Get Closer

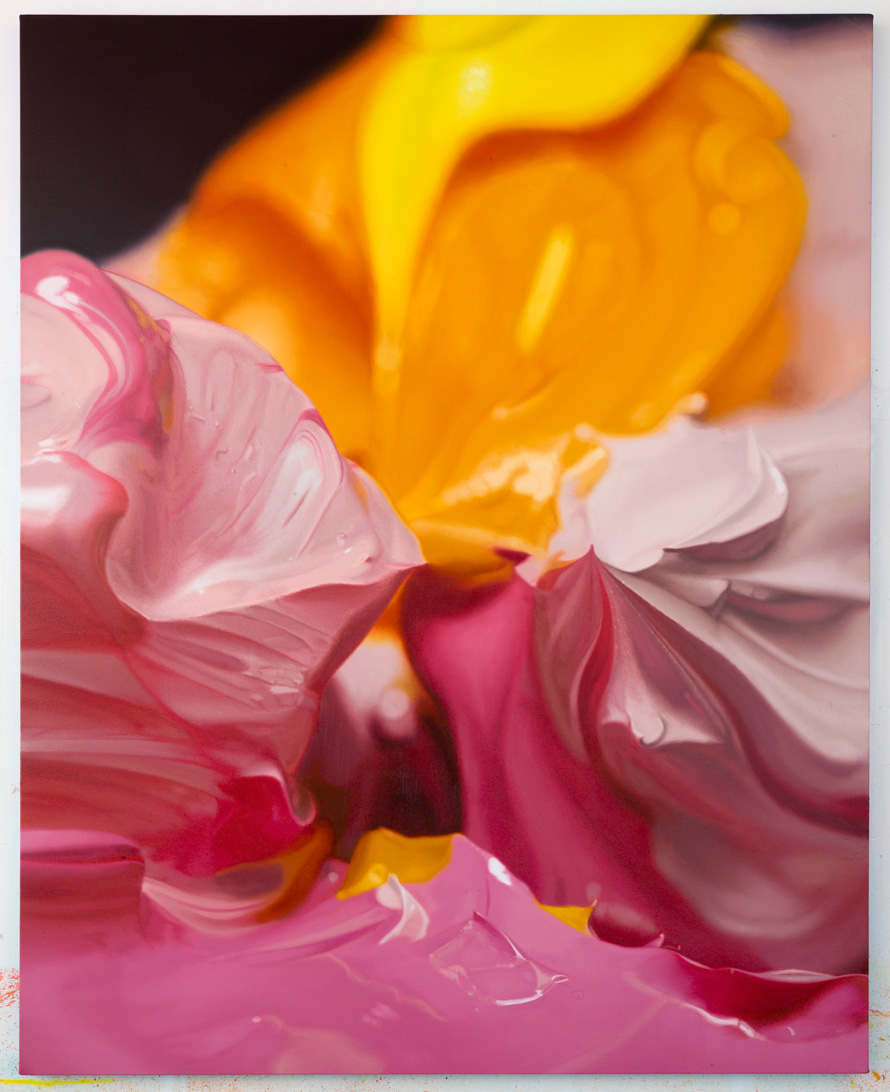

Ben Weiner’s paint-splattered palette isn’t just a tool, it’s the basis of his work: landscapes that magnify globs of oil paint a thousandfold and videos that turn the process of mixing paint into a slow ballet.

Interview by Nozlee Samadzadeh

TMN: Describe how you create these paintings.

Ben Weiner: My process derives from my interest in medium specificity, a practice in which art analyzes the means of its own creation. I base each painting on microscopic photographs I take of my palette while I paint. This creates a cycle or loop, in which the making of each painting generates the source imagery for the next painting.

