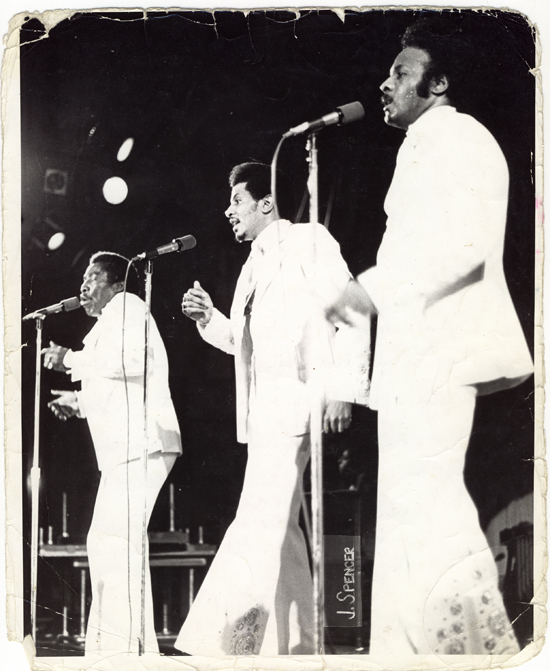

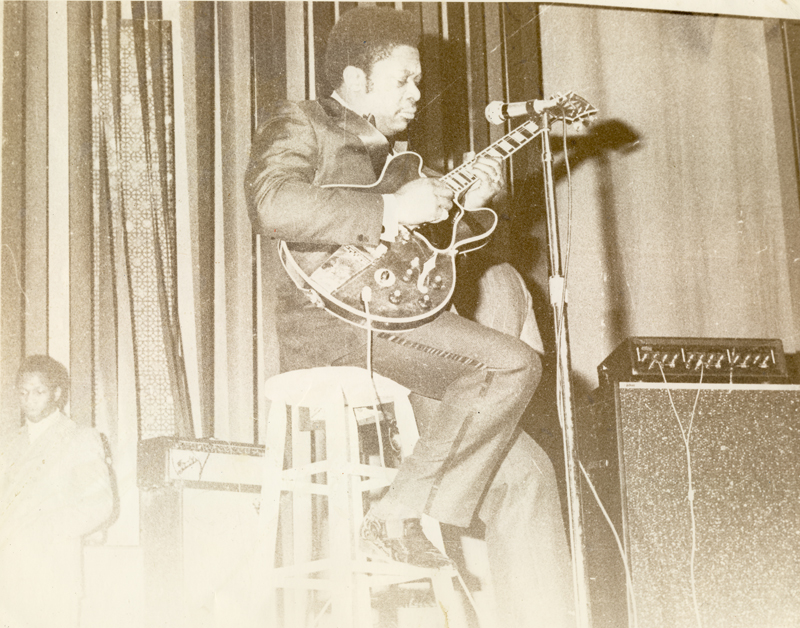

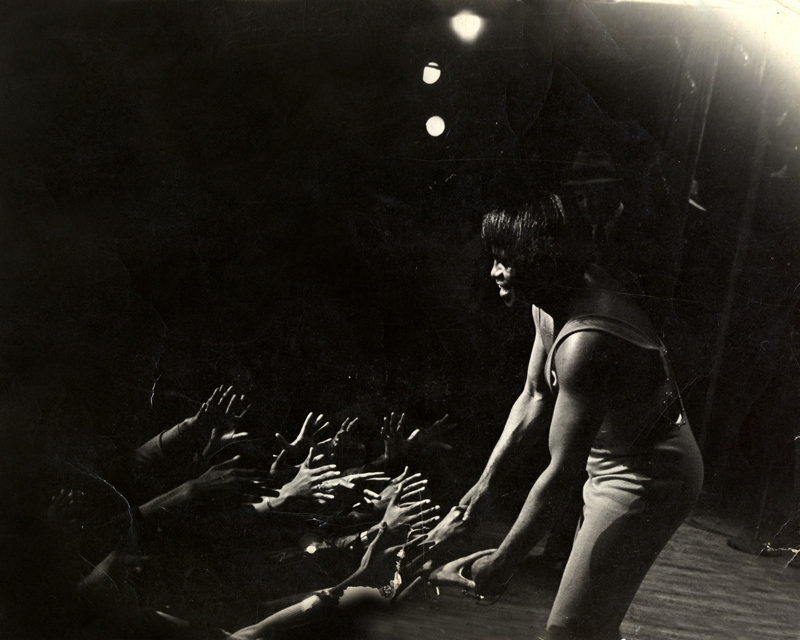

