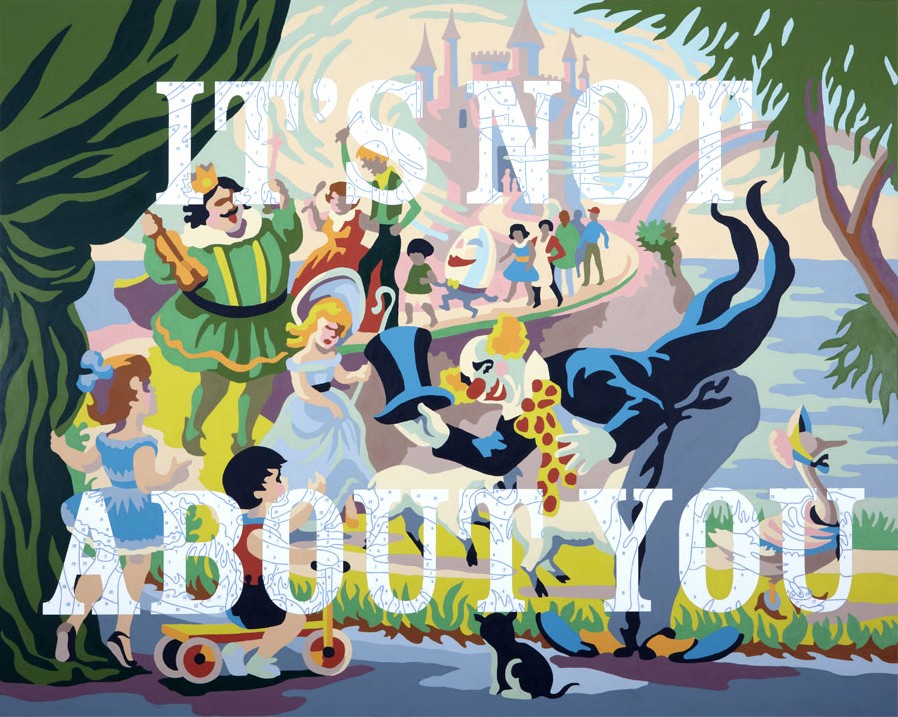

It’s Not About You

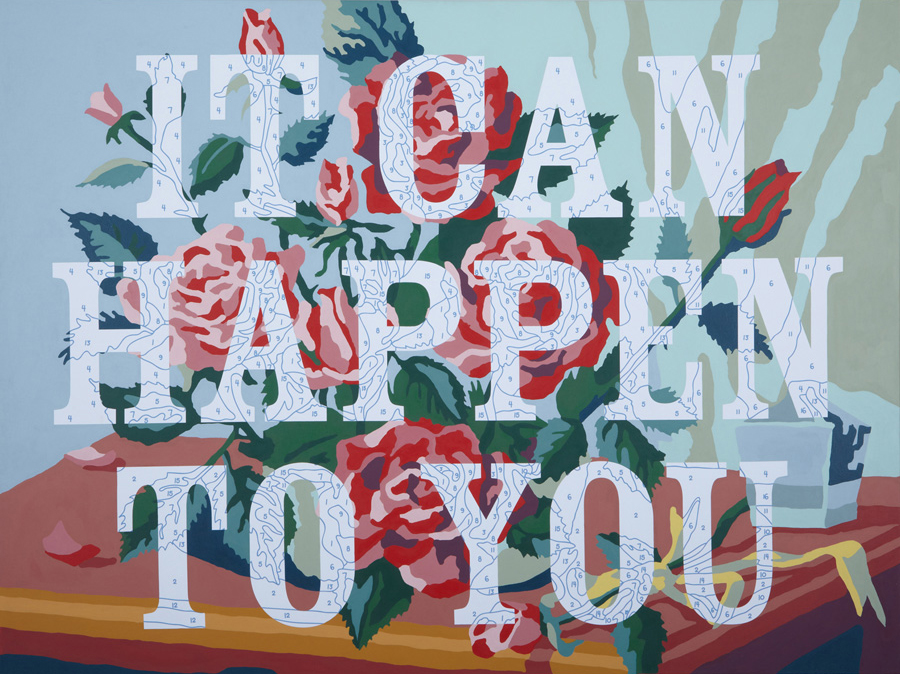

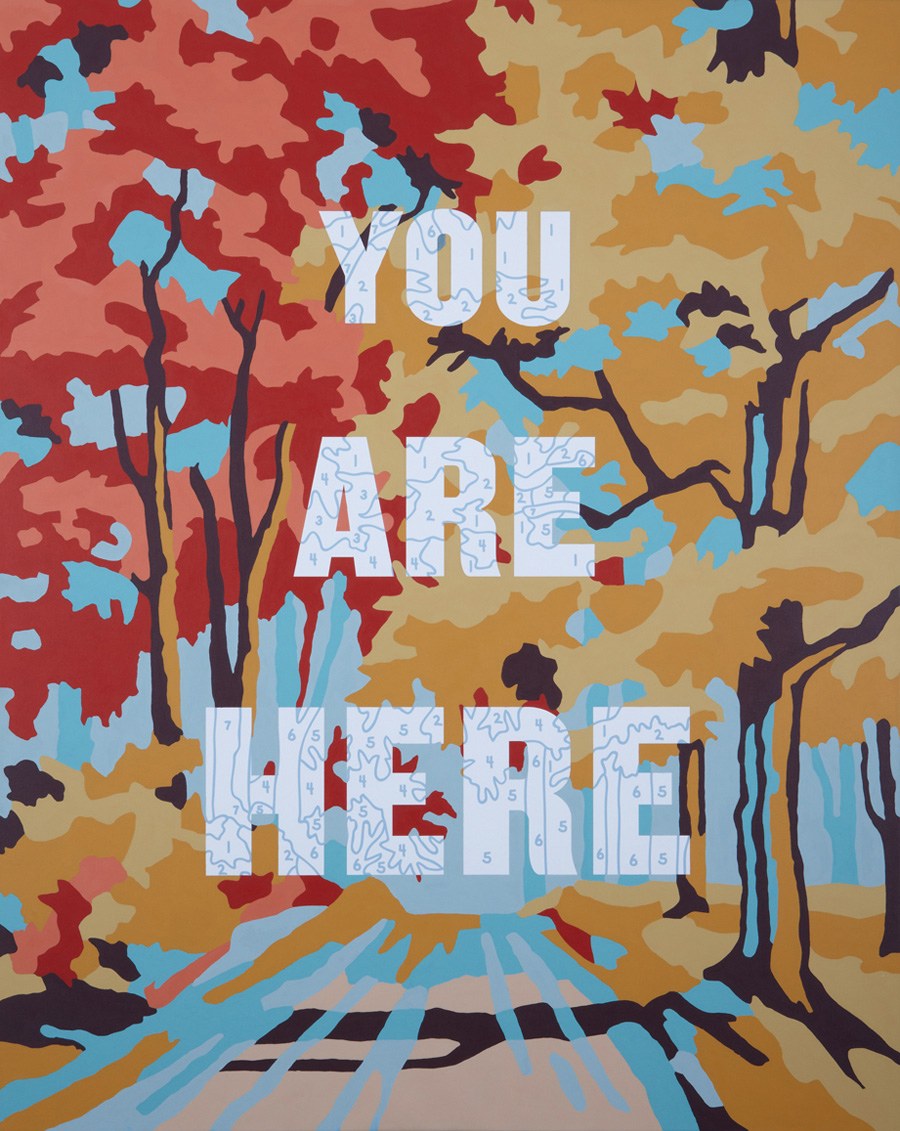

Trey Speegle’s paintings combine the highbrow and lowbrow with a nod toward Pop Art, overlaying meticulously altered vintage paint-by-number graphics with messages to the viewer.

Describe the concept behind the exhibit.

When I started making work for this show, I had several pieces, and many more planned, with the word “you” in the painting and/or its title, hence It’s Not About You. So much about the process of creating anything involves one’s ego to get going and get it off the ground. I had a realization at one point that I was not my ideas, that I don’t have to tie my identity to the ideas themselves—they exist on their own—and that the work isn’t about me as much as it is the viewers reaction to the ideas represented. That, and it does look good on a T-shirt: It’s Not About You. Continue reading ↓

It’s Not About You is on display at Benrimon Contemporary through March 5, 2011. All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

Where are these paint-by-number backgrounds from?

I inherited the collection of some 200+ vintage paint-by-number paintings from Michael O’Donoghue, a great friend and mentor and the original head writer of Saturday Night Live. He passed away suddenly, years ago, and his widow, my pal Cheryl Hardwick, gave the collection to me. Now I have something like 3,000 or so…

Why did you decide to use them?