In order to paint such detailed images, I mix palettes of hundred of little blobs of paint in different colors and tones, using my photographs as source images. I apply these colors with soft brushes and blend them together to create shifting sharp and soft focus optical effects. Continue reading ↓

SMUSH is on view at Benrimon Contemporary in New York City through Dec. 15, 2012. All images used with permission, copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

While I am doing all of this, I have my camera (the lens has a microscope attachment) next to my palette, and periodically take microscopic photographs to document interesting formations of paint blobs and the traces of mixing and blending the paint. Based on that crop of photographs, I create a composition for the next painting.

In developing this process, I was inspired by the omnipresence of social media and digital photography in our lives. As we experience things in the physical world, we are simultaneously photographing them with our phones, tweeting about them, etc., and when we look at those photographs or friends react to our tweets, it shapes that experience. Similarly, by photographing my palette I document my experience of making each painting, and that provides the jumping off point for the next one. That act of documentation shapes the course of the body of work.

TMN: Why did you gravitate towards extreme detail in this style?

Ben Weiner: My magnified imagery reflects my interest in science and its influence on our contemporary perspective. I am interested in the way a microscopic view allows a person an intimate knowledge of the workings of a subject, while simultaneously alienating them from their normal experience of that subject.

When I was growing up, my father, a doctor, used to have his medical journals lying around the house. Looking at these journals, I was fascinated by microscopic photographs of the interior of the body and its organs. They presented a disorienting experience, in which I was seeing the body from an immersive, microscopic perspective that subverted my ordinary experience of measuring all things in relation to myself—to my body.

Similarly, the blobs of paint in my paintings appear alien and otherworldly, even though they depict the stuff from which they’re made. This experience of transporting the viewer has always been part of what painting does, and I enjoy creating a tension similar to what I felt when looking at those medical journals—the viewer knows they’re seeing paint, but the microscopic perspective removes it from a mundane, human-scaled experience.

TMN: What have you learned about your medium in creating these artworks?

Ben Weiner: My work centers around oil paint, a medium I studied in school. Oil paint obviously has a long history and a rich tradition.

As there is so much knowledge compressed into traditional oil painting, I enjoy using current technology to expand on different aspects of this medium, such as the chemistry of paint. Whereas paint chemistry has traditionally been applied toward creating brighter, more archival painted images on canvas, I gave it its own spotlight in my sculptures and video works. In doing so, I learned a lot about it.

In this show, for the first time ever, I created sculptures in which I grew crystals of the minerals in oil paint pigment, specifically carminic acid and potassium aluminum sulfate, used to make carmine pigment. I grew these carmine alum pigment crystals in my studio by dissolving the chemicals into solutions in large vats, and then letting them evaporate and crystallize.

In order to figure out my approach to making these sculptures, I spent a lot of time reading about the minerals in paint pigment, and methods of paint production, as well as conducting different experiments to figure out what would produce the best looking crystals. As with painting, the finished works represent an interaction between the natural tendencies of this material, and my reactions to that.

