Breakthrew

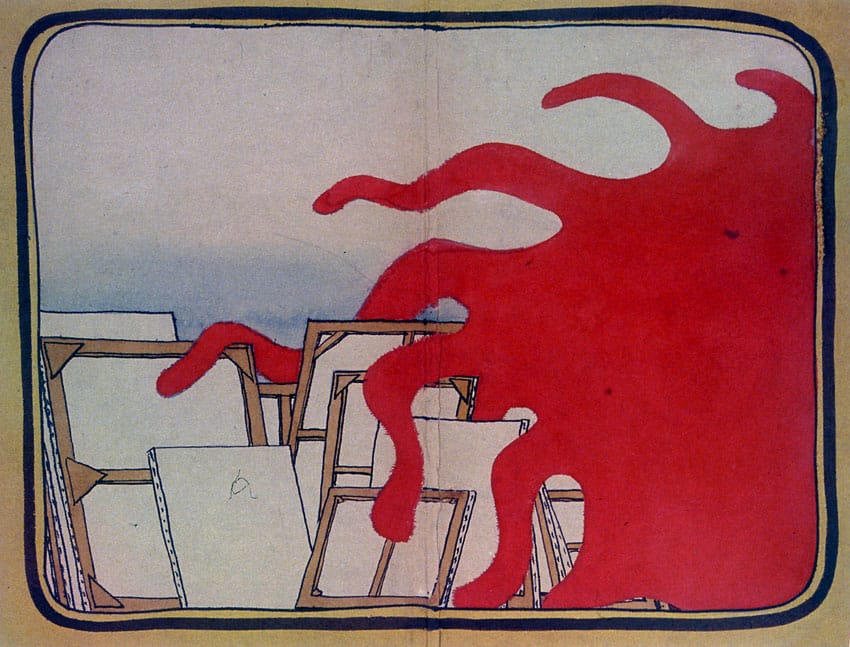

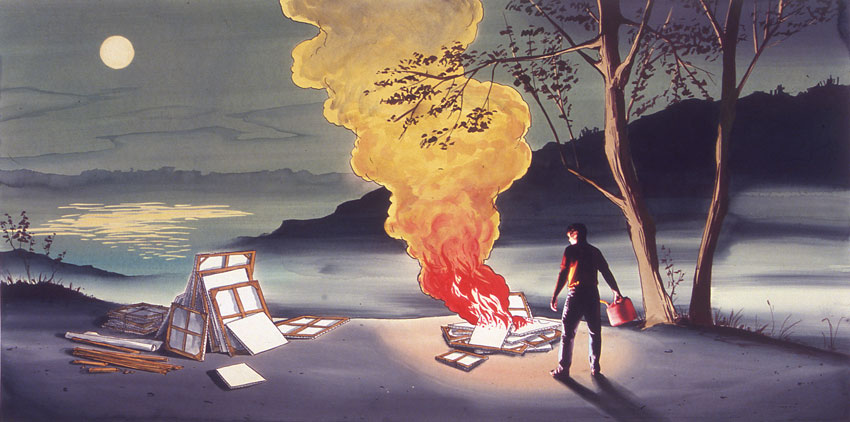

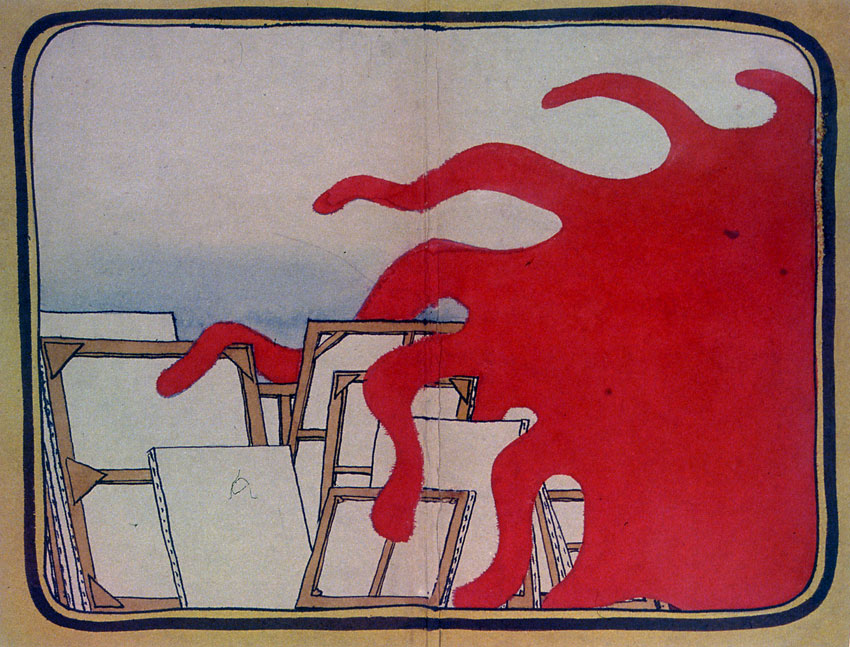

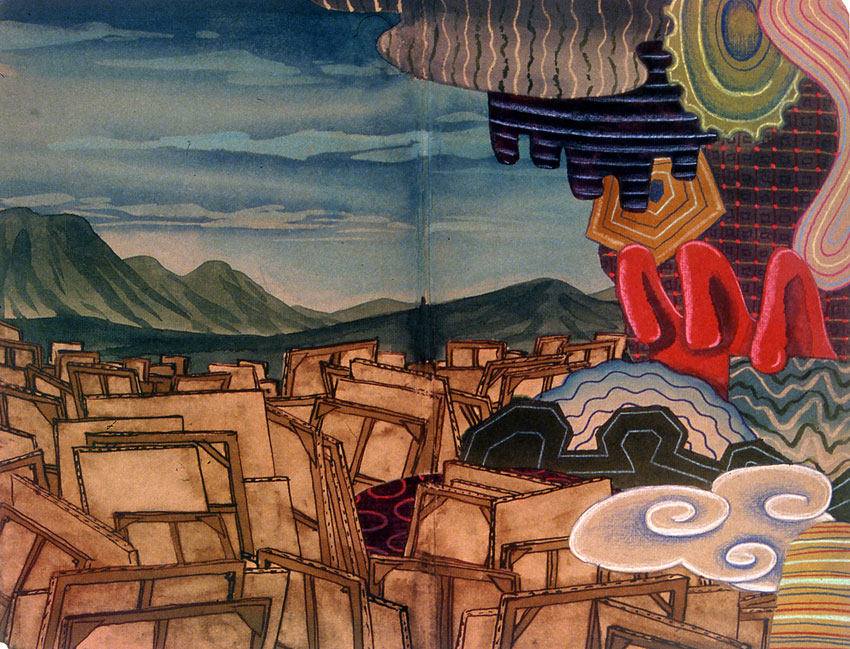

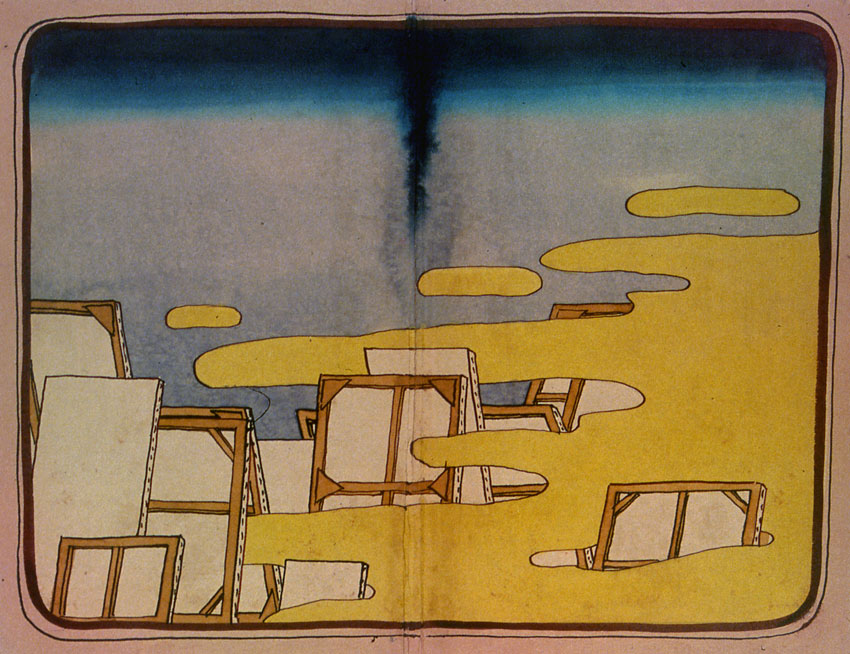

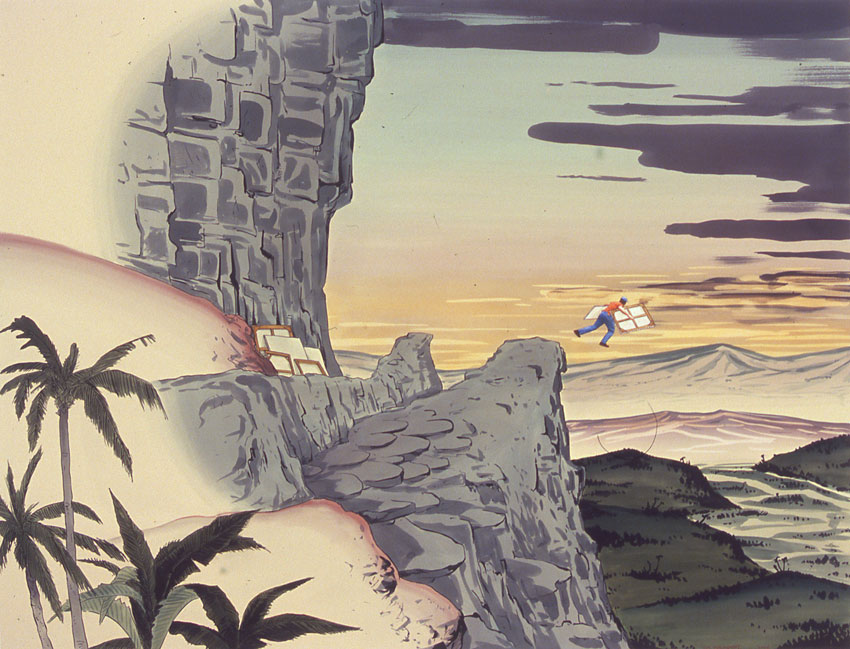

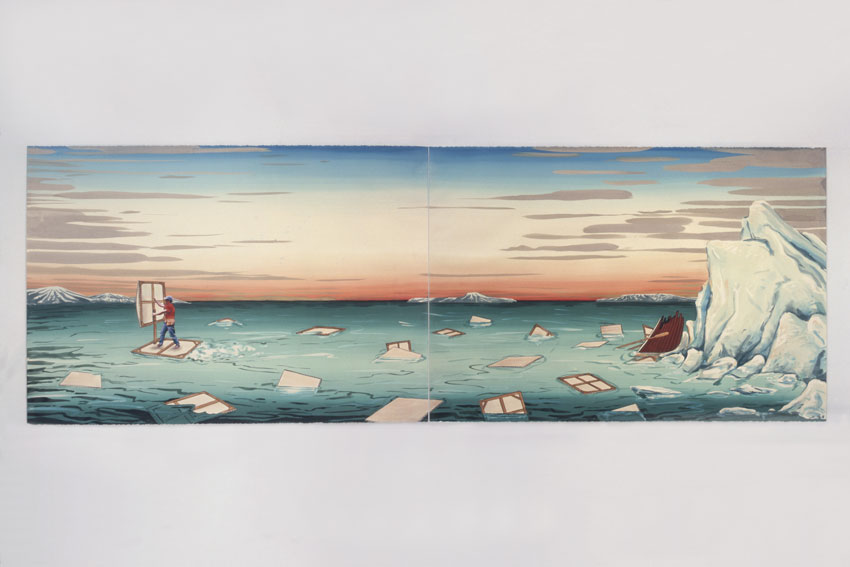

Can warm colors and personal crisis be political? Can drawings cure artist's block? Tom Burckhardt burns, drowns, and mourns the canvas—but never paints on it.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

This show is primarily on ink and paper. Are you typically a painter?

I don’t know if I can say that anymore. That’s where I come from, and for probably 15 or 20 years I was definitely a painter. I still make paintings but I’m flying off in a lot of different directions. At the very least, it all ends up being about painting. Continue reading ↓

Tom Burckhardt's show, Breakthrew, was recently on view at Tibor de Nagy. All images are © Tom Burckhardt and appear courtesy Tibor de Nagy Gallery, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

Why do these drawings depict canvases being destroyed or overtaken?

It would have to be traced back to my previous show, which was at Caren Golden. For that show, I made a studio out of cardboard. There was a narrative buried in it about an artist who is blocked and who can’t find the inspiration to work any longer. As I was painting, I had a moment of feeling uninspired. I found that moment interesting. Rather than fret about it, or become overtaken by it, I wanted to turn it around. I took this moment of not knowing what to do and I laid out a project where I knew exactly what I had to do from morning ‘til night. I’m meandering when I’m painting, and it’s either happening or it’s not, but it’s really hard to have your work cut out for you in the same way as it was for me with [the cardboard] project.

Why follow the cardboard studio with these drawings?

I used to be a very consistent artist. Now things are a lot harder because when I finish something I’m not really sure where to go from there. Although the cardboard studio was very fruitful, I didn’t want to be “the cardboard artist.” That was a break from what I was doing before. The cardboard project put an end to any of my audience’s expectations and I didn’t get the sense that people were disappointed. I picked up the thread by doing these works on paper for [Breakthrew] at Tibor.

