Farce and Sensibility

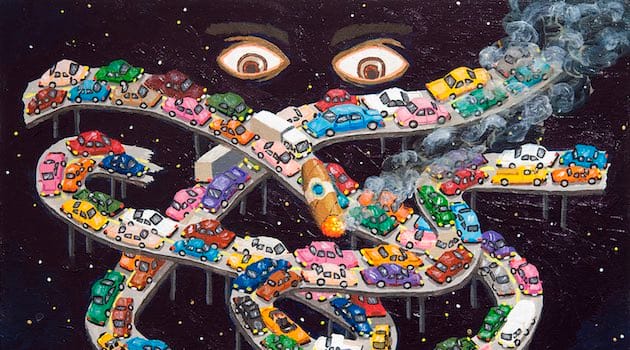

Paintings of peculiar worlds where butterflies sizzle in frying pans. The more you pay attention, the less you’ll understand.

Interview by Karolle Rabarison

The Morning News: I’m intrigued by how you incorporate humor and surprise in your work, both in the images you paint and the language you use to describe each piece. Catchy titles like “A Snake Also Has Muscle Memory” and “Serene Sewer,” for instance, force me to pause and pay attention. Talk us through how you get started with these ideas and images.

Ralph Pugay: It wasn’t until the middle of my graduate school experience that I started to paint. I went to a school that was focused on conversations relating to post-studio and socially engaged practices. At the time, I wasn’t even looking at myself as a painter or looking at painting that seriously. I was, though, interested in artists like Bruce Nauman and John Bock in terms of process. I also really liked how Mike Kelley and Chris Johanson dealt with abject and existential themes. Continue reading ↓

Ralph Pugay exhibited at Upfor Gallery in October. Selections from his body of work are on view at the Seattle Art Museum through Jan. 11, 2015. All images used with permission, courtesy the artist and Upfor Gallery, copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

The year between undergrad and graduate school, I think I got seriously complacent and depressed. I ended up playing a lot of video games and watching a lot of TV. When I entered school again, it felt as if I was not prepared because everyone seemed so serious and into what they were doing. I think feeling isolated like that really forced me to confront that complacency by addressing it through the work I started to make.

I was fascinated with using elements that harked to the redundant, the perverse, and the catastrophic—all of which can be attributed to the high-impact sensationalism that’s prevalent in video games and TV. I would just make lists of ideas and try to gun them out on surfaces one after another. I devoted myself to using list-making as a conduit for visual material.

TMN: How has your approach evolved over the years?

RP: Lately, I have been going off the lists, allowing more time for me to marinate in a work without knowing where it is going. Though I am still devoted to the process being about experience and allowing a multitude of everyday sources to converge on a surface. Having invested so much time to painting, I am also starting to look at other painters. Right now, I am really into J.F. Willumsen, who is super diverse in his approach but uses color and paint in such a confident way.

TMN: What do you mean by confident?

RP: For a painter who died in 1958, his work is really eclectic in subject matter. He’s confident in portraying his own weird vision of the world, I suppose, and allowing his intuition to guide his marks.

TMN: When have you been surprised by how people react to your paintings?

RP: I am always surprised by how people react to the work because I never, ever know how somebody is going to react. Whenever I display a new body of work, I definitely have my own favorites, but my favorites are rarely anybody else’s.

At Skowhegan, some sort of small wild animal got into one of the rooms and left a poop in front of one of my paintings. That was pretty surprising.

TMN: What was the first piece of art you ever sold?

RP: I think it was “Spy in Peril,” which I did in grad school. I sold it to one of my mentors. Totally sold it for an embarrassing price. Total amateur move.

TMN: You studied art in both undergraduate and graduate schools, and now teach. What’s been a challenging aspect of teaching your craft?

RP: I come into the classroom with the assumption that the students have ideas of their own artistic sensibilities and interests, and that they have no idea who I am or what I do artistically. So I focus my efforts in getting to know the students and their interests and providing them with parameters to work with. Sometimes, I try to provide parameters for projects that are completely experimental. There are times when it works, but then there are times when the project falls flat on its face. I think rolling with those punches has to be the most challenging part, but it’s also the most exciting part for me.