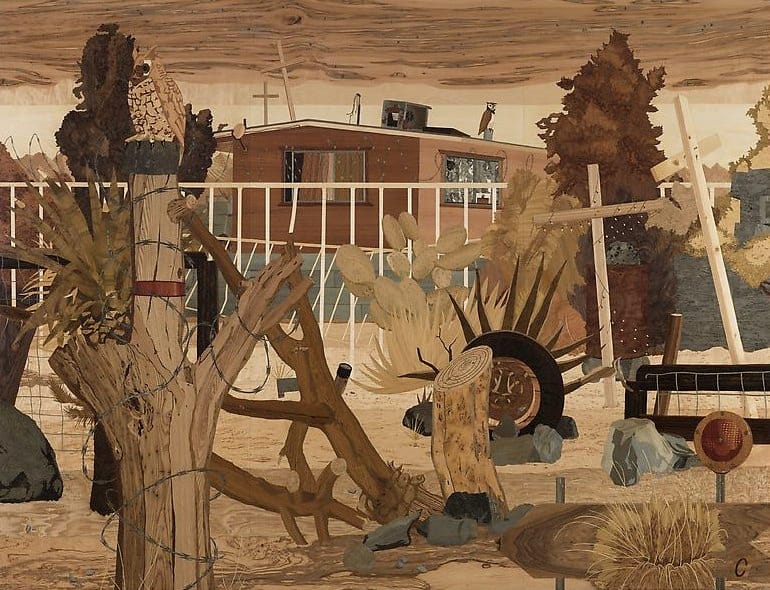

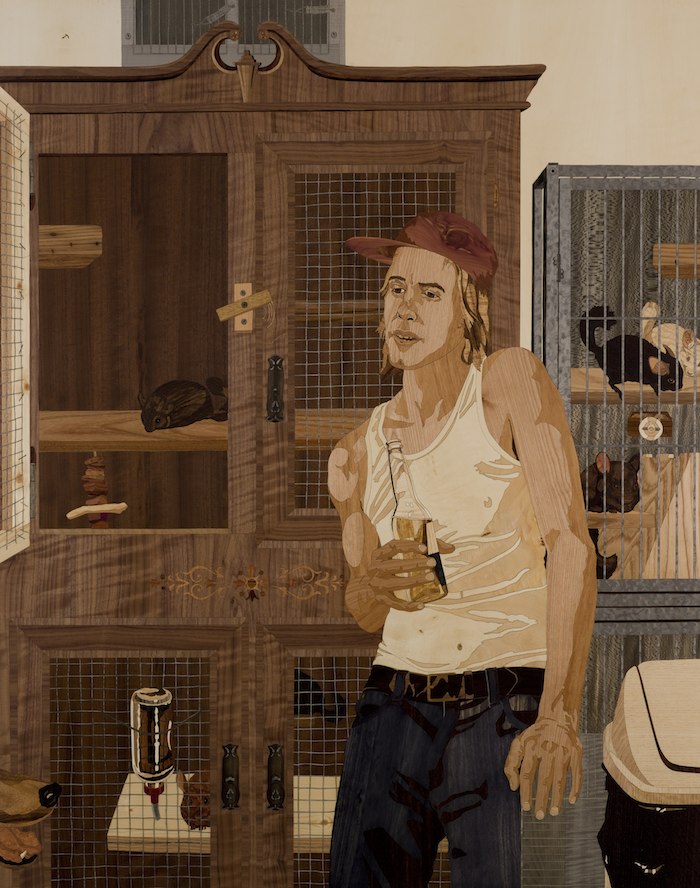

Foreclosed

Using a Renaissance practice of wood inlay known as marquetry, Alison Elizabeth Taylor reproduces scenes of foreclosure in Las Vegas.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

How did you start working in marquetry?

It was an evolving interest. First, I was using wood-grained contact paper in my paintings, then I started to make contact paper “inlays” using only the paper. When I moved to New York and saw the studio from the Ducal Palace in Gubbio at the Metropolitan Museum I decided to change my materials to real wood because the slight irony in the shelving paper needed to be replaced by something more substantial. The wood is much more expressive and new variety of veneers are constantly surfacing so I’m constantly learning. In addition to the formal attraction, I like taking on the history of this medium; its relegation as a craft or decorative art after a brief period of glory in the Renaissance is fascinating. Continue reading ↓

Taylor’s show “Foreclosed” is on view at James Cohan Gallery New York through June 19, 2010. Images courtesy James Cohan Gallery New York, copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

What makes the medium well-suited to the topic of foreclosure or abandoned homes?

The clarity and depth of wood is so beautiful that it can focus a viewer on something abject or unpleasant that they might normally ignore or look away from. Inlay also has a tradition of being used as trompe l’oeil. The medium’s history as adornment for the rich and powerful takes on special meaning when portraying the former homes of much less wealthy people caught up in the massive real estate crisis linked to trading by some of the country’s richest and most powerful people and institutions. Portraying damage that occurs in less than a second has a special resonance as I work on these pieces over weeks and weeks. I feel like I’m making a permanent impression of something that will be quickly covered up by a bank’s contractors.

What motivated you to choose the subject matter?

I saw a beautiful Victorian house in the Hudson Valley that had been completely restored by an owner through a laborious process: sanding, scraping, refinishing every detail of this very old, intricate building. The person was foreclosed on, and in retribution left the tap on the second floor running, flooding the house and destroying what they had worked so hard to save. As I continued to hear about the foreclosure crisis I couldn’t get the images of falling plaster and water-stained walls out of my head.

How did you find, approach, and study the properties?

At first, I tried to go through realtors, but this was very difficult in the beginning. They were either suspicious or dismissive as soon as I mentioned I am an artist. I began going around with a guy who gets into foreclosed properties that are shut to the public and takes photographs for investors. At one point we got a lockbox code, but most of those properties had already been cleaned up by the time we got to them. This was in the beginning, when banks were keeping up with it. Eventually the crisis got so bad that I could just contact realtors and find lists of properties. Some I just slipped in through the back door, some through a broken front window.

Do you know individual stories of these homes?

Many of the homes I visited during my research for the project were in Vegas, where I grew up. Each house has a story behind it of what happened there, and I have no way of being sure what is what, but I’ve learned to read the damage. Often times there are layers of vandalism as owners are followed by squatters or kids doing random destruction. Copper theft leaves very distinct holes and they are pretty consistent. Anger and frustration take all sorts of forms, but sometimes you can read the direction or implement (pickaxe, foot, knife, etc.) that was used to make the hole.

What effect does abandonment have on the surrounding communities and our sense of space?

The abandoned houses are bad for the people left behind as well as the people forced out of them. There were streets in outer Las Vegas in brand-new developments where four out of five houses were empty on a street. Imagine being that last family living on an empty street where all of your neighbors have lost their homes. It destroys any sense of surrounding community and is a constant reminder of how tenuous jobs, homes and quality of life can be. For the people forced out, obviously it is much worse. During my research process I found many houses where people had been fixing up old places or had kids and were obviously trying to make a go of it, but had been forced to leave in the middle of the night, leaving the kids’ clothes and toys scattered everywhere. I really don’t know how to reconcile the “dream of home ownership” touted throughout this country as an achievable and necessary part of life with the byzantine financial system that was allowed to create these empty houses and homeless people. It is just baffling.