Juicy Paint

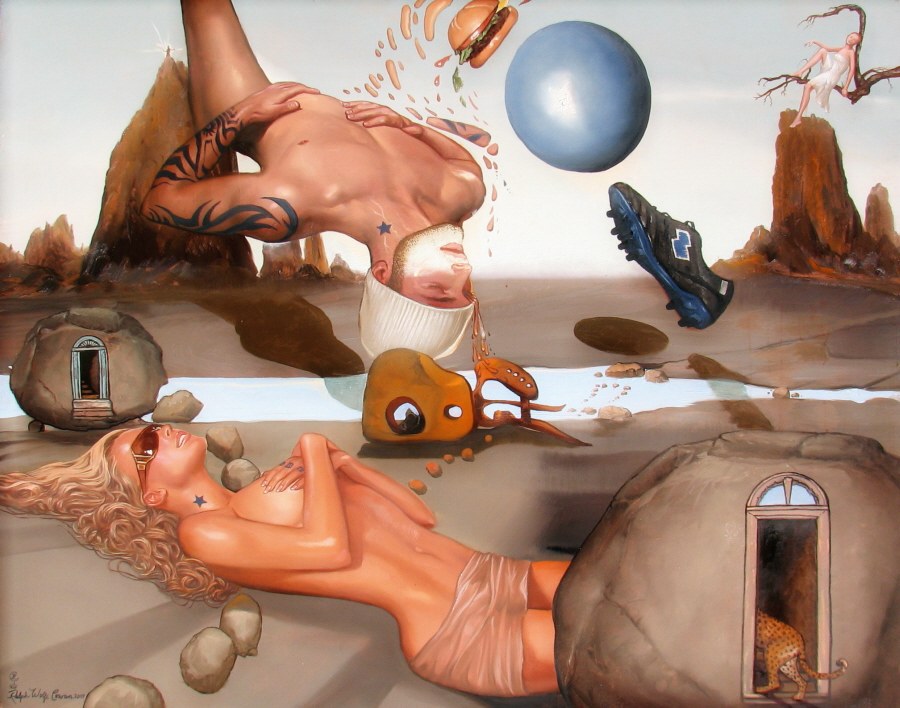

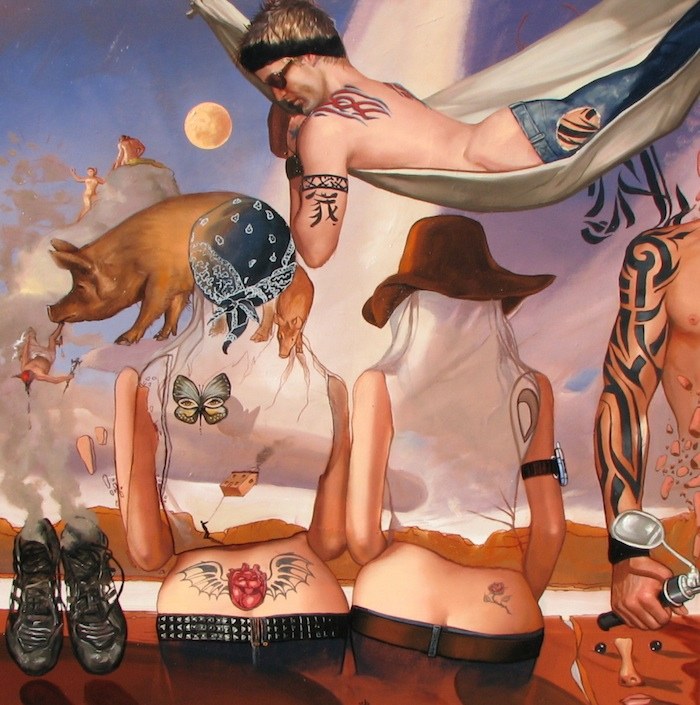

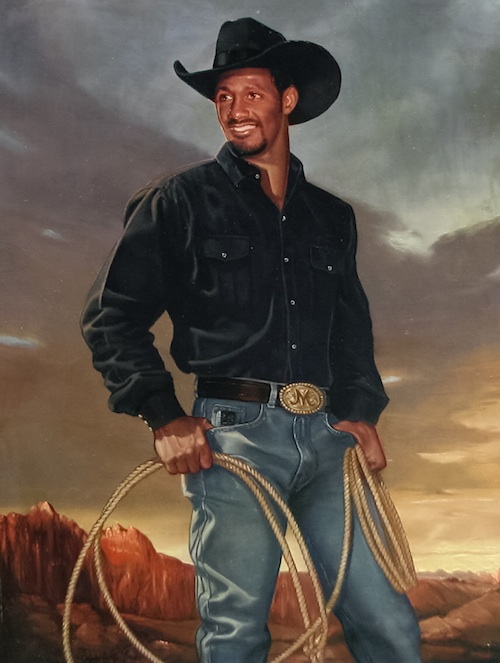

If Salvador Dalí and Paul Rubens painted Saudi kings while eating caviar and listening to Elvis, the collaboration might look like Ralph Wolfe Cowan’s portraits of heads of state, iconic celebrities, and buff, young models.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

A full-length portrait signifies social, economic, and political supremacy, though the painting’s proud tranquility often belies complexity and controversy. Love them or hate them, Cowan’s subjects lead the good life and his paintbrush dutifully reports their triumph. Read the interview ↓

Cowan’s current show, “Rough Edge,” is on show at Vertigo Art Space in Denver through July 30, 2010. All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Artist interview

When did you start painting portraits?

I started painting when I was four years old. A midshipman had left a set of oil paints in a wooden box in my church and I took them home. I did a portrait of my mother and I got a dollar. I had never seen more than a nickel or a dime. I thought I was rich. The minute anybody would come to visit my mom, I’d say, “You want your portrait painted?” And they’d say, “Hey, kid, I don’t have time.” I set up an easel in my room and I’d run in look at them while they were with my mom and then go back into my room and paint something. That’s when I developed a photographic memory. I can see something and keep it in my head for months at a time.

How did it become a profession?

I traveled during my young life because I loved it. I was in nightclubs every night because I loved it. In those days all my energy went everywhere. People would say, “Well, you must love painting.” I didn’t love it. I loved the outcome, the checks, but 30 years ago, I had a spiritual teacher who said, “R.W., the joy is in the work,” and I said, “No, no the joy is in the outcome.” All those years I was painting I had a certain amount of fear about how it was going to turn out. She convinced me the talent wasn’t really mine, it was God’s talent, and I got really resentful, but after a few days I said, “Well let’s try it that way.” And it’s been absolutely amazing. Now I just pick up the paintbrush and the magic starts.

