older and more obvious cues.

Your work is bright and beautiful, and it also seems to be full of social commentary. Do you feel your work is at all subversive?

I don’t think there is anything negative about my work. Though it addresses issues that are quite serious and not intended to be funny, the work has to have a sense of humor for me to feel moved by it. If we don’t have the simple ability to laugh at ourselves, then I am not sure how we are ever going to get this world out of the mess that it is in. People have called my work “dark” before, but I am only poking fun lovingly at humanity.