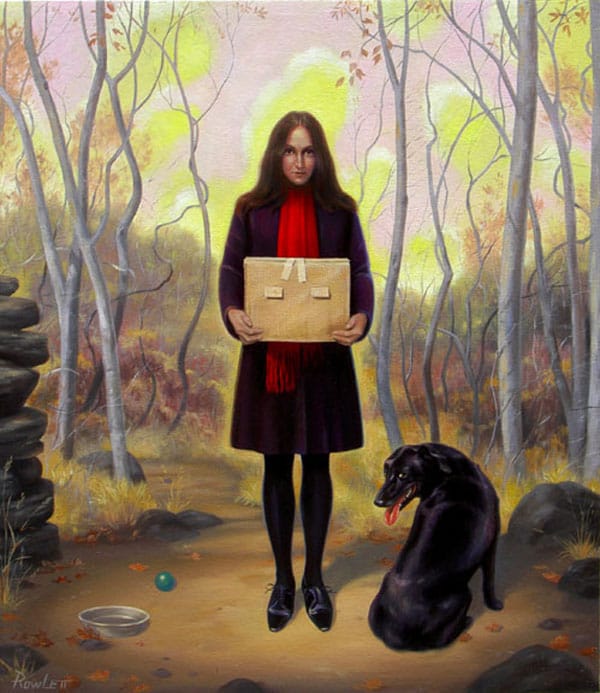

Friends and Family

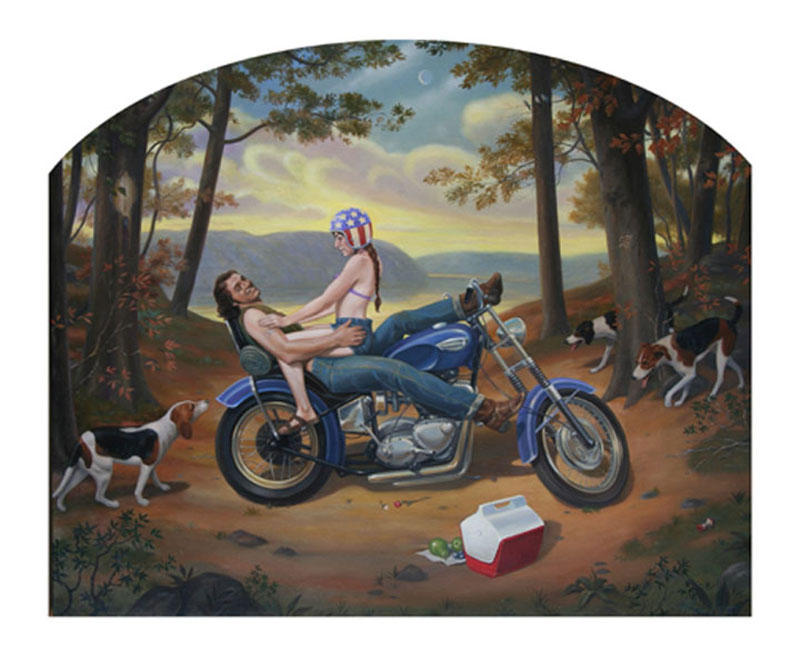

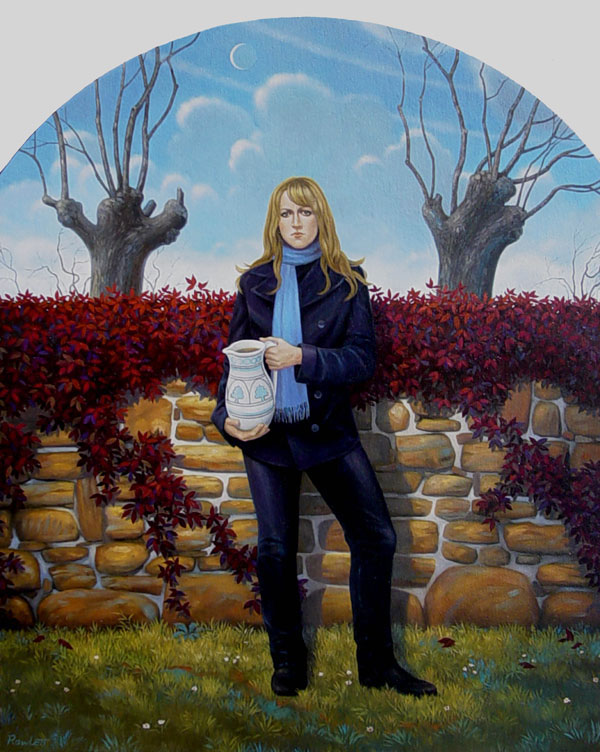

Terry Rowlett searches for meaning through contemporary work with undeniable ties to painting’s history. In his work, Rowlett’s friends mirror his own struggles and exalt his triumphs.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

Who are these figures in your paintings?

