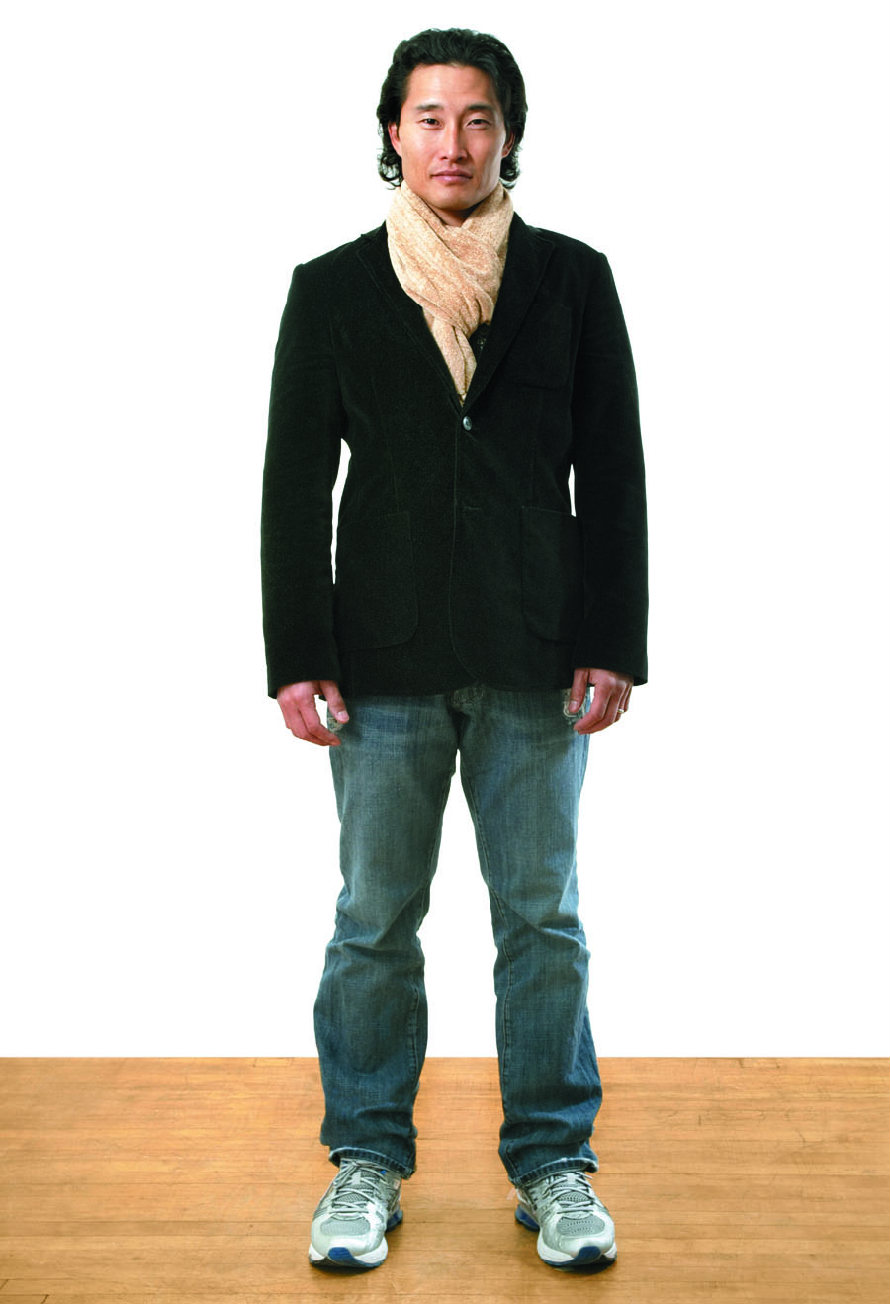

Kyopo

Portraits and interviews from a new book that showcase the Korean diaspora, from novelists and athletes to actors and retirees.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

TMN: What inspired this project?

CYJO: It was in 2004 when this project started. After visiting bookstores during this time and not seeing photography books that covered the Korean culture and modern contemporary issues, it felt necessary to fill this void.

Growing up in the US where my community of friends was not specific to one ancestry, I was also curious to understand how others who shared the same ancestry positioned themselves in their societies and how they identified themselves being both American and Asian. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved. The following discussion is compiled from a conversation that took place over several emails.

Interview continued

TMN: How did you find your subjects?

CYJO: My first participant was a random stranger I met at the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, Sebastian Seung. He happens to be an MIT professor of neurological and cognitive sciences who has spent many years studying connectomes—the wiring of the brain. After his participation, he recommended a couple of people, and they recommended others. I met other participants through chance meetings, which also helped to keep the group spontaneous and organic.

TMN: Beyond all being people of Korean descent living outside Korea, is there anything that you believe links or connects your subjects?

CYJO: Because they all have had bi-cultural or multicultural experiences, they are receptive and respectful to other cultures and/or differences. Many related more to a global and unified human race than a culture-specific race.

TMN: How did your subjects react when you told them about the project?

CYJO: Most of the subjects were intrigued and interested in participating in the project. It was something they had never been asked to do before. It was not easy for all participants to define their identity and their relationships with their heritage.

There were some small business owners who migrated in the ’60s and ’70s who weren’t initially receptive to participating or who had declined the opportunity. They worked at gas stations, drove taxis, owned small delis and laundromats, etc. Some small business owners didn’t think they were important enough to be part of it. This was contrary from how I felt; to me they have been vital in helping the economy and contributing to their societies. They sacrificed so much to achieve that American dream and definitely deserve recognition for their hard work and contributions.

TMN: Why shoot them in the studio, in front of the same white background?

CYJO: In order to compare and contrast individuals more easily, a uniform background was maintained. Uniformity could be created in my studio with controlled lighting. This also allowed me to play with pictorial flattening.

TMN: What has the project taught you about recent immigrant experience and that experience generations later?

CYJO: In many cases, priorities and dreams vary with recent immigrants compared to those who have lived in countries generations later. Recent immigrants tend to focus on the immediate priorities—acquiring a house, having a healthy and educated family, having health insurance and a steady paycheck—which makes perfect sense. Most don’t have full command of the language and culture of the country they’ve moved to. There are many parents from the first generation that want the best for their kids. And having them become a lawyer, doctor or engineer does represent the best through their perspective at the time.

Thanks to the hard work and sacrifices of the first generation, those that have lived in a country generations later are able to live more comfortably, and have command of the language and culture of this country, a culture that defines them just as strongly if not more than their ancestral culture.