In Between Insomnia and Scandinavia

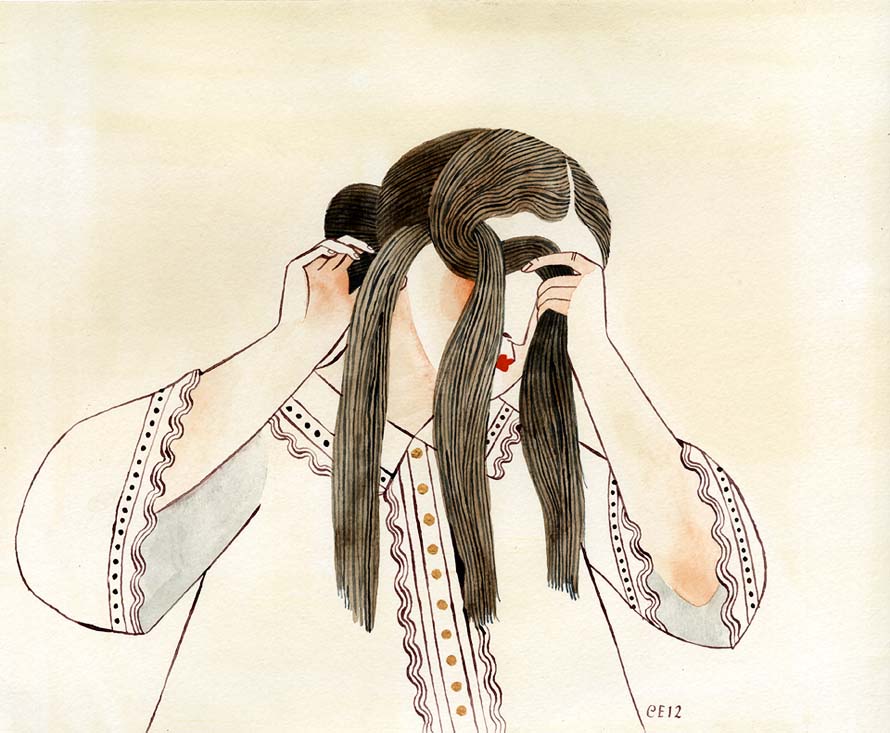

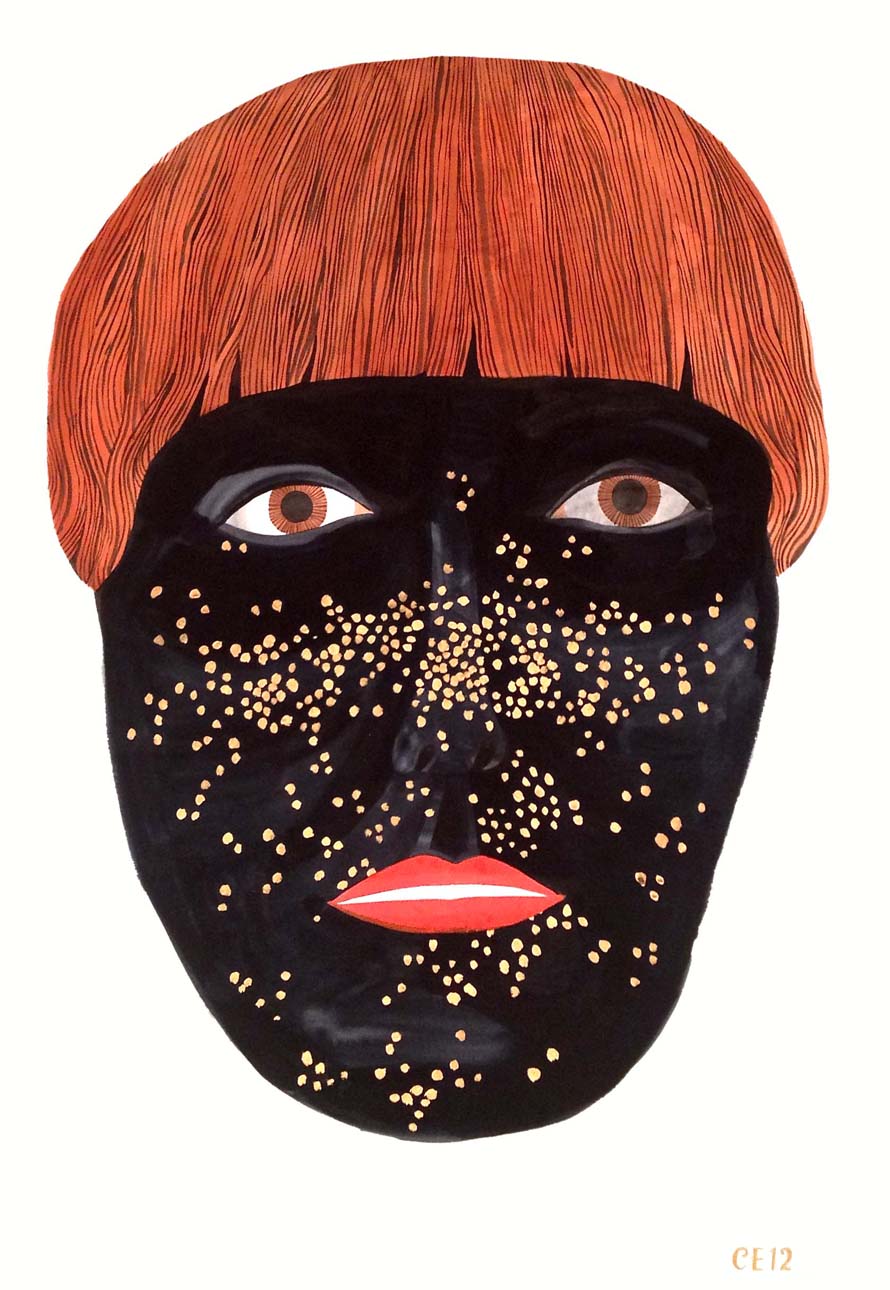

Inspired by depictions of motherhood in Norwegian historical novels, illustrator Carson Ellis hollows out a dream world made of joys and sorrows—familiar territory for many mothers.

Interview by Andrew Womack

TMN: You’ve said the novel trilogy Kristin Lavransdatter was an inspiration for this latest series. Are you depicting scenes from the books, or something else?

Carson Ellis: I read Kristin Lavransdatter for a long time. I took breaks between the three books to read other things, but I was sort of plodding through it on and off for nearly a year. For people who don’t know: It’s set in medieval Norway, written by Sigrid Undset in the ’20s, meticulously researched, sort of dry but really beautiful with its descriptions of snowy medieval Scandinavia—of men skiing over the mountains at night to bring news to their neighbors and thatch-roofed compounds and forests blanketed with reindeer moss. Continue reading ↓

Mush, Mush, the Sloping Midnight Line is on view at Nationale in Portland, Ore., through Dec. 9, 2012. All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

Anyway, I really internalized this book in a funny way—partly, I think, because I was reading it for so long and partly because I was pregnant for a lot of that time (I’m six months pregnant now) and the book deals a lot with the joys and sorrows and sometimes-intense burden of motherhood. I have a six-year-old so I know a bit about that already. And expecting another kid feels like the calm before the storm—lots to think and wonder about and anticipate. Lots of unanswerable questions and mystery.

