Days of the Dead

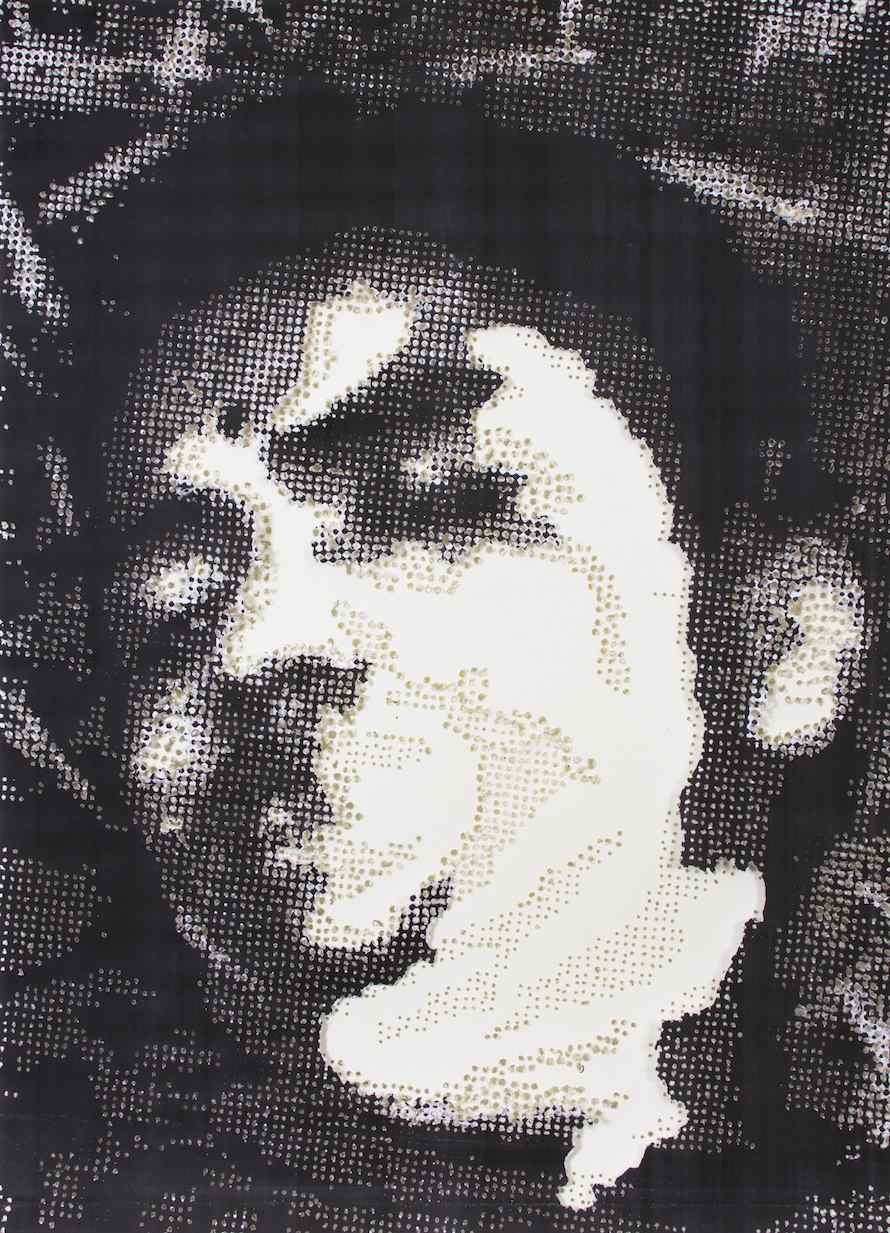

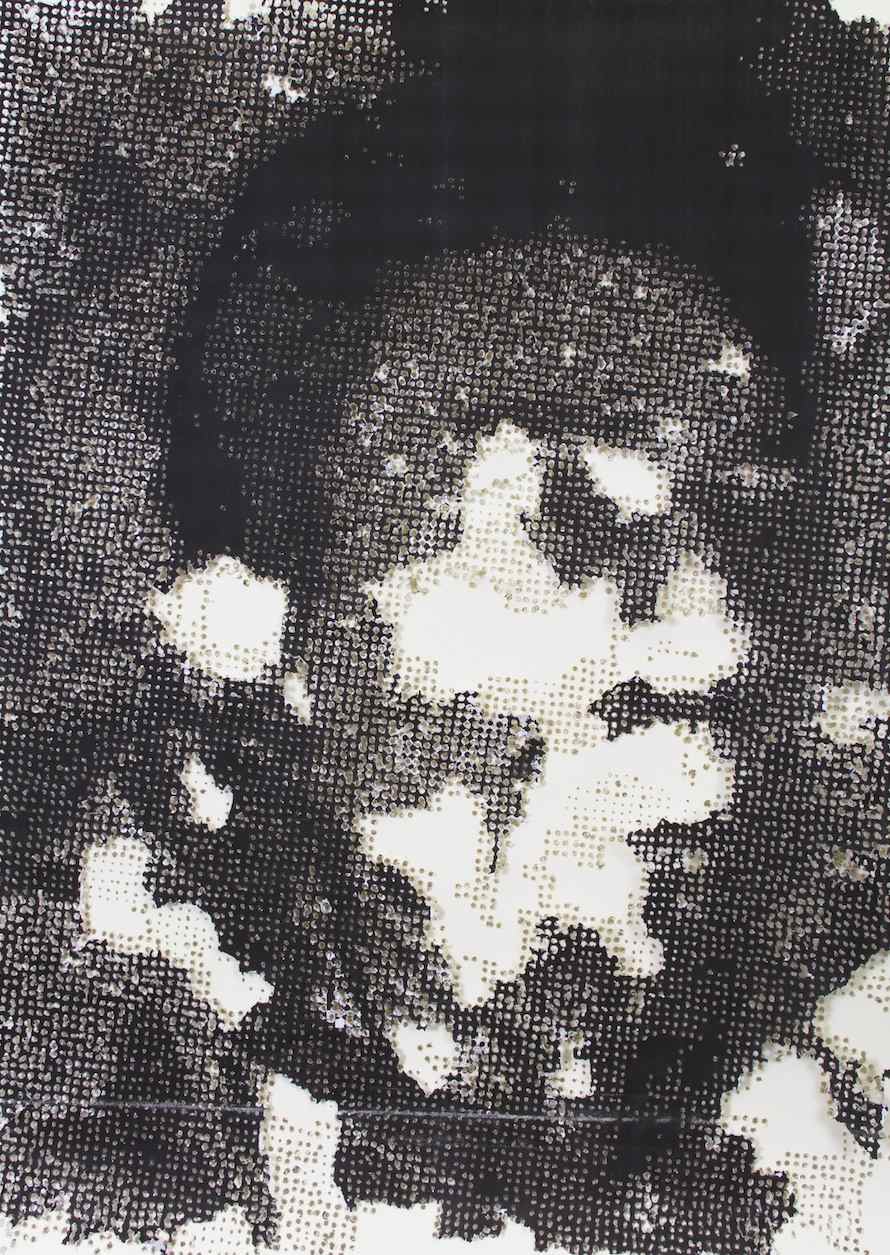

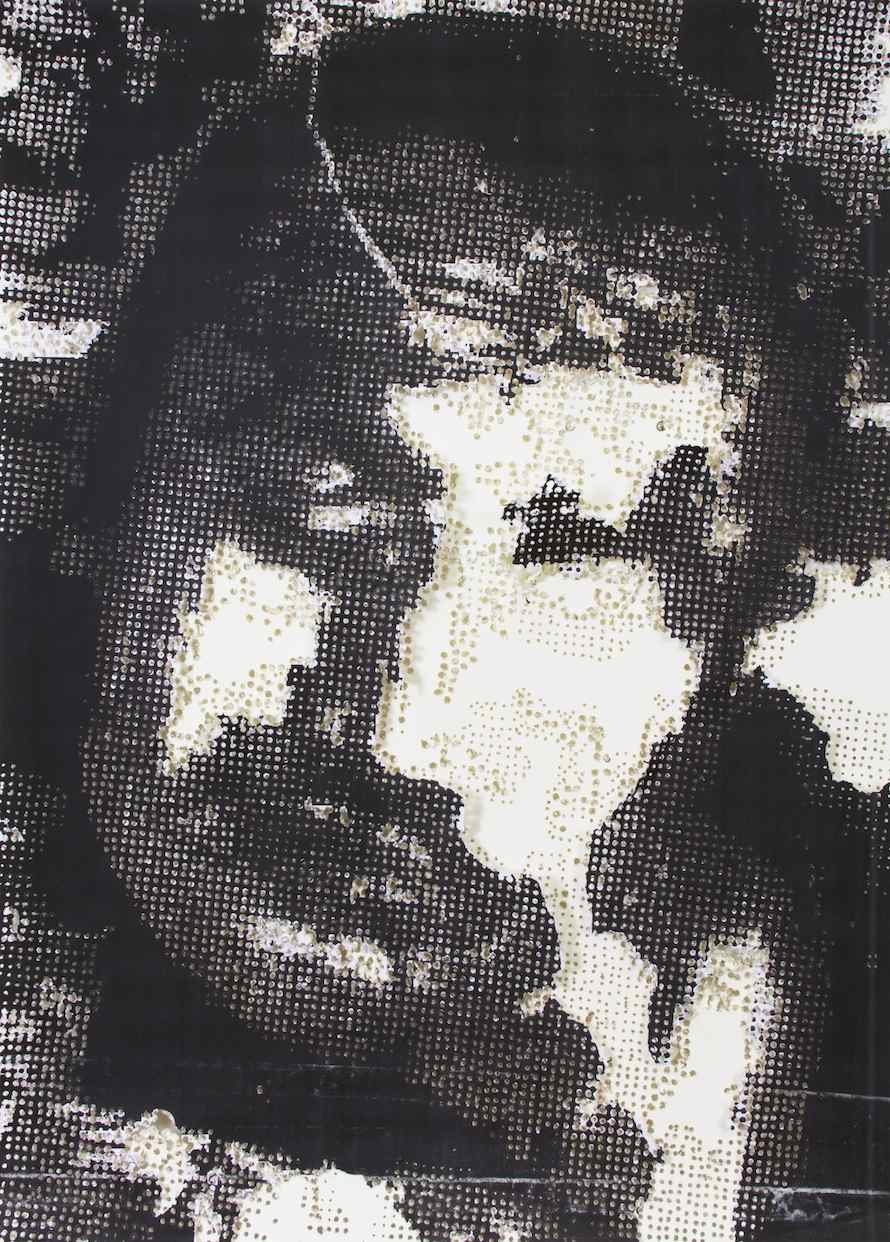

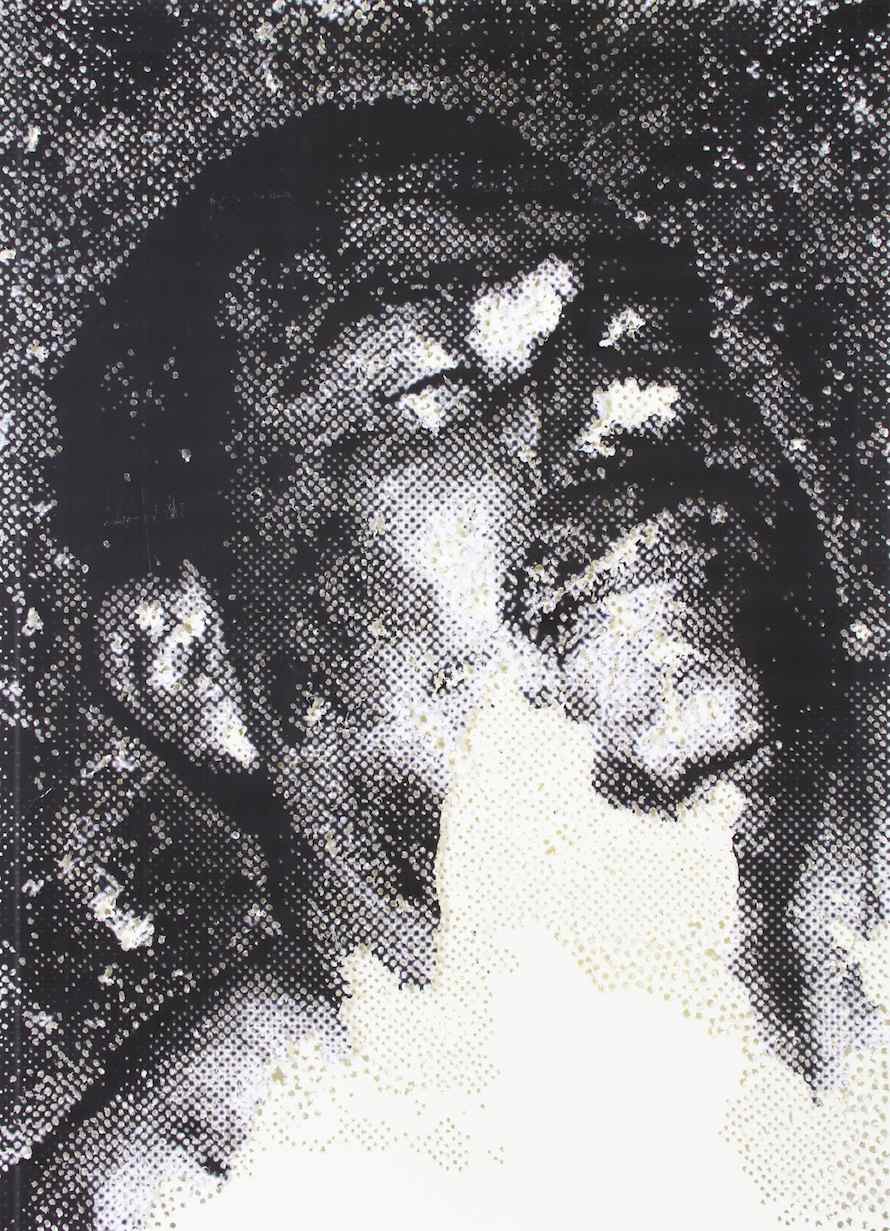

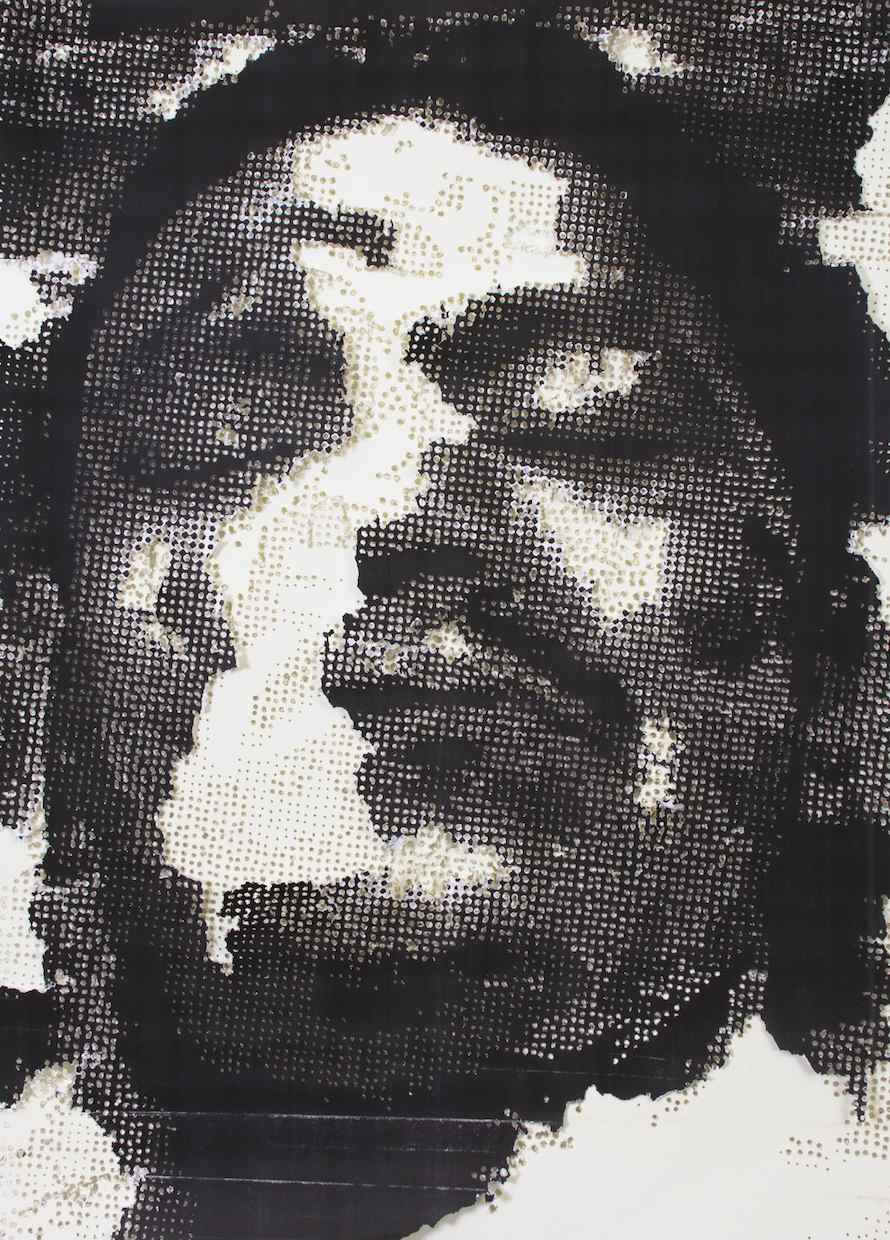

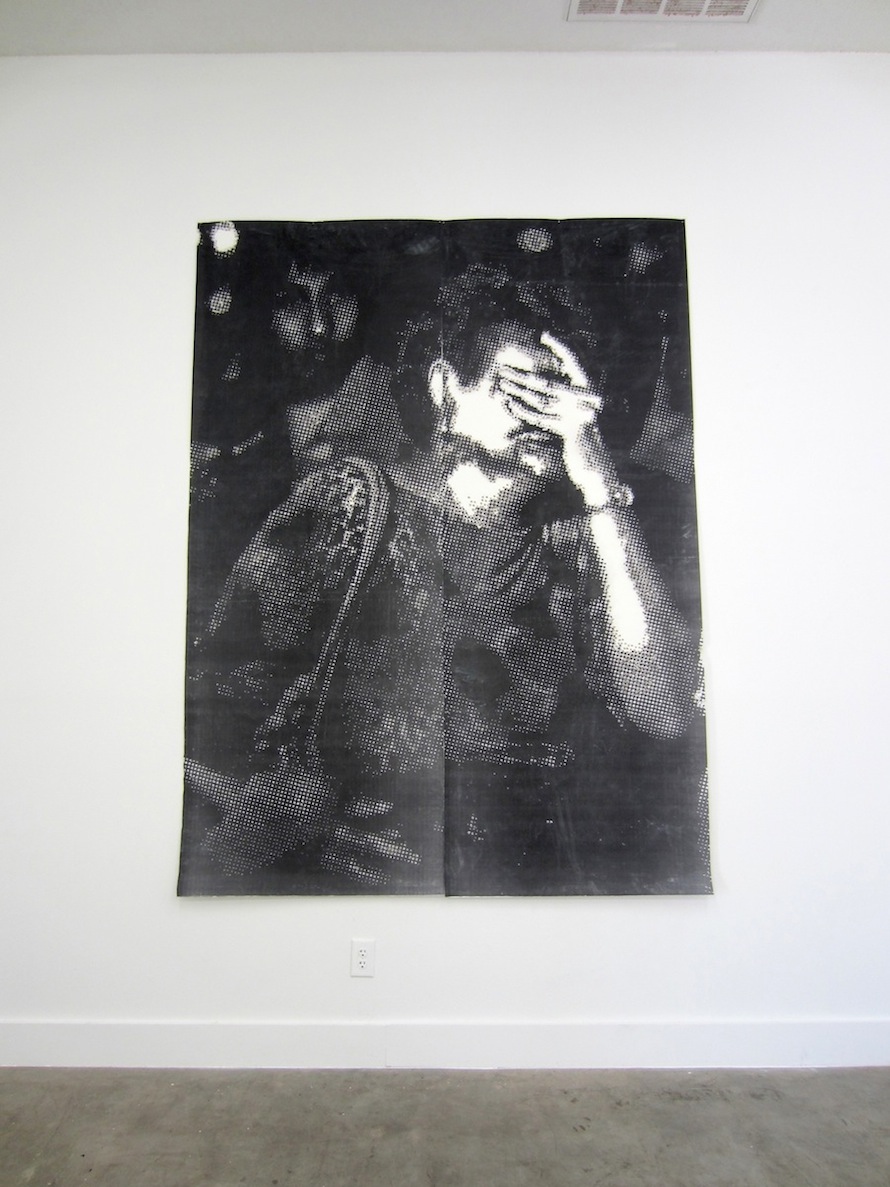

Large-scale, hand-drilled portraits—where pixels are drilled from enormous blown-up photographs—of people killed in Mexico's drug wars.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

The Morning News: Explain what you mean by a portrait that’s “hand-drilled?”

Miguel Aragón: That is simply the process I am using to create these pieces. I begin by cropping and blowing up the face of one of the many casualties of the drug wars in Mexico; this allows me to “enhance” the pixels of the photograph. I then make a stack of different kinds of paper, usually about five pieces of white cotton or rag paper, five pieces of black tar paper (commonly used for roofing), with the blown up Xerox print-out on top. Then I attach this stack to a piece of drywall and begin making the piece by drilling each individual halftone one at a time using a hand drill and different size drill bits. The end result is a multitude of pieces of the same image, which I use in different configurations during the exhibition of my work. Continue reading ↓

“New Works by Miguel Aragón” was recently on view at Tiny Park, Austin. “Bodies for Billions” will show at Rogue Gallery and Art Center, Medford, Ore., July 11 through Aug. 29, 2014. All images used with permission, copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

TMN: Have any families of the portrayed seen your portraits?

