Hospice Behind Bars

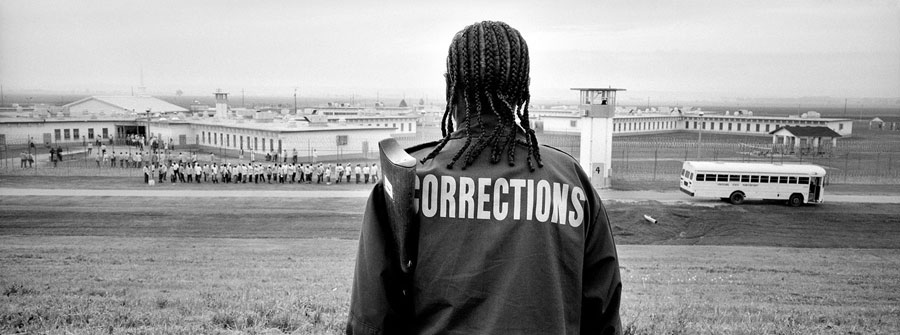

At a Louisiana prison best known for controversial rodeos and keeping the Angola 3 in solitary confinement for more than 29 years, there’s a glimmer of hope and humanity: a hospice where inmate volunteers provide end-of-life care for dying prisoners.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

How did the project come about?

It started as an assignment from a small magazine called Imagine Louisiana that’s since folded. I shot it from all kinds of different angles because I knew this might be my only chance to have access to this program. After that was done, I asked to come back. I showed them a little bit of the work that I’d done with my film camera, told them about the work I wanted to do, and [the hospice] granted me permission. It was sensitive; each visit was a new request. Continue reading ↓

Lori Waselchuk’s photos from the hospice at Angola prison are now part of the traveling exhibit “Grace Before Dying,” scheduled to show in most Louisiana correctional facilities this year. She spoke recently at the Apple Store SoHo Theater. All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

How many times did you go and shoot there?

I went over a three-year period, less than 10 visits. I knew what I was looking for and I wasn’t sure if it was going to be possible. I was extremely patient. The prison was very pleased with the magazine work. I have to give them a lot of credit; it’s hard for security-minded people to grasp what creative-minded people are trying to do. They kind of took a chance. They had to organize security each time I came in. I certainly put a burden on their structure.

What’s the history of the hospice program in Angola?

It began in 1998. The warden learned about hospice in prison and he started making inquiries and brought in people and actually initiated the process to bring hospice. It is a nationally certified program. I think there are very few prison hospices in the United States. All the caregivers are certified, they go through two-week training, and the volunteers apply to the director, who’s actually a staff nurse. The prison never hired an additional employee. They used the resources they already had. The prison doesn’t use any funding. The program itself is self-funded through both donations and through their quilting program.

When I first heard about your project, I was interested that it was happening at Angola—my sense of that prison is that it’s a really bad place.

Its history is that it was one of the most violent prisons in the country. Certainly one of the most dangerous places to be incarcerated. In the ’70s, the murder rate was hectic there. But things have changed since then. There’s a mainstream population there that lives in dormitories and has access to self-help programs and libraries, so through many different kinds of programs there’s been a cultural shift and now it’s one of the safest prisons in the country. This still doesn’t make it a nice place. It’s still a maximum-security prison.

Has the hospice been a part of this cultural shift at Angola?

It’s safer for the inmates and I think the hospice program has contributed to lessen that feeling of hopelessness that lifers feel. Before hospice inmates would die alone, be buried in cardboard boxes in numbered graves. They were afraid to go to the hospital because they felt they’d be unattended. They’d rather be unmedicated and untreated in the main population where they were close to friends than go to the hospital where they’d be forgotten and left alone to die. The hospice has contributed to an attitude shift where, if you cooperate with the security system and the way things are, you have access to programs where you can improve your education, your artistic skills, participate in the public events, and it’s worth it for these men to maintain their own sense of security where they live to keep these programs.