I have a secret code word with God: “juicy.” When I was in New York studying when I was 16, I didn’t feel I was getting much out of school, and I went over to copy at the Metropolitan museum. I was fascinated. I put up an easel and I’d paint there all day. I went through the Rembrandt room and I painted those and when I got to the Rubens room I thought, my God, there’s nothing better! He was the best painter that ever, ever picked up a paintbrush. He was the most juicy painter, with the greatest color schemes. And his student, Sir Anthony Van Dyke, is my favorite portrait painter. I like to paint all the modern people in this fashion.

You mean in the Baroque tradition, or with some classical interpretation?

When I say I’m looking for a “juicy” painting, I want something with some glory in it. Like one of those Saudi Arabian kings up on a horse with the wind blowing and his robes and there’s a falcon on his arm—glorious stuff going on.

A guy who was writing an article for a portrait painting magazine wrote that I’d painted more reigning monarchs than anyone in history. It wasn’t because I was that good, though, it was because of airplanes.

How many reigning monarchs have you painted?

I have to watch it because I’ve spent my whole life exaggerating. I’ve painted 12 and a half heads of states—the half because I painted a crown prince who was going to become king.

And are you attached to these people? Do you have favorites?

I have this one rule: I don’t let anybody say anything unkind about anyone I’ve painted. It’s very trying when it comes to someone like Donald Trump.

You have a sense of loyalty to the people you paint?

I do have a sense of loyalty. I also feel a kinship. I feel like everybody I paint is like my brother and sister, and the children are my own kids. This weekend we were up in Lexington, Ky., and I painted a lot of people there. One governor’s wife, I painted her children and she spent the whole evening talking about how one hand fell across the lap, and one hand of her little girl fell across the other lap, and it went on and on and on, and I had to be incredibly polite. It is a good painting, but you have no idea how much they mean to other people.

