Between Floating and Falling

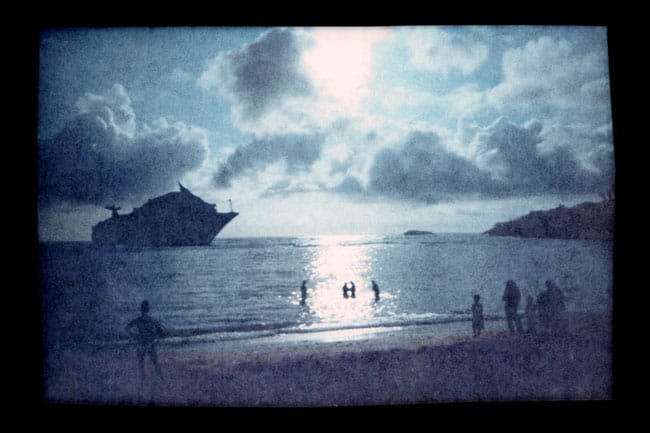

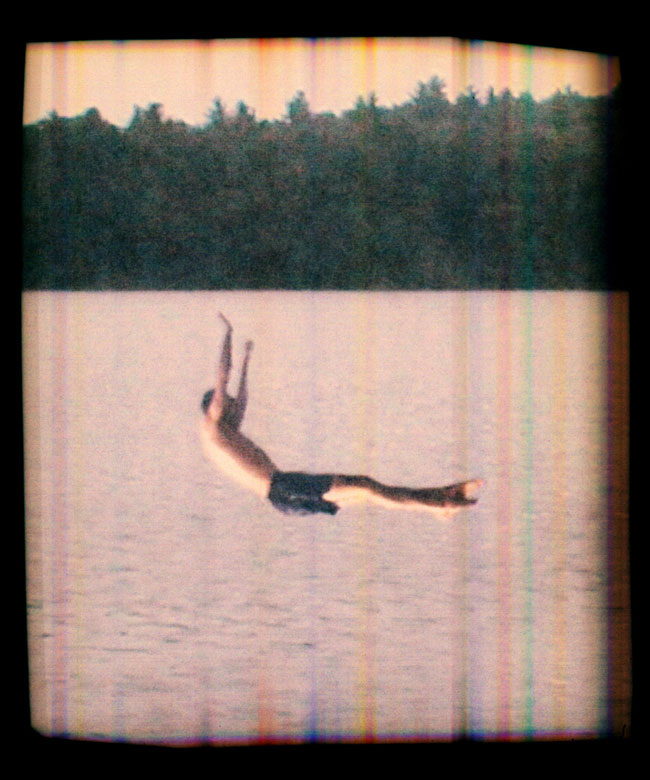

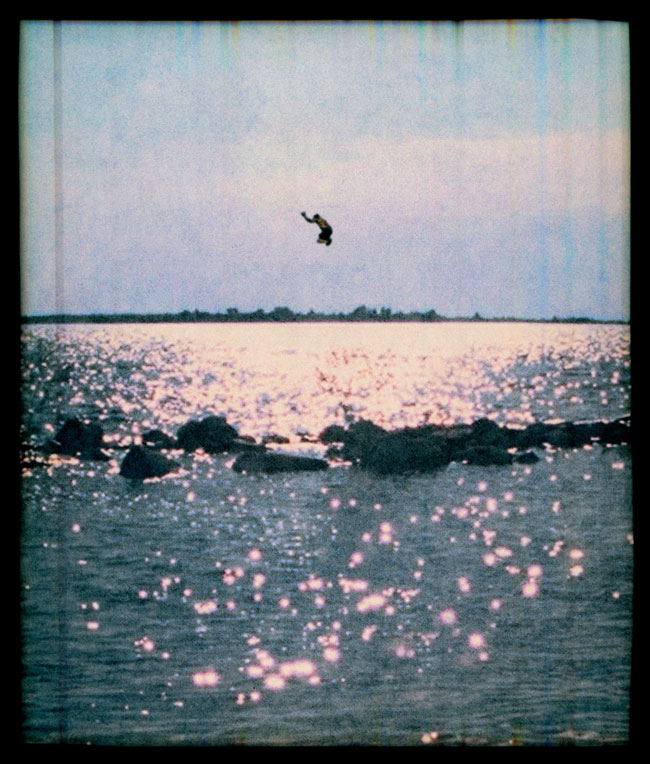

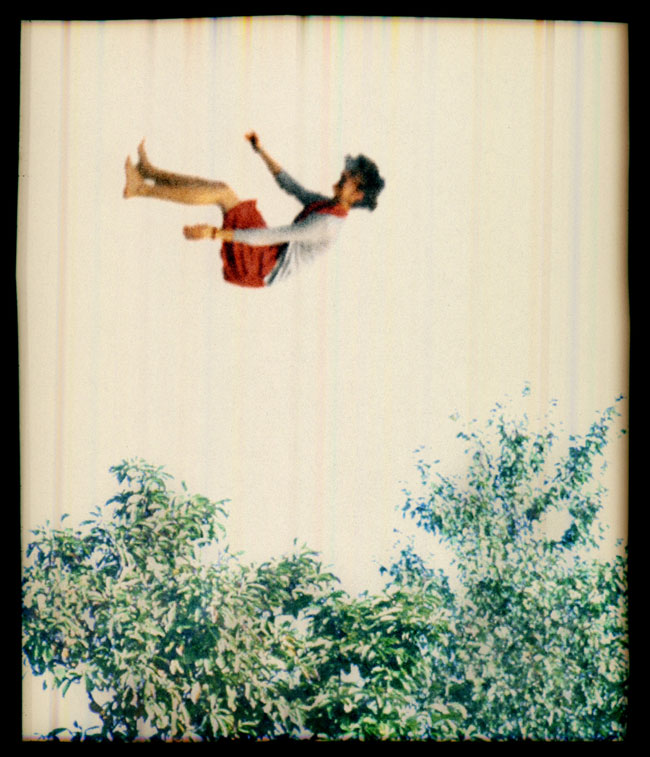

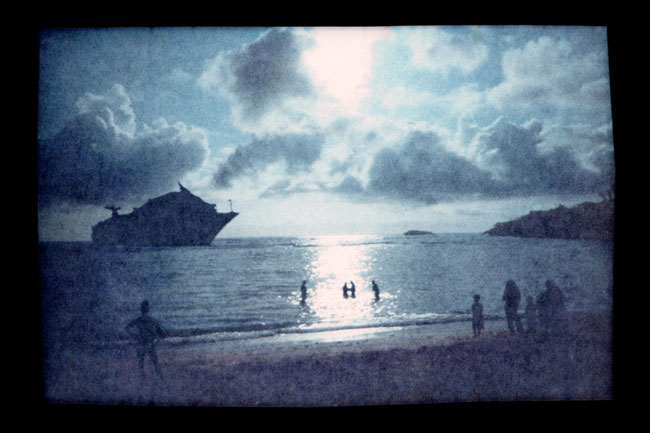

Between plummeting and floating, we’re cut loose from the earth but still part of the world. Elijah Gowin’s images of bodies suspended combine traditional photography with new technology to illustrate the tranquility and the fear of falling.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

How do you make these photographs?

Technically the pictures are compiled in Photoshop so that the figures that are falling and the backgrounds are from different places. I’d also thought about combining technology and getting away from the darkroom, but still honoring elements of the craft. To take something from the history of photography and bring it into the 21st century.

They look blurry and papery and scarred because the pieces of the paper image, which have little bits of pulp, when they’re scanned those pieces of pulp [are visible] as well. So you see the distress and blurriness of the paper as well as the image. Because I hand-cut the image, the funny shapes on the edges stay, but on the scanner they fight it out and start to get these stripes and bars—the scars and interaction between the old and new technology. It’s just like old people meeting young people—there’s miscommunication. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, © copyright Elijah Gowin, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

Why did you choose to show people jumping and falling within landscape?

I wanted to talk about an anxious feeling we have about a landscape. I wanted to make a psychological landscape that has us in it and is a reference to our humanism. Even if you live on the island of Manhattan, that island-ness is very present. We’re dislocated from it sometimes, but it’s out of our control, like when the power grid failed a while back. Those kinds of things wake us up to how we’re really not in control in the end.

