I Am My Family

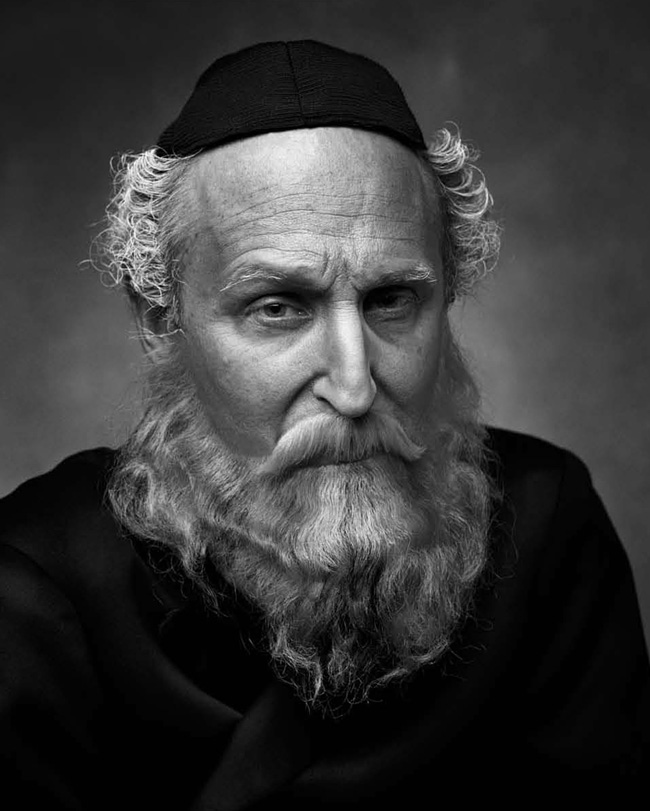

Say your family isn’t very good about keeping photo albums—why not create your own? Rafael Goldchain transforms himself into his ancestors to understand them better.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

As the press materials for Rafael Goldchain’s new book, I Am My Family, state:

Photographer Rafael Goldchain’s Polish-Jewish ancestors emigrated to South America in the 1930s, and many others perished in Poland during the Nazi regime. Also lost in the turmoil of war and emigration were most of the portraits of his extended family. When Goldchain became a parent himself, he decided to make up for this lack of evidence and recreate the lost gene-rations of the past, in the present.

See our talk below for Goldchain’s thoughts about portraiture and family, or stop by the Galerie Claude Samuel in Paris where his work is currently on show (he will be there on Oct. 19, 2008). Read the interview ↓

All images copyright © the artist, courtesy Princeton Architectural Press, all rights reserved.

Artist interview

Where did the book begin?

The idea of the work in the book originated from work I was doing while I was a Master of Fine Arts student at York University in Toronto. I had been doing portraiture and documentary photography for some time and came to the realization that my photographs were mainly about my relationship to my subjects and my particular status as an exile.

I chose to photograph myself as a means to be directly autobiographical. I started creating characters drawn from my memory of various stages of my life. One of those characters was based on my maternal grandfather. The photograph I made of myself as him had emotional intensity and conceptual challenge, and it determined the direction of my work since then. Parallel to this I had begun documenting my life as well as researching the lives of my ancestors. This process contributed momentum and material for the images I made.

How did you prepare for each photo?

Sometimes I prepared extensively by researching biographical information drawn from family members, my own memory, family album pictures, etc. At other times I drew inspiration from period photographs from Pre-WWII Jewish life in Eastern Europe published in various books.

Part of my preparation was also research of genealogical information in order to establish precise family connections, or to find our where my ancestors came from, amongst other kinds of information. Preparation also included finding suitable clothes and other props such as hair pieces, jewelry, gloves, etc. Much of this information found its way to a sketchbook which I would bring to the photography sessions to share with those working with me.

Sometimes, when working to create imaginary relatives based on archival period pictures not much information was available, so we had to imagine it.

How much can a portrait really tell us about a person?

That is a question that photographers and thinkers have been trying to answer for a long time. A portrait certainly tells us about what happened between photographer and subject at a certain moment in time. This can involve asking the subject to assume specific pre-planned stock poses used frequently by the photographer coupled with pre-arranged lighting to produce a pleasing result. In this case the photograph conforms to formulas and tells about what is pleasing in portraiture, in addition to providing an idealized likeness of the subject. In other cases the photographer seeks to reveal an inner life in the subject.

How much does a picture of a person tell us about ourselves and what we look for when looking at pictures? Often we look at portrait photographs in order to recognize bits of ourselves in them, especially when we look at our own family pictures.

How much does a portrait photograph tells us about a person that can be glimpsed through or is articulated by the web of codes of gesture, lighting, pose, costume, makeup, all caught at what is conventionally thought of as a “decisive moment”? I do not have an answer for any of these questions, but I feel that my work complicates these questions and forces the viewer to think of the many personae that can inhabit a photographic portrait.

How has your family responded to the book?

Very supportive for the most part. Upon first viewing photographs of me as her mother and father, my mother shook her head and said something like “not at all like them.” I agreed but explained that I was not trying to, nor could I ever have achieved a close likeness. My father and brother are huge fans as are other relatives.

Do you now feel more strongly connected to your distant relatives, or further apart?

My work has been an incredible way to reunite family dispersed by 20th century catastrophes and normal movements of people. I feel a sense of a huge and incredible family around me now, whereas before I perceived my family as a very small group of people. My connection to my extended family through having done this work is not a given as before but a dynamic process that I plan to continue. The results of my research have generated a feeling of connectedness to a long line of people that I have been able to trace to the early 1800s.

As to further apart, I suppose my identification with Eastern European Jewry is much stronger now. As a second generation Latin American Jew I previously identified mainly as a Latin American.

What are you working on at the moment?

A couple of projects that I have been working on for sometime, one of which is more documentary in nature and has to do with the occasions when my in-law family meet to celebrate festive occasions.