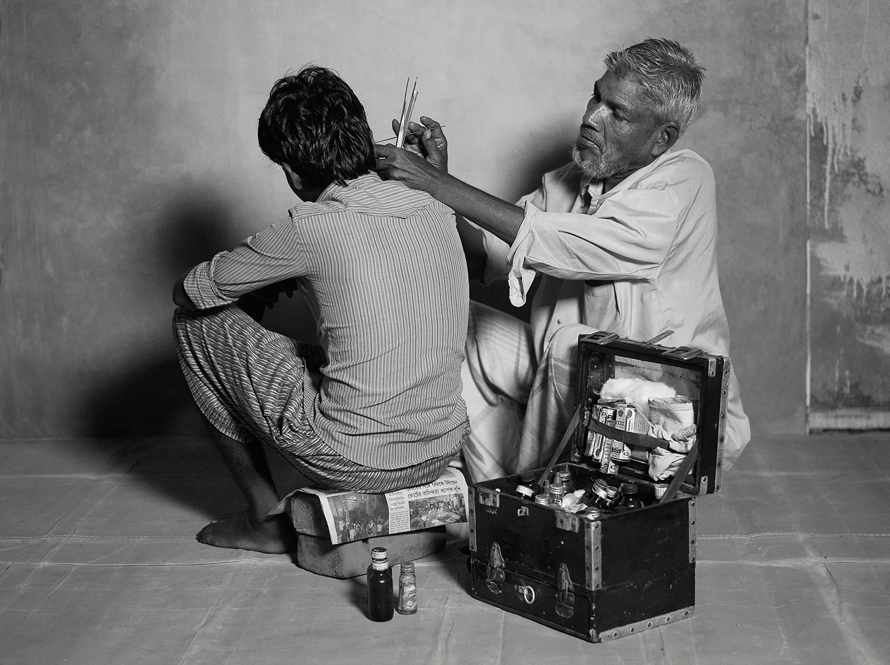

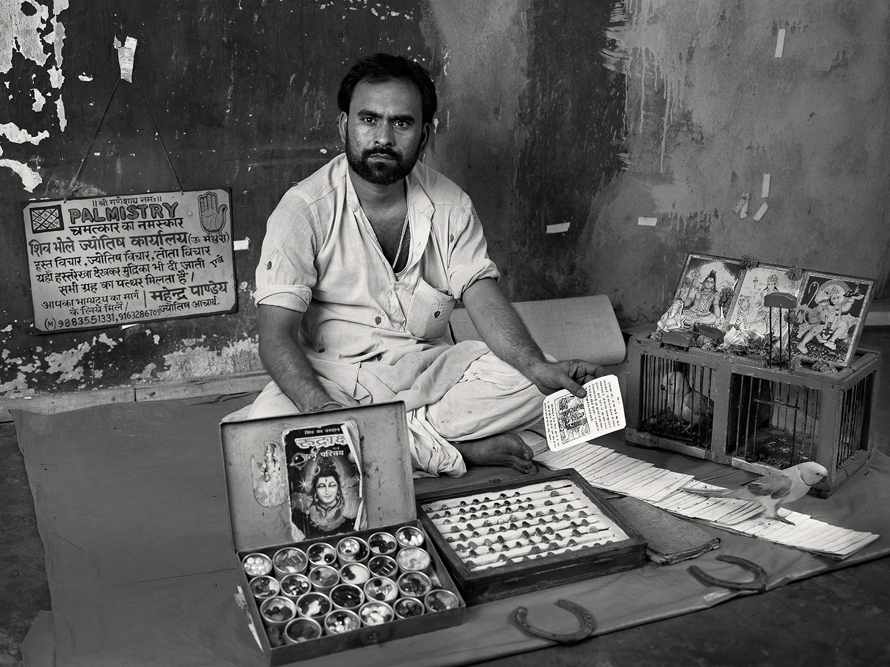

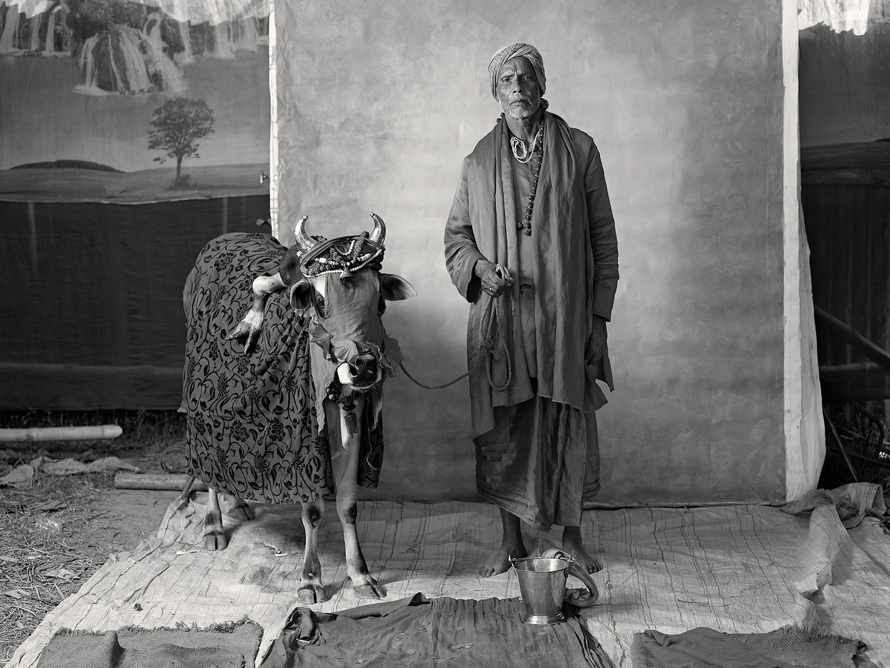

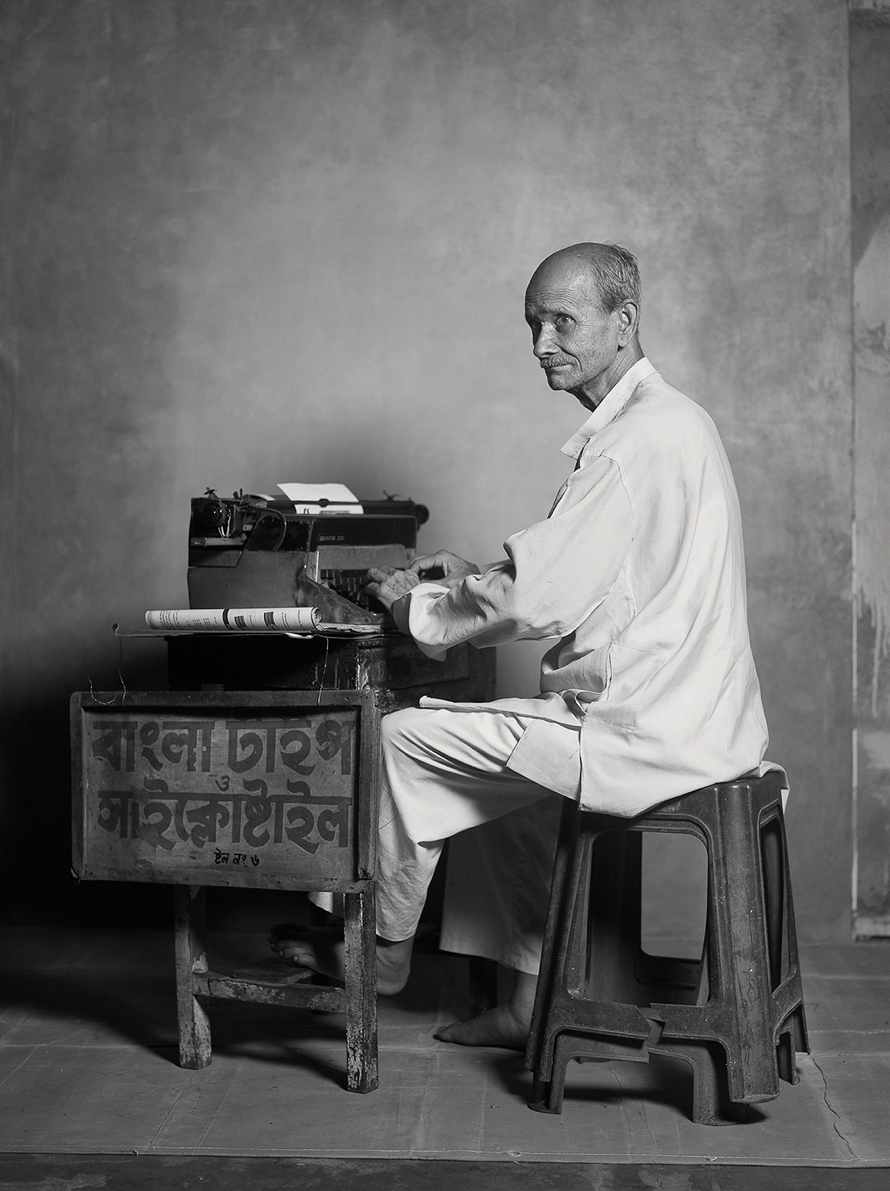

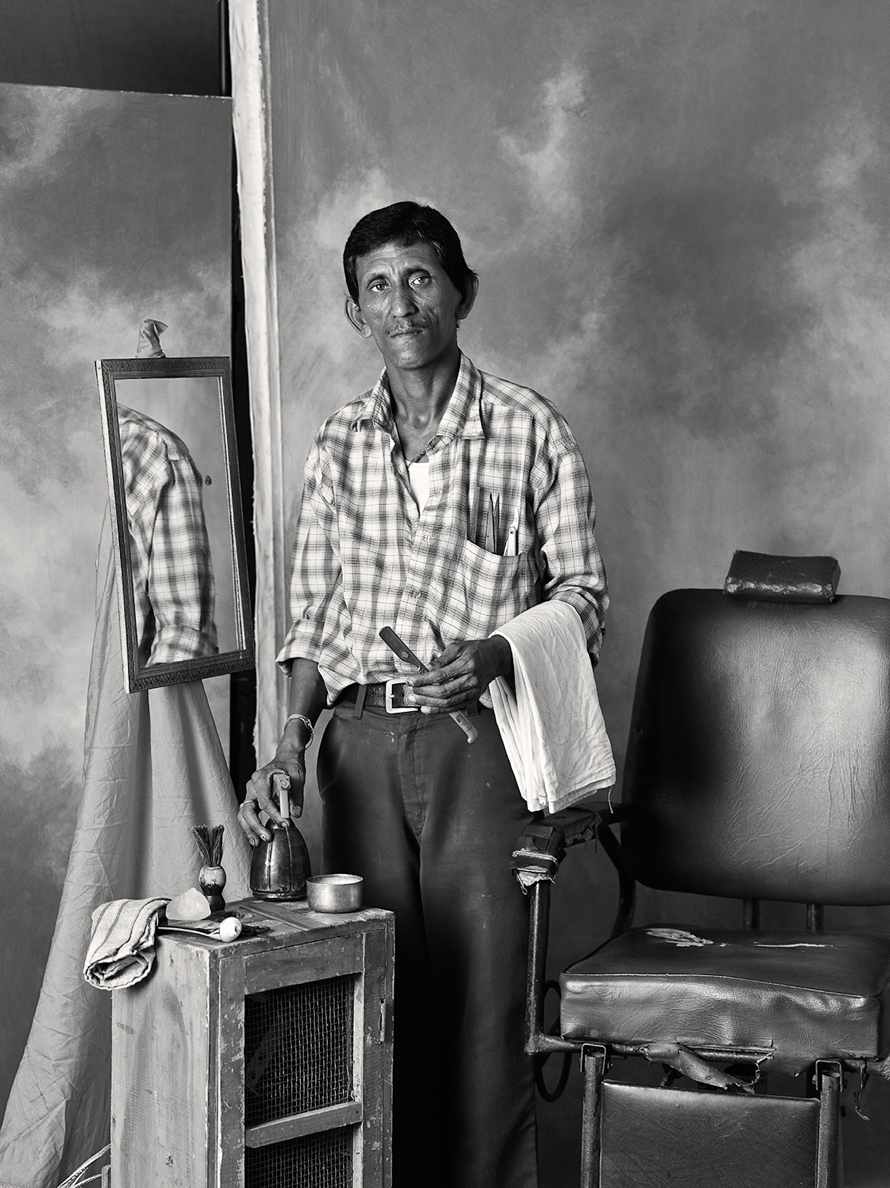

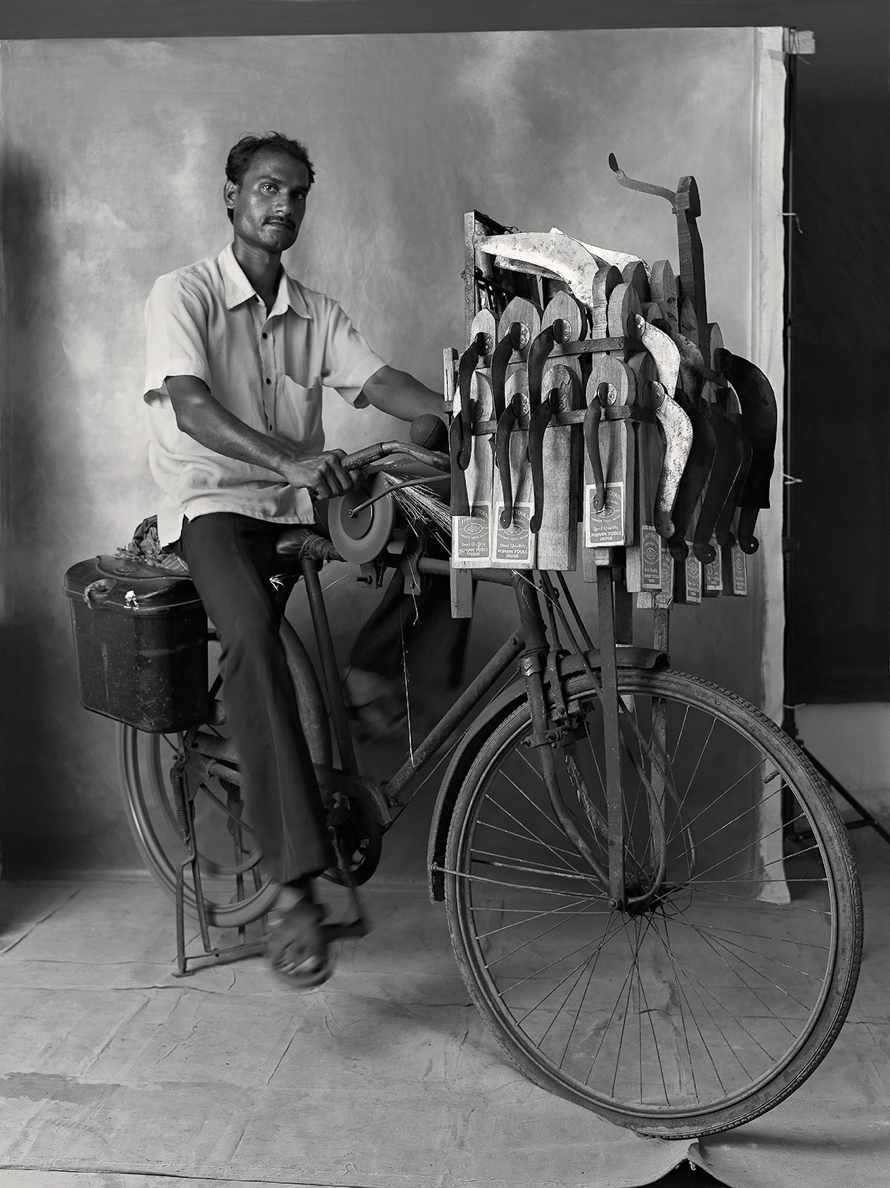

Everything-Wallahs

Ear cleaners, knife grinders, street-side barbers—portraits of Indian tradesmen who maintain caste-prescribed professions.

Interview by Karolle Rabarison

The Morning News: How do you explain this series to your subjects?

Supranav Dash: I am always upfront in my approach, explaining to the tradesmen why this project is so important for me. Almost everyone I speak to realize their profession will not be the same 20 years from now, but few decide to let go of their inhibitions and agree to be photographed. India is undergoing drastic socio-economic change. The analog trades that never updated or changed