Going Dutch

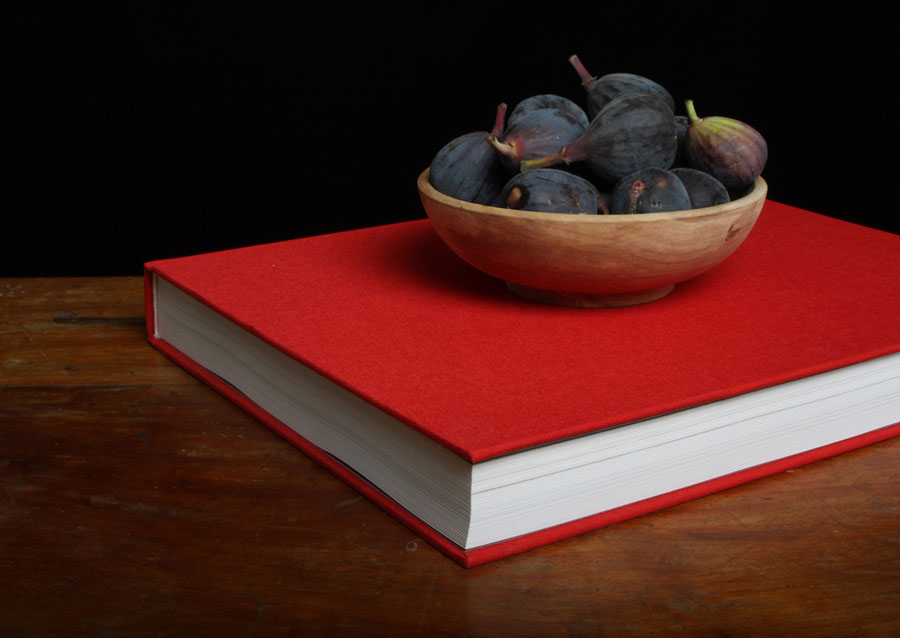

Taking inspiration from Dutch vanitas paintings, photographer Justine Reyes creates still lifes from contemporary objects, getting the composition, textures, and colors so precisely “right,” it’s a wonder we’re not seeing some 17th-century Flemish take on contemporary life.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

How did Vanitas begin? How long has vanitas painting held an allure for you?

I was first introduced to vanitas as a genre and concept in grad school at the San Francisco Art Institute. I took a course called “The Sacred and Profane” with Linda Connor. She did a brilliant lecture on vanitas that inspired me and has always stayed with me but it wasn’t until I applied to the A-I-R program at the Center for Photography at Woodstock that I developed the idea for this project. I began shooting these images when I started my residency at C.P.W. and had a tremendous amount of support from the staff and a month away to focus on nothing but my work. Continue reading ↓

“Vanitas” is currently showing at the Center for Photography at Woodstock through Feb. 28, 2010.

Interview continued

At least to me, Vanitas still lifes look like memorials—final arrangements, the skulls, the detritus. Are these portraits personal expressions?

These still lifes are like memorials in a way. All of the objects are things that I’ve owned for a very long time and things that had belonged to my grandmother. Pairing objects that belonged to my grandmother with my own possessions speaks to the concept of memory, familial legacy, and the passage of time. Both the decomposition of the natural (rotting fruit and wilting flowers) and the breakdown of the man-made objects reference the physical body, life’s impermanence, and the inevitability of death. My work examines identity, mortality, and the longing to hold on to things that are ephemeral and transitory in nature.

Can you describe how you’d go about setting up one of these shots?

I work very intuitively, so setting up one of the still lifes is like putting a puzzle together; I have all the pieces laid out in front of me but I have to figure out where they go. It is a very slow and meditative way of working. I’m using a four-by-five camera and studio lighting so that also helps slow down the process a little.

What do these pictures mean to you when you see them in the gallery with an audience?

This work is currently on view for the first time at the Center for Photography at Woodstock so it’s hard to explain what the experience of seeing the reaction of the audience is like. Having any work on view to the public is both nerve wracking and very freeing. Once they’re out there they take on a life of their own. I imagine it’s like sending your child off to college. You hope that you’ve prepared them to exist in the world on their own but at some point you just have to let go.

What are you working on next?

I am working on a new piece called “These Last Things,” which consists of large-scale color photographs of the interior of four drawers. I took these drawers out of my uncle’s dresser after he passed away. The title refers to the Four Last Things from the Novissima: Death, Judgement, Heaven, and Hell. I chose this title not only because my uncle was Catholic and very religious, but also because it refers to the things we leave behind when we die. These drawers are the last physical trace or vestige of my uncle left untouched in his memory.