So I’ve been in an extra-introspective state of mind lately and somehow the saga of Kristin Lavransdatter has really fed that. I’ve thought about Kristin a lot and dreamt about her. Also, like I said, the book is sort of dry but the world that the characters inhabit—Norway at the relative dawn of Christianity—is full of magic. Grown-up people live in paralyzing fear of trolls and sorcery. I loved that aspect of the book and it made its way into these paintings too. But no, they aren’t illustrations of scenes in the book. They’re the result of how the world of the book and all of this introspection and also my pregnancy-induced insomnia combined in my spacey, sleepy brain.

TMN: And congratulations!

Carson Ellis: Thanks!

TMN: You’re teaching illustration to teenagers at the Portland Art Museum. How did you learn illustration?

Carson Ellis: When I was in high school, I took a weekly art class for teenagers that was geared toward creating a portfolio for college applications. It was taught by an abstract painter in her studio in a neighboring town in wealthy Westchester County, NY, where I grew up. I think it probably cost an arm and a leg. Basically we all made the same portfolio pieces—a charcoal still life, a collage of a Fernand Léger painting, etc.—and I think most of the girls in the class (they were all girls for some reason) were just trying to round out their already probably amazing college applications with some art. Only one of them seemed to be really into drawing, like I was. (Karen Leibowitz, are you out there?) I was a really bummed-out stoner with abysmal grades and slim prospects for graduating, and this art class was the low point of my always very low week. I went against my will. It was mandated by my parents—punishment for something and also, I think, a last ditch attempt to help me focus on the one thing I loved and was good at: drawing.