What do the portraits come to mean to people?

They become the most important thing in their life. One time I was painting this count and he had twin portraits of him and the contessa. They were both in white. They had a fire in their apartment in New York. Everybody was rushing around in their pajamas to get the most important thing, and he grabbed a painting of mine. Unfortunately, it wasn’t hers, it was his, and it ended the marriage.

It sounds like he was really attached to the painting.

She saw it as total self-centeredness. It would have been much cooler to have grabbed hers first, then his.

Why do people have this desire to be painted?

I find that every single person has a completely different reason. People say it’s about arrogance or whatever, but it seems that the people who are the most arrogant are the ones who worry, “What will people think?”

Some of the people you’ve painted are pretty controversial—Imelda Marcos, H.M. Sultan of Brunei. Is there anyone you won’t paint?

I turned down Gaddafi and Castro. Imelda Marcos knew these people. She had introduced me to several kings. I discussed these things with the kings themselves and with Imelda.

Yes, but Imelda herself is controversial and allegedly corrupt.

I know and I just think she is the coolest gal. She is so spiritual and loving. The stories that you hear are not the stories that really happened.

Right near the White House there are some of the biggest slums in the world. You don’t think about that until you are talking to these other people. Imelda built a whole city and moved all the slums outside the palaces.

Then it’s not so much that you’re not concerned about a certain person’s leadership, you feel your personal relationship gives you a different version of the story?

Imelda once told me, don’t ever pay attention to what you read. Ask everybody—they’ll be very happy to tell you; because they’ve chosen you to be their portrait painter, they want to talk to you about all of these things. When you’re around political people it all turns out to be political anyway.

Everybody that America thinks they don’t like, a few years later they do like them. It’s hard to keep up with who we’re supposed to hate and who we’re not supposed to hate. That bothers me spiritually.

Why shouldn’t I have painted Gaddafi? At one time he was a nice-looking guy. I could have won him over and he would have been like, “I can’t hate America cause I like R.W.”

When you go into these situations, it’s as an American?

Yes, and I see [the person I’m painting] more than our ambassador does. The ambassador comes to me and asks me, “What’s he really like?” That situation was interesting to me; I say “was” because I haven’t painted anybody in years. I did do the King of Jordan. We were in Washington and I did a drawing of him and his whole family. Later on we were going to do a full portrait of Queen Rania, and all of the sudden there was an announcement in the paper that George Bush had done something against the Palestinians, who are friends with the Jordanians, and they canceled the whole trip and I got a letter that they canceled the portrait.

In terms of subject and topic, your “Rough Edge” work is obviously very different from commissioned portraits. What’s the inspiration?

When I paint these “Rough Edge” ones, these good-looking kids with their tattoos and all that, they might become my clients later on. I sort of see it as Abercrombie & Fitch in the middle of Salvador Dalí.

Dalí is the most sensational surrealist ever. I loved him when I was a little kid; I met him in New York, I found out he lived in this little hotel and I would stay outside—other people stalked movie stars and for some reason I stalked him.

You can’t avoid him. I remember once I was painting a lady who had been the mistress of one of the kings of Norway. She was really beautiful and I wanted to paint something that showed extreme heat and extreme cold, so I had a whole thing of ice mountains behind her, and then I had her sitting against this lion and I had his mane on fire. It was sensational. I thought I had totally created it. The very next afternoon, I was up in a lady’s apartment, and she had a full, huge, original Salvador Dalí and it had these giraffes in it with their manes on fire. He painted it in 1931, the year that I was born. I had never seen that painting, but you can’t avoid him. Whatever you want to do that’s original, he’s already done it.

I read that you painted a portrait of a man who mugged you.

A guy grabbed all my chains off as I was getting in my little convertible. I was chasing the guy to run over him. The police stopped me and started asking me all these questions. I said, “I can do a portrait of the guy.” I came back to my studio and I drew the whole thing, and the next day I put it in color and put a gold frame on it, being that I’m a professional. There was a guy there with a TV camera doing something else with channel 5, but they put it on television that night and CNN picked it up. This is a good story if you think you’re having a bad night. Anytime I see someone having a bad night, I say, “Let me tell you about the night that something bad happened to me and it turned into two million dollars of publicity.”