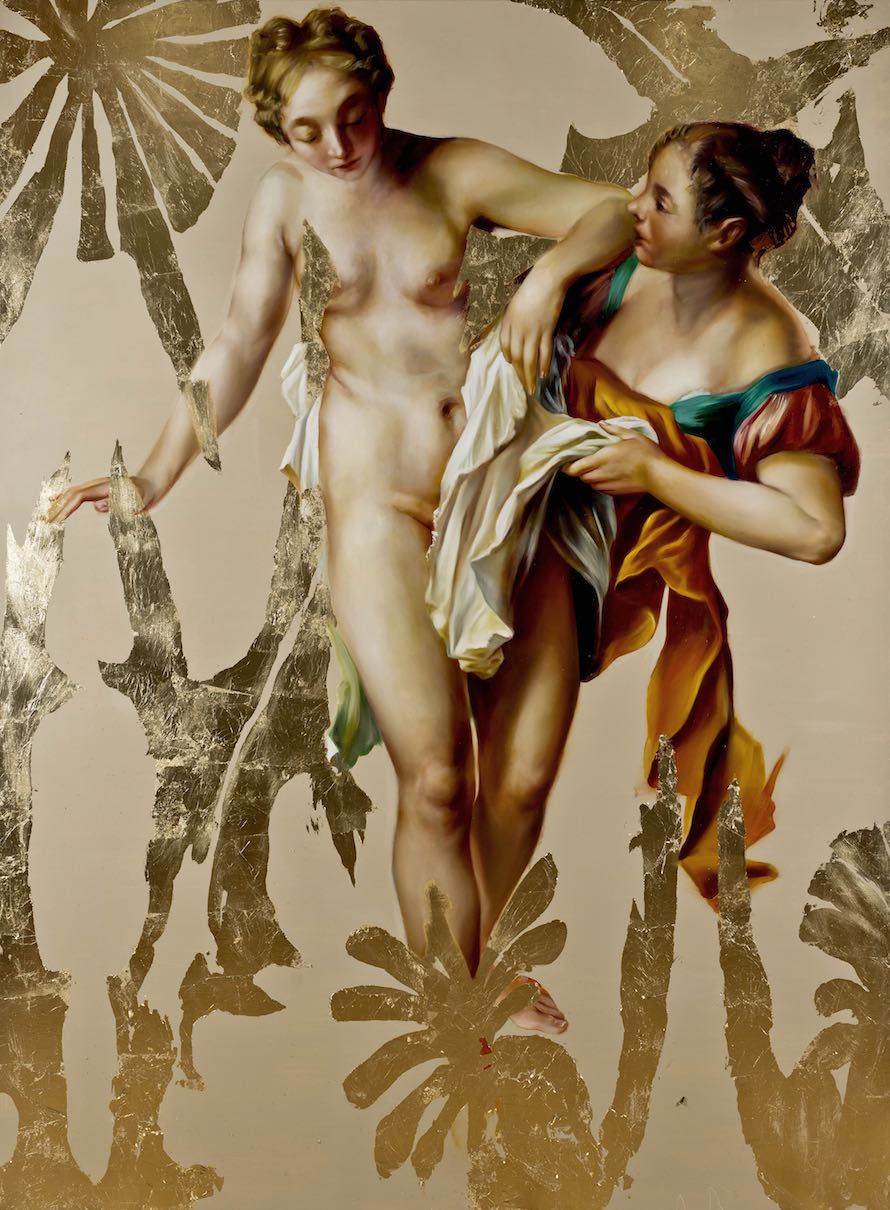

Ghosts in the Sunlight

Female subjects painted in classics by old masters—“Diana After the Hunt,” “The Rape of Europa”—get their voices restored, and with them new narratives and powers.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

The Morning News: The women in this series, where did you find them?

Angela Fraleigh: The body of work borrows figures from a variety of painted mythological interpretations by old masters—Diana After the Hunt, The Rape of Europa, and The Allegory of Fertility, among others.

The fraught sensuality of these stories has been compounded, over the years, by their representation. The women in my work are originally from paintings by Baroque and Rococo masters such as Jacob Jordaens, Francois Boucher, Francois Lemoyne. In their work the stories were sifted through the lens of the painter and through the eyes of an era. These were artists whose great themes were pleasure, beauty, and abundance; hints of refusal, fear, or coercion would only spoil the party.

The echoes of these idealized forms still reverberate and lap at the shores of our consciousness, forming the ways we come to understand ourselves and make meaning in the world.

By pulling at the shadows of old-master paintings my work asks the question of what dormant new narratives might be found in the female subjects that inhabit them. What invisible histories lay in wait, or what complexities of power might be unearthed? Is it possible to restore autonomy to these models, to whatever nuances of expression might’ve been contained in their poses? Maybe it can’t be “restored”—they’re long gone—but perhaps something new might be revealed. Continue reading ↓

Angela Fraleigh’s Ghosts in the Sunlight is on view at Inman Gallery through Jan. 3, 2015. All images used with permission, copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

TMN: So how did the work begin to take shape?

AF: While on sabbatical this past year I began looking at origin stories and thinking about myth. I was reading through Joseph Campbell’s theory of the “monomyth” when I realized there were few female protagonists that fit that particular narrative structure of the hero’s journey. I wondered if there would be a difference—could there be splintered versions of the hero’s journey to encompass the nuances of the female experience?

