Bolinas

Rachel Barrett’s series takes place in the northern California community of the same name that’s known for being reclusive (residents tear down highway markers), and for providing the backdrop to Richard Brautigan’s “In Watermelon Sugar.” (Some images NSFW)

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

How did the project begin? Why Bolinas?

I first learned of Bolinas through Jana, my closest friend whom I have known nearly my entire life. About two years ago, she and seven other women, some of whom I have also known for many years, embarked upon the experience of sharing a home there. When they got the house, she told me of the history of Bolinas, the way of life that had persisted over so many decades, and the intense beauty of the landscape. I wanted to go, not with a dedicated body of work in mind but to simply experience it myself, though as always with my camera in hand. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

I made my first visit in July 2009, which lasted for only a day and a half. But in that short time I created what I felt was some of the most exciting work I had ever made, and I decided at that point that I would make Bolinas the place. I believed there was a great deal to investigate and explore in this place and within myself. It was over many months and through the process of creating the work that the ideas within the series—of what Bolinas stands for and represents within the larger context of the current social landscape in America—came together, and began to come through in the photographs.

Bolinas is known for being an isolated community—street signs are handmade, highway markers are torn down. How did you gain access?

There are many misconceptions about Bolinas. I was warned by many who know only of its notoriously reclusive reputation that the community would be very difficult to broach and that I and my camera would not be welcomed. I think any person and/or community can be tricky to gain access to when it comes to making photographs about them. People are wary of the device, uncertain of how they will be depicted. I have been asked so many times, “What are those pictures for?” As if I am up to no good.

Many years of practice informed me in how to approach this situation. I have respect for Bolinas and the people there and wanted to make sure that came across, working diligently to engage with everyone I came upon and reach out to the community in a manner they would appreciate. Fortunately, time and repeated extended stays enabled me to cultivate relationships and create a presence so that people recognized and knew me, and not just allowed me to make my work but supported and encouraged my exploration.

Everyone has a story and usually wants to share it, but usually on their own terms. I quickly learned not to ask if I could “take” someone’s picture—because they wanted to know why I wanted to take something from them (usually a piece of their soul)—and to instead ask if I could “make” a photograph “with” them. That slight change in language opened up so many moments, and helped me realize how the process of creating this work is intrinsically about the shared experience.

It is true, though, yes, that highway markers are torn down, but I would not say that was done to remain isolated but rather in an effort to preserve the way of life. That street signs are handmade symbolizes the deeply personal ties the members of the community have with one another, and how important it is to maintain the lifestyle they have worked so hard to cultivate and create. Over the last many decades, from what I understand, they have succeeded incredibly well. Things are the same, different in ways but so much the same. This is something I hope to express in my work.

Did your views on the off-the-grid movement change after spending time there?

Much changed after spending time in Bolinas. As far as the content of the work, I did not set out with any specific ideas of I would shoot. I embarked upon “Bolinas” like an exploration, open to whatever I would discover and would be revealed to me. It was important that I allowed the place itself to be what informed how the work was made and what the photographs would be of. As a photographer, having the time to just look, see, and respond with a camera is a gift, a luxury. It provided me a sense of freedom, and I shot instinctively and intuitively, unencumbered by any critical theory or ideology. Looking back, I think it is significant that much of my early work was of the land itself, the rawness of the earth, the textures found in the woods, on the beaches and in the sea. The more time I have spent out there the more intimate the images have become, as I have developed a deeper sense of what this work can say, and as I have grown less awed by the way things look and what this town is all about as it shifted from being something new and different into the everyday.