How are falling and floating related to that question of control?

Floating can be a very nice release of responsibility. Some people go to a spa to feel that—there’s a peacefulness and meditative-ness to some of the solitary figures floating in the water. But some in the water have anguish. Both falling and floating can be peaceful gestures, but they can be anxious gestures. Some people given the proposition of falling would try to right themselves and struggle against it.

Is there also a sort of death fear involved too?

There is an impending doom in some of these. They’re not dark, they’re colorful, but there’s certainly an anxiety that is nearer than it used to be.

Well, as someone who lived in New York City on Sept. 11, 2001, I can’t really look at images of people falling and not think about that event.

A falling person does seem ominous and that’s why I didn’t want to add buildings or anything. The landscape is an escape; it’s a relief valve. The landscape is a balance between things that could be corrupted and the natural—we’ve gone wrong and the landscape is the way out. It has the answer of where we went wrong.

Is there a way in which these subjects are both part of the earth and separate?

They are kind of dropped in. People say, you know, “I want to get back to nature,” and there’s a quote by Frederick Summer—when people say that he answers, “I wonder where they could have been.” The figures do seem kind of alien in a way and kind of dropped in they’re trying to blend in.

Didn’t you exhibit the falling and floating pictures alongside some of your father Emmet Gowin’s work?

Yeah, we had a show outside of Boston where he had had some landscape pictures including nuclear sites and other aerial sites that show some of our misdeeds. From the air you see some of the things we try to hide. Our work is different, but I guess the issues with landscapes have a kind of similar tone in that they were somewhat cautionary.