All of the people are friends of mine, or people that I know. Five of the paintings were done when I was teaching last fall in Italy, and they actually had students in them. I consider them my friends, but the relationships didn’t have a lot of depth other than that one semester. Continue reading ↓

Terry Rowlett’s work is on exhibit at Jenkins Johnson Gallery in New York City through July 20th. All images courtesy Jenkins Johnson Gallery. All images copyright © Terry Rowlett, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

Which paintings were done in Italy?

“The Encounter,” “The Night Watch,” “The Blue Boy,” and “Catching the Moon.”

Do you have an idea, going in, of what you want the scene to look like or what you’re trying to convey?

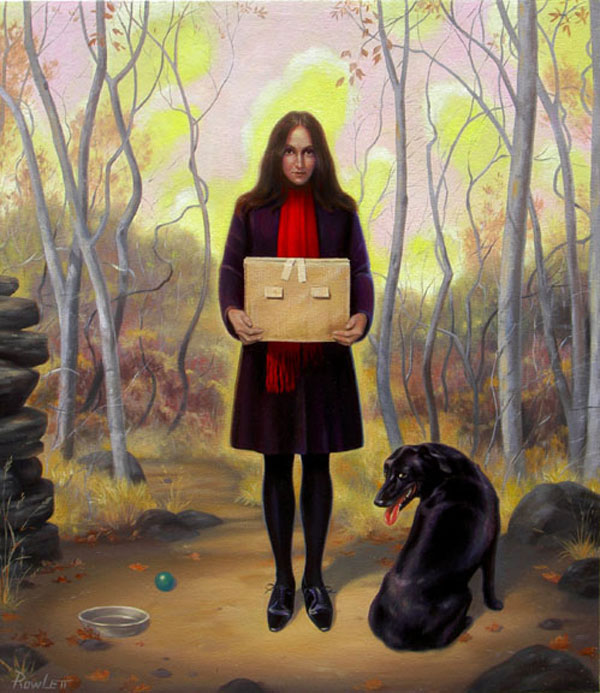

The rest are friends I know quite well. I come up with an image or idea, and then I sort through all my friends and decide who best epitomizes what I’m trying to get across in terms of body type. I shoot a couple of rolls of pictures of them in different poses, and I’ll work out my idea. I sort through the photos and see one that captures this better than the other photos, and then I start to work with that.

What kind of concepts do you have in mind at the beginning of the process? Objects, scenarios, a character type?

More than a character type, a character type involved in some sort of worldly search. In Italy, most of the people in those paintings were involved in the act of pleasure, enjoying life, and being alive. There are other people in some of the paintings, brooding people, searchers, who are doing other things; questioning God or something. In that case I’d pick a personality type that deals well with those kinds of issues.

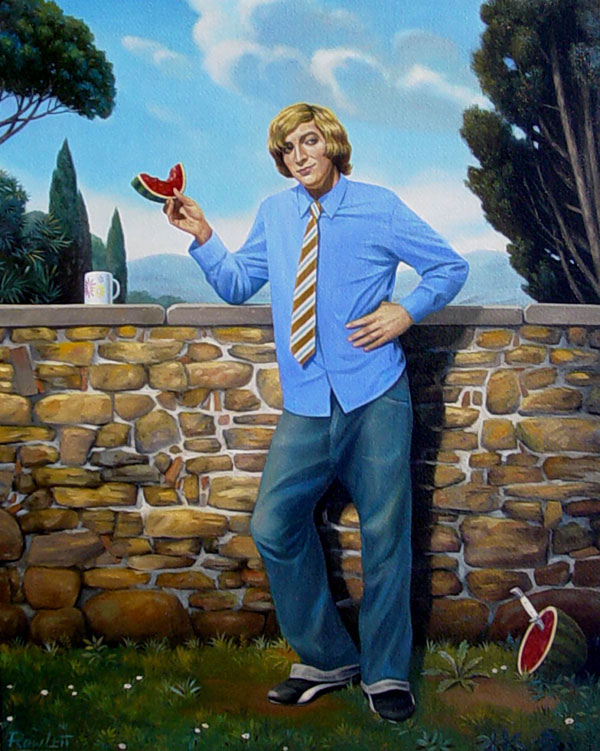

How come the paintings you made in Italy reflect such pleasure and happiness?