MA: I’m not aware of any of the families having seen my work. When I began collecting these images from the media, not all the information was provided. Sometimes they wouldn’t name the casualty at hand, either from a lack of information or some kind of censorship from the newspapers/blogs. This is why I felt compelled to make work about these events. They started to become “numbers” rather than human beings. I’m not differentiating cartel members from innocent bystanders—to me it’s not about blaming somebody but more about reflecting on the fact that the country is losing it’s citizens, somebody’s father, brother, son, etc.

I haven’t had the chance to display my work back home unfortunately, not even in El Paso. I’m hoping that an opportunity will present itself soon. But my family, several friends and people I’ve met from Juárez and other parts of Mexico have seen it and they all have responded really well to the work. I think they relate and understand what it is I’m trying to do.

TMN: What obligations do you obey as an artist?

MA: I have to be true to my beliefs. I can’t make work I don’t believe in. And I am always aware of the viewer. Because of the work I make, I know I have to be very careful in what I say or make, not to be “safe” but to be honest and respectful of the subject matter. It’s something that hits me personally. I’ve been fortunate that my family, friends, and I have been for the most part on the outside of these events. But it has affected my city and the way we relate to it because of the violence. I am trying to reflect how “we” continue to try to live in a world that is full of violence and uncertainty.

TMN: The Mexican media is pretty graphic about covering the drug wars. To an American reader, it can be startling to see the front pages. You often work from media images—is this inspiring? Disturbing?

MA: Both, actually. I began collecting images from the Diario de Juárez well before an official “war on drugs” was declared in 2006. Mainly because I noticed a pattern—back then it was only local news, and it’s what I called “behind closed doors violence,” meaning the shootings didn’t happen in broad daylight or outside on the streets, but rather the police would find bodies buried, encased in cement or inside car trunks. The images were pretty crude for a reputable local newspaper; usually those kinds of images are reserved for the “yellow press” or tabloids. In Mexico, though, we’re more accustomed to these kinds of images than in other parts of the world, mainly because it’s part of our culture. But knowing that my viewers would be from all over the world, or rather I wanted to reach as many people as possible, I knew I couldn’t use the images in their original form. Therefore, I use distortion and erasure as part of the creative process, to tie the idea with the subject matter. I feel that by using these languages the viewers will spend more time with the images, achieving a greater impact.

Nobody wants to see a violent image. Most people will spend a couple of seconds and turn away. I needed a different approach, by stripping away all the color, editing the composition. I’m making the images a bit ambiguous, forcing the viewer to spend time with the piece and look for answers.

After a while I get desensitized to these images, something I was aware would happen. But I still can’t get over it. I can’t come to terms with the fact that people in Mexico have to force themselves to ignore these images, that this is now the norm and not an anomaly. That’s why I feel the need to make these bodies of work. We have to change the current perspective of the country and of its people. It’s really disturbing to see what one human being can do to another without a shred of remorse.

TMN: Describe a typical work day.

MA: Well, that varies a lot actually. I haven’t been able to get what you’d call a routine. I’ve been in New York for about a year now, but things are still a bit unstable. Mostly because I’m still getting settled in my new job, and I’ve been traveling a lot this past month. However, when I get lucky and find myself with some time for the studio, I usually begin by arriving around 8:30 to 9:00 a.m. and working all day without interruptions till about 5 p.m. After that I usually go out to eat, either around my studio or somewhere in Manhattan, then walk for a couple of hours. Sometimes I go out to galleries, or just walk around different parts of the city.

For the last few months I’ve been working on several pieces of the “hand-drilled” body of work for a couple of solo shows—the one currently installed at Tiny Park in Austin, and another one at Rogue Gallery and Art Center in Medford, Ore., which will open on July 11th.

TMN: When are you most at peace?

MA: I’m really enjoying living in New York. For my commute to work I have to take the ferry, which is really nice and peaceful, but when I’m most at peace is when I take a walk. I just put my headphones on, crank the volume, and wander aimlessly; I’m able to clear my head and enjoy the moment. It’s something I’ve been doing for the past five years. Before I moved to Austin in 2009, I was always driving, and when I got there I didn’t own a car anymore, so I had to rely on public transportation and biking or walking. I never knew I would like walking so much. I never got into biking (Austin has a big biking community) so I’d instead just walk all over town, enjoying the views and clearing my head.