themselves over the centuries will not be able to resist the technological advances of modernity and will eventually fade out. This will impact every single person one way or another. I explain to the tradesmen why it’s so important, for the sake of preservation, from the social and historical point of view, to document their marginalized trades. Continue reading ↓

Photos from Supranav Dash’s ongoing project “Marginal Trades” are on view through Sept. 14, 2013, in the group exhibition “Degrees of Separation” at SVA Gallery. All images used with permission, copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

TMN: You devoted at least five years to studying painting before you shifted focus to photos and launched a career in fashion and editorial photography. What prompted this move?

SD: I have always been in love with the arts and have studied different forms, from fine art painting to the sitar and the tabla. But when I discovered photography, something changed in me, and it soon became my obsession. At first it was just a hobby, but the more I devoted time to it and developed my skill and techniques, the more I wanted to explore the various photographic genres. I started with commercial photography—editorial and fashion—which to this day captivates me. But then as I studied photography in school and learned about the works of the masters—Atget, Penn, and Sander—I changed direction again. I am not opposed to continuing my fashion and editorial work, but as a photographer I do not want to limit my vision. I am first a photographer; genres and tags come second to my creative drive.

TMN: Do you take photos with your mobile camera?

SD: Yes I do, but only for Instagram—as a palette cleanser. It is a way of deviating from my normal approach to photography. With my iPhone, I experiment, break the rules, and create images that are raw and tangible.

TMN: Where does “Marginal Trades” sit in relation to your previous work?

SD: India has been the backdrop for most of my work. I believe in storytelling. In my early work I would distill a certain idea and would go about illustrating it artistically, creating staged tableaux scenarios such as “The Boatman’s Wife” or “In a Hindu Girl’s Life.” Those images are supposed to be slices from real life but in a more editorial context.

With ”Marginal Trades” and the ”New Mothers” series, I started exploring the portraiture genre from a social documentary approach. I wanted to blend my art school knowledge and professional field experience to invest into this massive body of work that could do justice to these dying trade practices.

TMN: You identified Irving Penn as one of the inspirations for this series. He once described the camera as an instrument that is “part Stradivarius, part scalpel.” In what way would you disagree?

SD: Every photographer has their own concepts and notions of what photography and, more importantly, their camera means to them. Penn transformed himself many times as a photographer. I would neither agree nor disagree because that is how Penn himself felt about photography. August Sander, another inspiration of mine, would say, “Nothing seemed to me more appropriate than to project an image of our time with absolute fidelity to nature by means of photography… Let me speak the truth in all honesty about our age and the people of our age.” Sander thought of the camera as capturing an absolute objective truth, whereas Penn thought of it as the artist’s tool. They are neither right nor wrong.