Then I found Marina Warner and have been greedily consuming everything she’s ever written. Her book From the Beast to the Blonde, in particular, has been fodder for the way I’ve been thinking though this latest body of work. In it she talks about how women’s voices have been silenced throughout the ages. She displayed several propaganda style prints from the Middle Ages to the present warning against the dangers of women gathering and gossiping. Women knew things—they knew how to have abortions, they knew about sexual pleasures; they had medicinal tinctures and so on.

In many ways the Hero’s journey for the female character resides in fairytale. Not the sanitized Disney version, but the erotic and violent wonder tales told the world over by “old biddies,” grandmothers and nurses. These are stories that had been passed down by generations of society’s voiceless women. These stories taken out of context and devoid of their bite read as entertainment, but in their day they were the whispers of progress: At times cautionary tales, in other instances emotional dramas meant to inspire rights and privileges outside normal social codes of the day, all moving toward broader terms of freedom for the narrator and her coterie.

TMN: Did these appeal to you on a painting level?

AF: I liked thinking about these gatherings, whether it be the birthing bed, the bakery, or in the salons of the aristocrats, as subversive meeting places where women could network. And that sharing stories alone might be so powerful as to instigate change.

Many of the paintings that I chose to re-envision are taken from the Rococo era, an era often swept under the rug of art history for its femininity and frivolity. This was a time when women were key players in the creation of culture. Women like Madame Pompadour were the primary patrons of many of the artists associated with that time such as Boucher and Fragonard. Much like the stories being told of that time and their role in creating more opportunities of freedom for women, this body of work questions those complexities of power. How we might use what we have to get what we want.

TMN: So much focus here is on the body—sensuality, complexity, gradation. What compels you most to paint these days?

AF: What is the famous de Kooning line? Flesh is the reason oil paint was invented? For me flesh is the perfect subject to perform all the things I love most about painting. Oil paint is so versatile—it can be pushed to so many extremes. Juicy slabs, silky wisps, transparent floods of color. There is topography to painting, one you have to be fully present to see and understand. You can’t really get it from reproduction, and in this digital age I take great solace in that. The paintings I love the most are generous in this way. They have a scaffolding, a built effect that beckons an optical engagement, asking one to read not only the surface, what it is and what it means, but also to read the internal structure, eyeing from the tippy-top membrane down deep into the weave of the canvas.

TMN: When did the addition of the metal leaf occur to you? Was the idea more inspired or calculated?

AF: The use of gold leaf is new in my work but in my mind functions similarly to the pours of glossy oil paint you might see in some of the other works, both formally and conceptually.

The process of painting most of my images alternates between control and chance. I’ll lay out the figurative composition in a traditional upright manner, but then lay the canvas flat and pour cupfuls of oil paint and synthetic resin. This creates more of a collaborative process, as it inevitably invites indiscriminate painterly moments that I don’t intentionally create or control.

Conceptually this process allows the paint to function as a protagonist in the narrative. The physicality of the paint both cankers and covers the story, obscuring individuals and becoming a carrier of meaning. Through the examination of power dynamics of social constructs, like gender and class, the paintings often expose the fissures that occur when the ideals from one point in history are translated into another.

TMN: But on a technical level, before meaning’s introduced, how does it work?

AF: For a while I had been wanting to incorporate a visual effect that would read as more embedded in the paint, something seductive that would also read as decay, less visceral yet opaque.

I began tie-dying the canvas before painting on it to see if that would yield anything. I also started painting on printed textile and recreating tapestries as a ground for the figural elements. Nothing really came together, but all of that eventually led me to textile design as an abstract element—and thinking about the first female textile designers.

One that popped up in my preliminary searches was Candace Wheeler. She was one of the first women to be paid for her work with Tiffany. She created an all-woman design firm, Associated Artists, and fought hard for the economic freedom for women in the early 1900s. The gold-leaf abstractions in all of the new paintings are a pattern taken from one of her designs.

Anyway, I was playing with painting in the textile design but it wasn’t giving me the same charge, so I tried the gold leaf and found it served my needs on several levels. It’s alluring—you want to look at it, but when light hits it, it pushes back out at you. It was a physical way to mimic the experience of thinking you see one thing, but in fact see another.

TMN: You put a lot of care and lyricism into your titles.

AF: I like how a title can sit beside an image, not illustrating it or describing it, but holding its own, creating something new—something entirely different, that perhaps the painting alone doesn’t do. Titles can puncture or punctuate; they can undermine assumptions or complicate the image. They might make the reading feel broader or point to something nuanced without being overbearing. I’m really interested in that moment between the text and the image, that area between that reads as a sigh, a shudder, or a pause.

The titles I choose are often fragments from larger texts—half a line from a poem or a scrap of dialogue. These found snippets echo the fragmentary nature of the images themselves. I collect these strings of words, and when a painting is finished I hold them up one by one, hoping to find a match, a combination that yields something greater than the sum of its parts.

TMN: We like to ask all our artists: What was the first piece of art you ever sold?

AF: Gosh, I think it was a painting right out of undergrad at the Stissing Mountain house in Rhinebeck, NY, near where I grew up. I had a show in the upstairs empty space of an old hotel. I don’t remember how that came together but it was exhilarating at the time. I thought “Wow, this is what it’s like to be a real artist!” I was naïve obviously, in so many ways. But I still get that charge when I have an exhibition, or something “works” in the studio, or when I read something powerful that I know will factor into my next project.