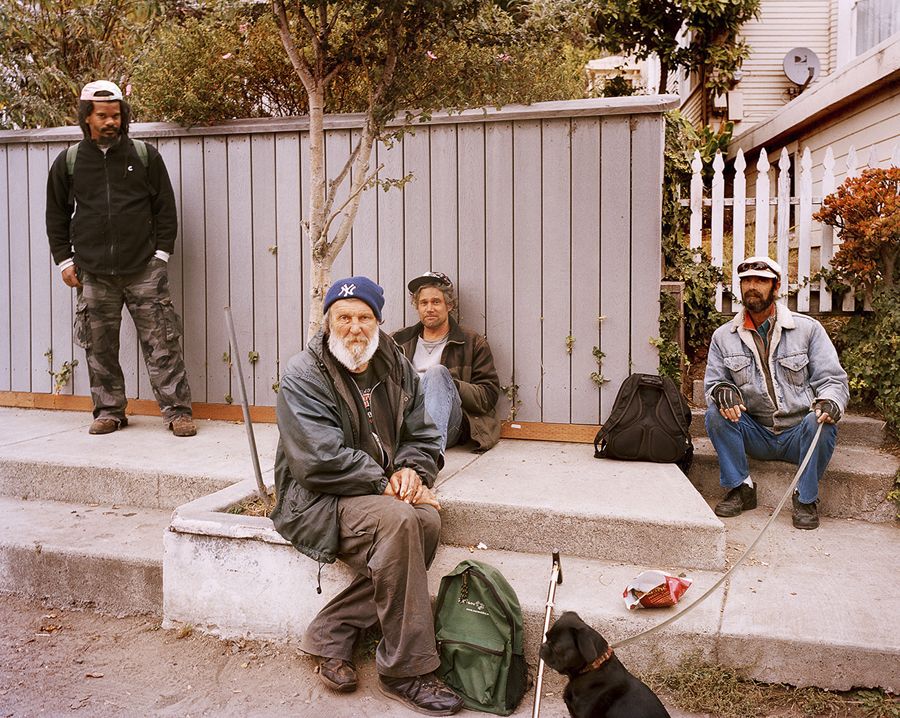

Many of the pictures in the series are idyllic: The people are beautiful, the nature’s full of lyrical patterns. Was there also hardship on view?

Of course there is hardship—there is in any town no matter how big or small, how mainstream or counter-culture. The hardship takes on various forms: Some are dealing with substance abuse, many can not keep up financially, others sink into despair after decades of living such a solitary and at times isolated existence. I was at first wary to turn my camera to this, because I was not making a documentary series, this is not photojournalism. Making these photographs was then and continues to be about self-expression, creating something born out of my own personal experience and relationship to the people and the place.

Bolinas has had a tremendous impact on me personally, both my art-making practice and how I live my everyday life. When I began going out there, I was at a point where I desperately needed a break from a decade of life in New York City. I needed to give myself some time and space to heal my body, mind, and spirit. There is something about the energy in Bolinas, which has a strong and nourishing force. Perhaps that it a result of its geology—Bo is on the Pacific Plate moving north at an average of one inch per year. Truly, once you cross over a certain point off Highway One you can feel it, hanging heavy in the air. The earth and the sea, the sun and the moon are powerful, beautiful, and seductive, and I think the photographs from my first many trips there are true to my state of mind, that I was falling in love with this place.

What are you working on now?

I am still working on “Bolinas.” I believe this work requires the passage of time, so that the ideas that I am saying this place represents and is about can come through visually in my images. I was back there in October for nearly two weeks and will return again in early 2011. With these new photographs I really turned my attention inwards, into this home of my friends. I want to investigate further the realities of living a communal life, and to create more of a narrative in the series, albeit an abstract one. As well, I am committed to taking a deeper look at the life of young, organic farmers, and so spent a good amount of time back on Gospel Flats farm, run by close friends of the house, the son, daughter-in-law, and nephew of the couple who started it.

I am also still working on another ongoing series called Josiah’s Farm, which I began in the summer of 2006. This work is a sort of companion to “Bolinas,” also with an emphasis on back-to-the-land ideologies. This series focuses on a group of young men, born and raised Mennonites in the Shenandoah Valley, who moved to New York City about 10 years ago and have been cultivating a large property in the Catskills in upstate New York to get back to their roots and the way of life they were bred for.