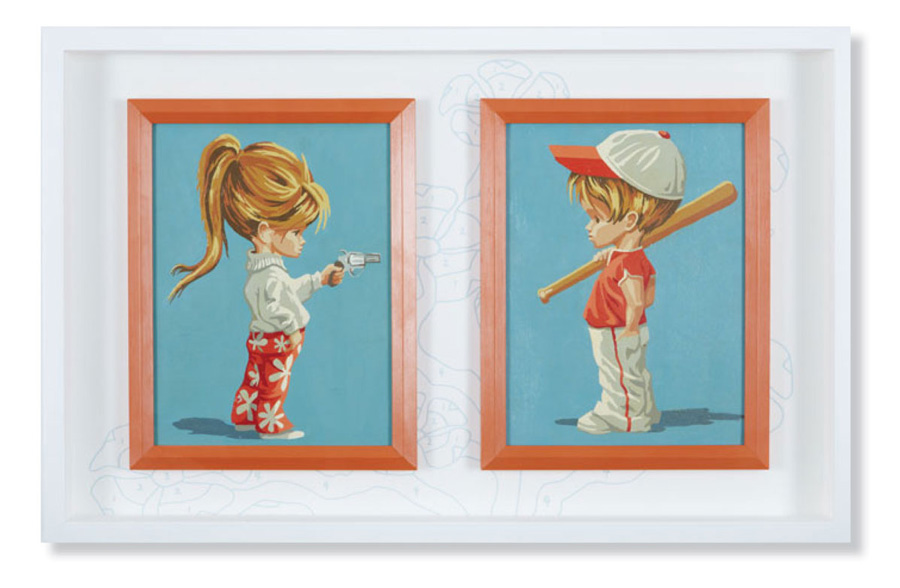

I had been making my own word art around the time, using found phrases and affirmations, and after living with the paintings for several years that filled four floors of hallways of my Brooklyn brownstone, I got the idea to merge them with words and use them as a jumping-off point to express my ideas about life and art.

What is the significance of the messages you’ve embedded in them?

They actually do mean a lot to me personally—and the very nature of the long process of mocking up the painting with words, redrawing the line work, printing it on canvas, stretching it, blocking out the lettering, mixing a new palette of sometimes 40 to 60 colors, and meticulously painting it in, make them take on even more significance by the sheer effort involved. I have distilled the words and made them into form by the time it is becomes real, so I have to really want to say something in order to go through all that.

Do the messages address the viewer, or the content of the paintings upon which they lie?