I was really depressed for the last three or four years. I’d been consumed by the war in Iraq and with George Bush and his policies. Certain people are really affected by it and I was. So, when I went to Italy for four or five months, I purposely tried to forget the woe and the idiocy of what we were involved in, the tragedy of the war. I went there and it was easy to find people being happy and having good values and having a good life. I immediately started to relax and I started to breathe in life again. I started finding topics of pleasure and beauty. The other half are more about the costs of the war in Iraq: There’s more stress or struggle in those paintings than in the other five, which are about people living in a peaceful, happy, just world. That’s what’s been on my mind since I got back in February.

So, in general, the work reflects your feelings at a particular moment?

Definitely 100 percent how I feel at the time, what I’m aware of at the time. Almost every painting deals with my epiphanies, realizations, and struggles.

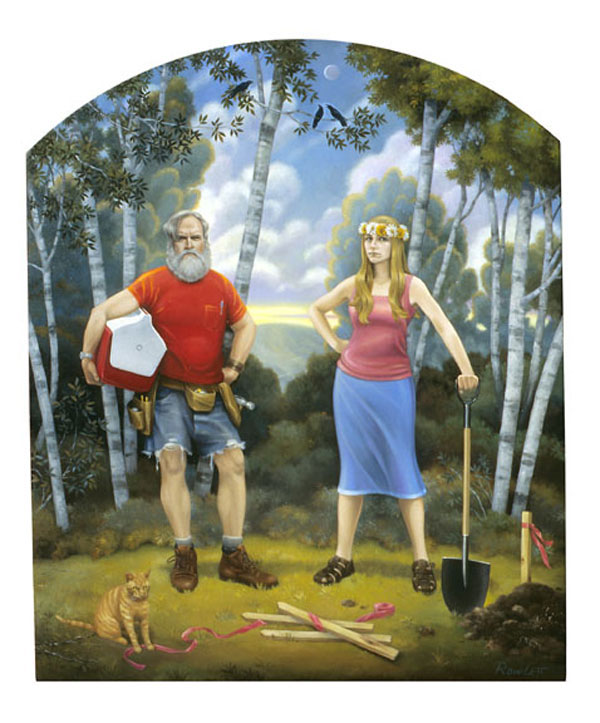

It’s interesting that the style of these deeply personal paintings references Renaissance painting so heavily.

I’m very historically anchored in my painting style. It speaks to me personally, but I purposely chose to have a timeless quality to my paintings. I didn’t want to get caught up in current, en vogue styles of art because it easily gets limited to a 10-, 15,- or 20-year period. I don’t want to limit my work because of style. From 1500 or 1600 until modernism there was a 400-year period where people used realistic, figurative painting to comment on life and philosophy or religion. And it seems to [have been] very successful.

It’s interesting to hear you talk about wanting to ground your work in the past since the figures look wholly contemporary. They’re relatable and culturally recognizable.

I do want to paint for us and for future generations who might see my paintings 200 years from now. I hope that they will just lock into the realistic paintings of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries.

You were raised a devout Christian. Aside from providing subject matter, how has your religious upbringing affected your life as an artist?

Having been a person of faith [gave me] faith in my calling. [I started thinking] I had a certain blessing or duty to God or my faith. I think it gave me more strength than other people in a certain way. Ironically, it helped me through my first seven or eight years of struggling as a painter. About 10 years ago, I lost my faith. Since I already believed in my art, after I lost that one true motivational force, I was going with enough speed that I was able to switch my focus more towards a non-religious subject matter, toward humanity and nature. A person can look at my paintings from the beginning and you can probably see the transformation of being a crazy true believer, to starting to leave that, to being just an observer of life, to where I am now, which is commenting on looking for beauty and joy, and on other topics of mortality.