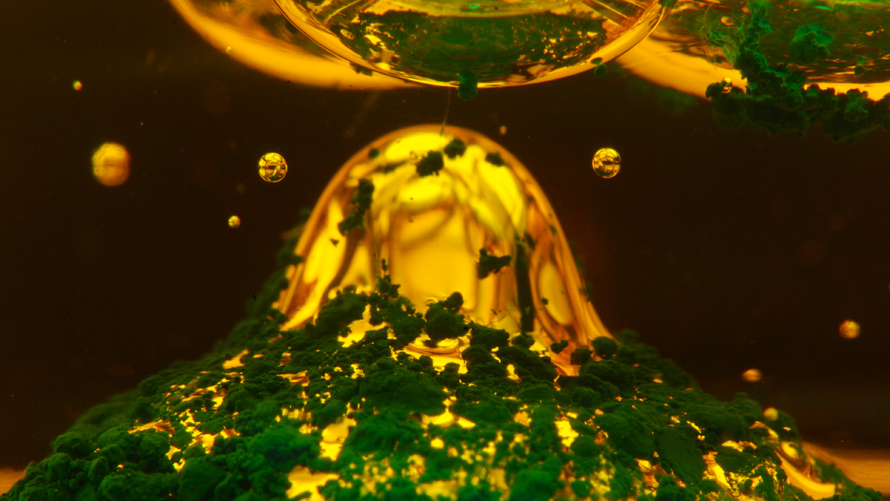

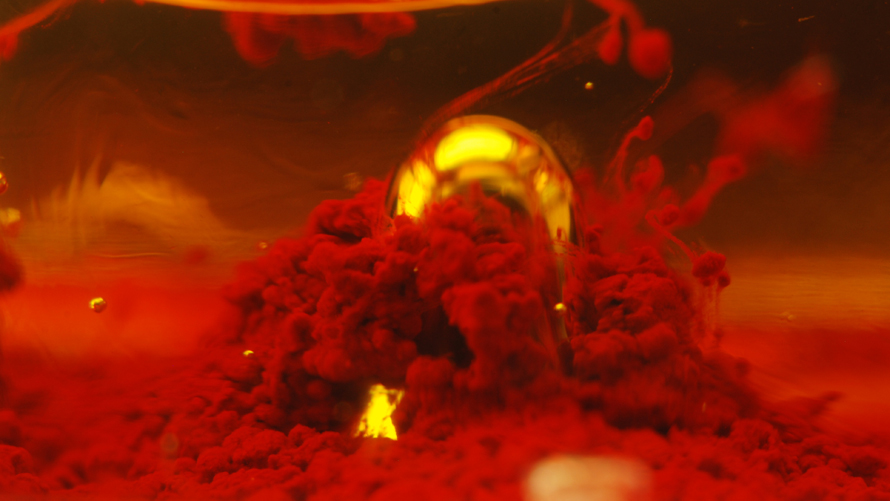

For my videos, which depict the traditional process of making paint by mixing together pigment, oil, and varnish, I researched different types of oils and varnishes used in painting. The videos magnify and speed up these materials as they dissolve into one another, and in order to produce visually engaging reactions between the different materials, I experimented with different oils and varnishes. I ended up using Venice Turpentine, a viscous mineral spirit favored by many old masters, which released giant, beautiful golden bubbles as it mixed with the pigment.

Together, the paintings, videos, and sculptures in this show present a narrative that shows how natural materials are refined into paint, and paint is refined into a painted image: the sculptures show how pigment crystals are grown, the videos show how pigment and oil are combined to make paint, and the paintings show how these paints are mixed to create a painted image. So there is an almost didactic quality to the show itself.

TMN: Do you consider these paintings to be landscapes?

Ben Weiner: By creating paintings and videos in a horizontal, landscape format I engage with many themes connected to landscape painting and the environment.

I am very interested in the connection between nature and culture—our natural history of having evolving from our environment, the way we transform raw materials from the environment into human-made surroundings. By magnifying paint, a mass-produced material, I reconnect with its natural origins; the natural materials from which it’s made— granules of pigment, oil-slick surface surface, etc. Relating to my medium-specific interests, I am exploring how art is a process of refining natural materials into cultural objects.

My sculptures take this further by channeling the natural tendencies of mass-produced art materials—allowing pigment to crystallize and grow. This is a microcosm of the natural physical processes we channel whenever we build or create anything. In less developed societies, these processes are more apparent: chopping trees down to make houses, building fires. But in our technological society, it’s still present, but you need to literally look closer to see it. So, where traditional landscape painting observed the natural environment, I observe microcosms of the natural environment within the human-made, technological society we’ve cultivated.

TMN: What are you working on now?

Ben Weiner: I am beginning to work on a show for Mark Moore Gallery in Los Angeles a year from now. I’m developing further what I’ve been learning about crystal growing, as well as learning ways to observe paint at a higher magnification, so I can observe the working of more processes, such as what happens when paint dries.