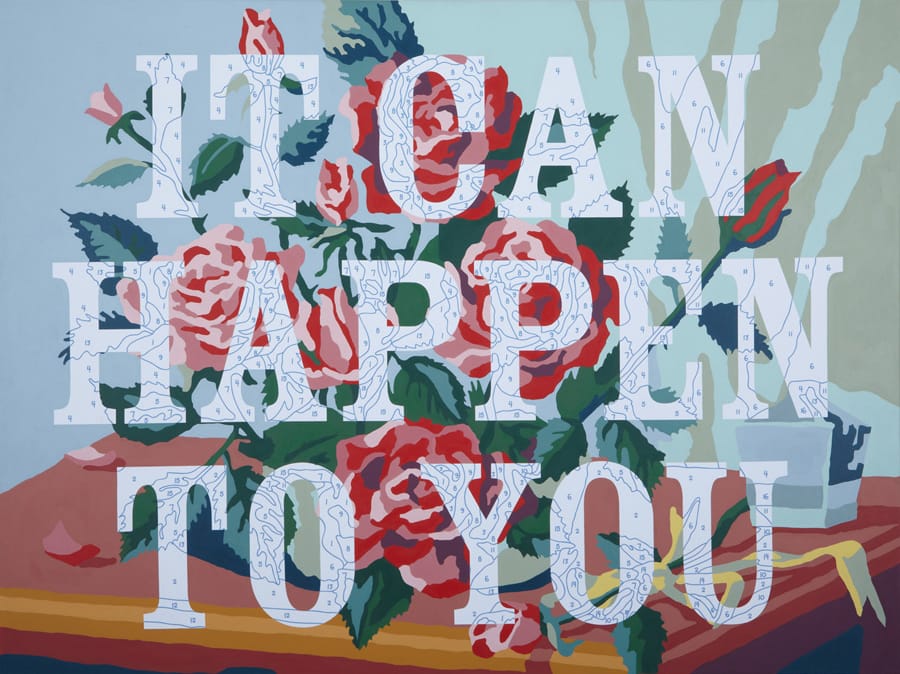

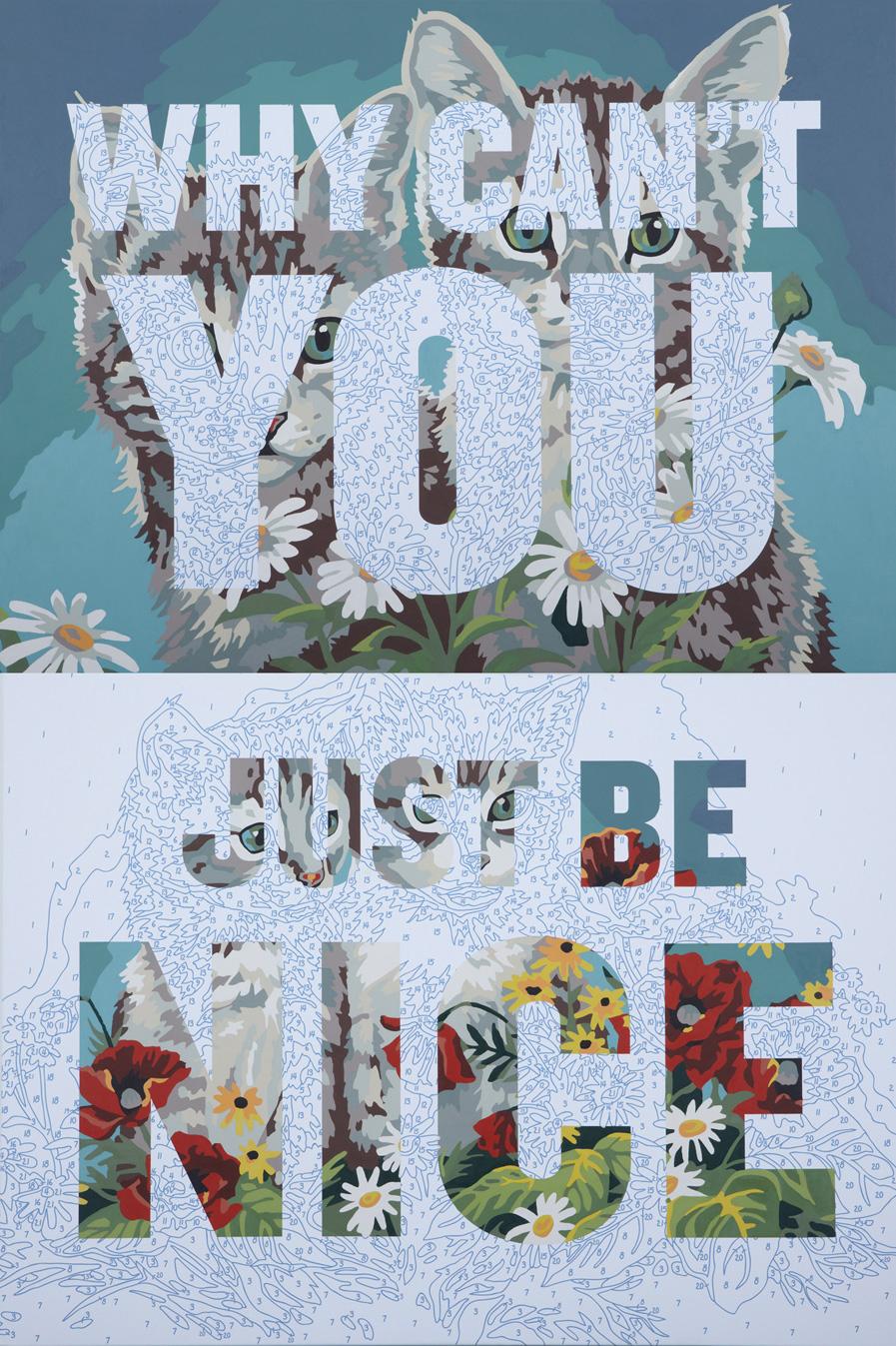

I use them as sort of a visual vocabulary and subvert their original meanings. The text can often go against the image; other times comment on the image or have no relationship to it at all—it just depends. The kitties in Why Can’t You Just Be Nice are more obviously connected to the words, whereas the roses in It Can Happen to You are more obtuse and the meaning is more open-ended.

Are these paintings intended to be ironic?

Again, it depends largely on the viewers’ own perspective. I don’t like them to be too cool for school or clever. Each has multiple meanings or perhaps none at all, if you are left cold. I try to get them to sit right at the intersection of profound and banal. You Are Here is a real-time self-locator and an existential statement in one.

You’ve collaborated with Anthropologie, Stella McCartney, Fred Perry, and others. How does your explicitly commercial work compare and contrast with your artwork?

Yes, I’ve used my work to create shirts, bags, rugs, pillows, wallpaper, plates, soapboxes, bed linens, etc. The fact that paint-by-number kits started out as a commercial venture (and I believe now that they predate Pop Art as the first American Pop paintings) makes them want to naturally go back that direction. What I do is, I take my own work and apply [it] to production items, rather than the other way around, which is what I’m doing when I make art. I often cite Jasper Johns’ credo, “Take something. Do something to it; do something else to it” as the formula for my work. It can also be a recipe for applying my work to items for mass consumption. So, conceptually, you could argue a few points with this: What is art? Who is the artist? Is the artist’s own hand required to make Art with a capital A?

What are you working on now?

I have ideas for the next four or five exhibits. I keep distilling each piece and then seeing where it fits, thematically or at all, in the context of what I want to say. The phrase I’m most excited about informing a new exhibition is “Originality is overrated.” There is a lot I can put under that umbrella!