Anyway, all these years I’ve held a weird grudge against that class. I felt like it didn’t take me seriously as an artist. Making a collage of a Fernand Léger painting was so far removed from anything that interested me creatively—it just made me angrier than I already was. And looking back, I think it was a missed opportunity. If the other students had been serious about art—other Karen Leibowitzes—it might have given me a chance to be part of a meaningful community outside of my high school where I was such a fuckup and to feel like art was a gift and a thing that connected me to other people. Or not. I don’t know.

But that’s the idea behind this workshop I teach anyway. I conceived it with my friend Dana Dart-McLean: We meet weekly for 12 weeks in the fall. Students have to apply and class size is really limited so most kids don’t get in—but the workshop is free for those who do, and they can come back every fall until they turn 18. Every year’s session ends with a big group show—essentially what we’re working toward the whole time. We pitched the idea to a bunch of different organizations around town and the Art Museum was the best, most supportive option (with the best, most awesome art supply closet) so we opted to teach it there and it’s in its fourth year.

TMN: Do you wish you had you as a teacher?

Carson Ellis: Man, I don’t know. I thought teaching would be easier than it is. It’s hard. I went into it wanting to help kids and for my own catharsis, but it turns out that most of my students are just fine and don’t really need my help. They’re mostly serious artists and grateful for the chance to spend time with other serious artists their age, like I’d hoped they’d be. But honestly, the few times that I’ve had kids in class that remind me of myself at that age—surly, stoned, hard to engage—I haven’t really known how to teach them. The student that most reminded me of my teenage self? I kicked him out of class for being absent too often and I think he probably hates me. He might even hold a grudge against my class until he’s in his thirties, just like I did.

So it’s more complicated than I thought it would be. Yet it’s more gratifying too. Even though I don’t always feel like I’m doing a good job, I always feel like I’m doing something good. And watching the way teenagers make art—pulling whatever they find out of the supply closet and using it with abandon—makes me happy and reminds me to do the same once in a while. I’m always so proud of the kids in my class. I’m excited when they make great work and grateful when they share hard things, which they do a lot, being teenagers with hearts often worn on their sleeves.

TMN: For the Wildwood art, did you do any actual location scouting, despite the locations not being real? Assuming the Impassable Wilderness isn’t real? And if it is, should we be concerned for our children?

Carson Ellis: The Impassible Wilderness is actually based on a very real place: Forest Park, a 5,000-acre woodland in the west hills of Portland. Colin [Meloy, her husband and author of the Wildwood books] and I knew we wanted to set the books there before we knew what they would be about. Before there were characters or a plot, we traced the boundaries of Forest Park onto a big piece of paper and made a map that we populated with real and imagined places and then revised and revised as the story took shape. (It’s now the map on the books’ endpapers.)

We live next to the park, which is just a big forest crisscrossed with 80 miles of trails, and Colin outlined a lot of the books while were walking in it. So yes, the Impassable Wilderness is real and really teeming with coyotes, though they aren’t the Napoleonic uniform-wearing, saber-wielding kind. Just the housecat-devouring kind. So you should be concerned for your cats. Some of the locations within it are real too: Pittock Mansion, for example, the seat of government in the books, is an actual, old historic mansion in the southern part of the park.

TMN: When you create album and book artwork for others, do you listen to or read their work before making the art? During? At all? Avoid at all costs?

Carson Ellis: Well, I always read a book I’m illustrating and listen to a record I’m making album art for—before, during, sometimes again and again. As for familiarizing myself with past works of authors or bands, I guess I don’t really go out of my way to do it. A lot of these collaborations have been with Colin and I know all of his creative work pretty intimately. The other books I’ve illustrated have been mostly for people I don’t know and had no contact with, so there wasn’t a lot of earnest collaborating. Each project was gratifying in its own way, but none so much as my work with Colin—because we’re married and it’s great to work with someone you love—but also because I suspect real collaboration between authors and illustrators yields more inspired books. So I don’t know if having knowledge of a person’s past work is as important to me as knowing them personally and being able to share ideas and talk about books with them. I think the key to a great book collaboration might be figuring out where the passions and creative vision of the author and illustrator intersect. As for music, with the exception of a funny gig illustrating a Weezer album cover many years ago, I’ve mostly worked for friends whose music I know and love.

TMN: So let’s settle it once and for all: Portland coffee or Portland beer?

Carson Ellis: I love both of these things so much that I can’t even choose. I’m mostly off the beer right now, being pregnant, but I pine for it.