So the artist and the canvas became figures in your art?

The strange thing is, I’ve never worked on canvas. It’s sort of a shorthand for the world of painting. I’d been doing work where I’d insert myself into an abstract painting and [it would look] as if I had been working on the paintings. I combined this [idea] with the central character of the studio—the blank canvas.

I like the character of the artist who has failed. The descent of the artist who has given up has become the greatest excuse to make all this work. There are very opposite things within the work. You get [both] pathetic desperation and a certain sense of beauty and optimism. Although there’s a narrative that’s very sad; hopefully, you get an enriching feeling from the work.

There does seem to be an overall optimism in this work. You get the sense that the perils you depict are just a part of life.

It’s not a sad show. It’s kind of funny—it’s black humor. The person who is really behind the show is Buster Keaton. He’s a sad sack and a bit of a loser, but you really love him anyway.

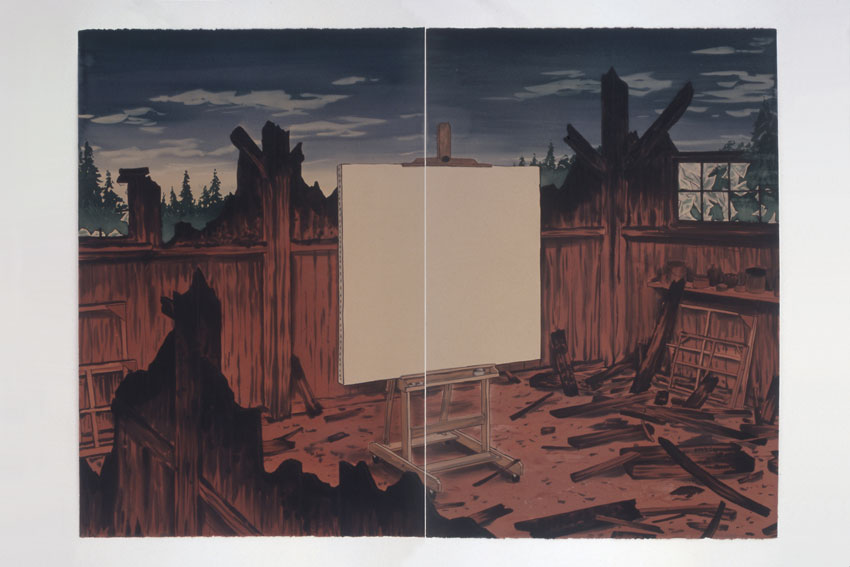

Why have you used a digital image of yourself, why not draw yourself?

This goes back to the work’s split in tone. There’s a disjunction and the character [does] not quite fit in the stylized landscape. That makes it theatrical and keeps it from being too depressing. The technique of the landscapes is brought to the surface when you put the photographic image inside them.

Why place this small person with a small battle on a very large landscape?

A lot of the source material, or the landscape parts are influenced by Japanese prints, called Meiji-era war prints, that were produced around 1890 and 1900. They mark the start of the imperial Japanese invasions of Korea, Taiwan, and Northern China. They’re propaganda prints and they often depict images of soldiers doing brutal things within very beautiful, classic landscapes. In some cases, they’re not actually depicting something terrible, but their historical implications are terrible.

You are describing a sense of disunity; however, your drawings come across as somewhat resolute. Did you intend to depict disunity in this work?

I’m not sure why the background of this artwork is important, since the story I’m telling is kind of personal. But I find those prints fascinating to look at because of the jarring disjuncture between what’s happening with the figures [in the drawings] and this beautiful landscape. They feel apropos to what’s happening now. The way our country conducts itself internationally reflects the same hubris that is [present in the Meiji] prints.

Can paintings that are bright and colorful and humorous also be political? Is it a problem if something just isn’t political?

I wonder about the place of politics in art. I’m not interested in political art that lays out certain issues baldly. There’s a sense that this character feels despondent and powerless in the world of painting or art making and that’s totally how I feel politically.

You can put a canvas somewhere, you can light it on fire, but at the end of the day everything is bigger than the figure.

Although I feel very invested in [my work] I am mocking the self-importance of art making.

Your work is humorous. Do you feel this helps your work to be more directly appealing and accessible?

I’ve always been concerned with work that felt generous. Going to look at art shows or museums over the years, I’ve always had a problem with work that looks over-intellectualized—work that plays a game of enticement and tries to reveal as little as possible. It’s like a velvet rope at a dance club. It’s art that’s aloof and mysterious and that’s not giving anything up. I’m interested in work that comes out to greet you.