But Louisiana sentencing laws are off the charts in their severity. Though Angola has become a place where the inmates are safe generally and can serve their terms, I would ask that people look at the sentencing situation.

Once you were in the hospice space did you have pretty open access?

Yes, that was facilitated through the hospice coordinator and she really believed in the project and put in the extra time for me to be there.

What did you see and learn when you photographed in the hospice?

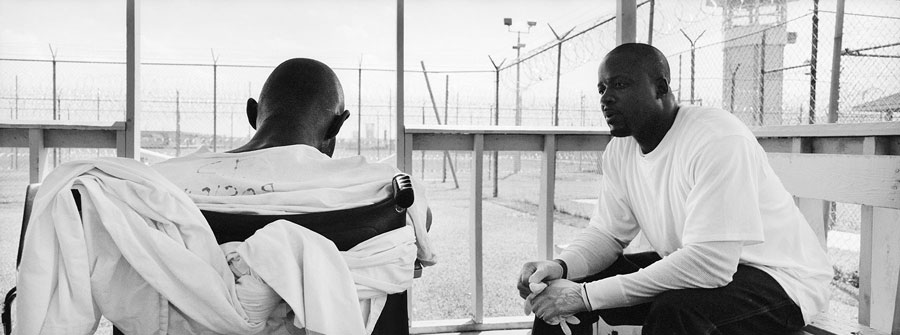

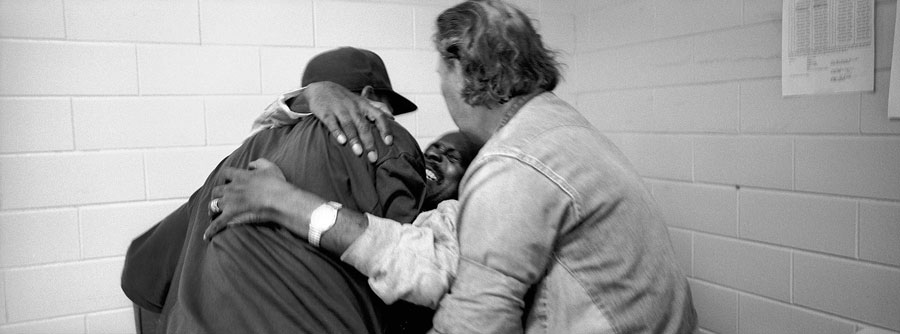

My eyes were opened in terms of what the prison system required, and the day-to-day reality of serving a life sentence. I had glimpses of what that might be like. It’s one thing to observe it and one thing to experience it. I just observed different things about what a person who finds themselves serving a life sentence experiences. I’m always looking for examples of humanity. I’m not surprised by finding it in prison, or in finding it in people convicted of murder. For me, the crime doesn’t define the person but it does define their life, path, and reality. And it does define realities of the victims. But it doesn’t define what the inmates are capable of on the other side: compassion, humanity, love.

So you saw this as a transformation that happened through working at the hospice?

I saw that hospice taught them things they were surprised to learn and do themselves. The philosophy of hospice, looking after somebody in their final days, making sure they are as comfortable as possible, listening to what patients might need and responding to it—and responding to the physical needs—that’s the hard work. The cleaning, the washing, the long nights, the hand-holding, and also [the volunteers] became facilitators with friends and family. They learned things about how to help family members say goodbye. They help people find the words and find the place to be in the context of death. They not only discover this in themselves, they were able to share it with others—the free population that were granted access to their family members, the inmate population, as well as the security and medical staff. The security and staff didn’t trust this at all, they thought it was a scam; they thought these guys were going to abuse the system. It was all suspicion. But over the 10 or 12 years that they’ve been doing this now, they’ve really convinced a lot of people and also taught a lot of staff members about compassion and that crime does not define the person. I was really inspired by these men; I wanted to make pictures that rose to how much I felt they could share.