Legends in the Making

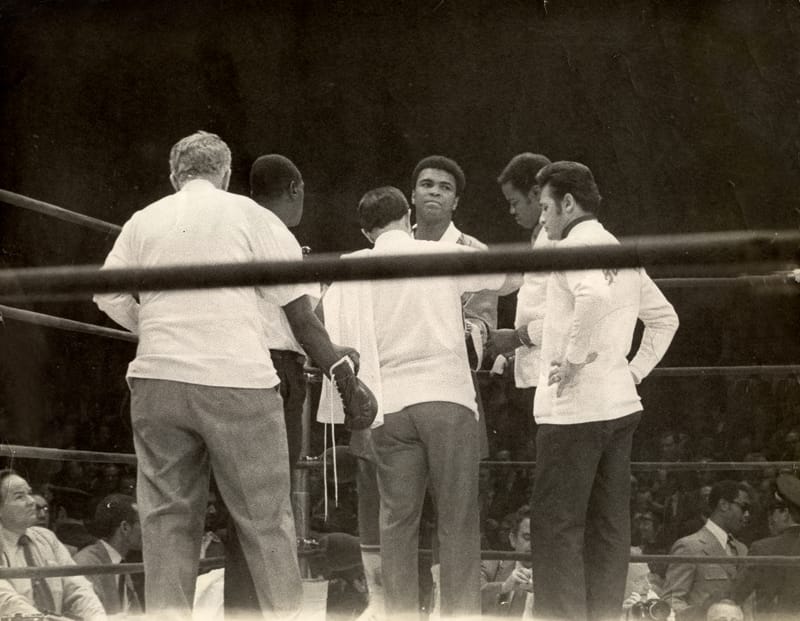

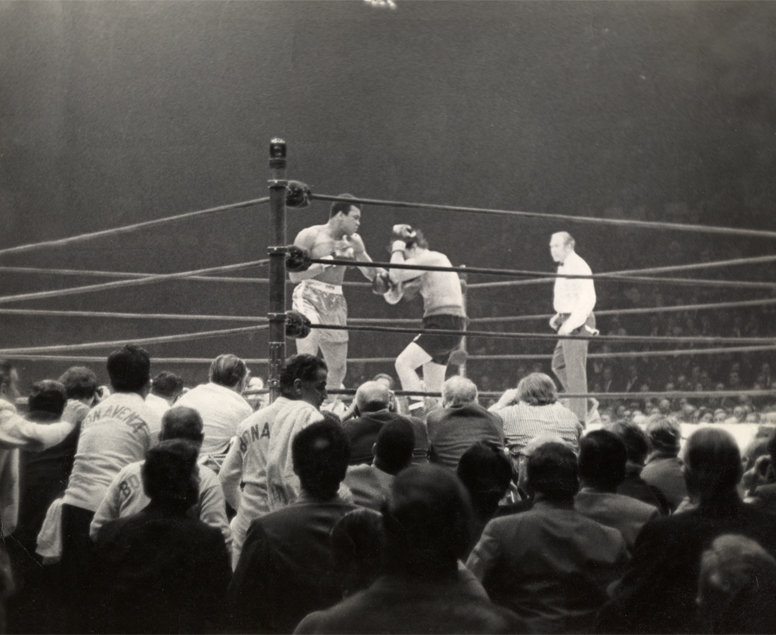

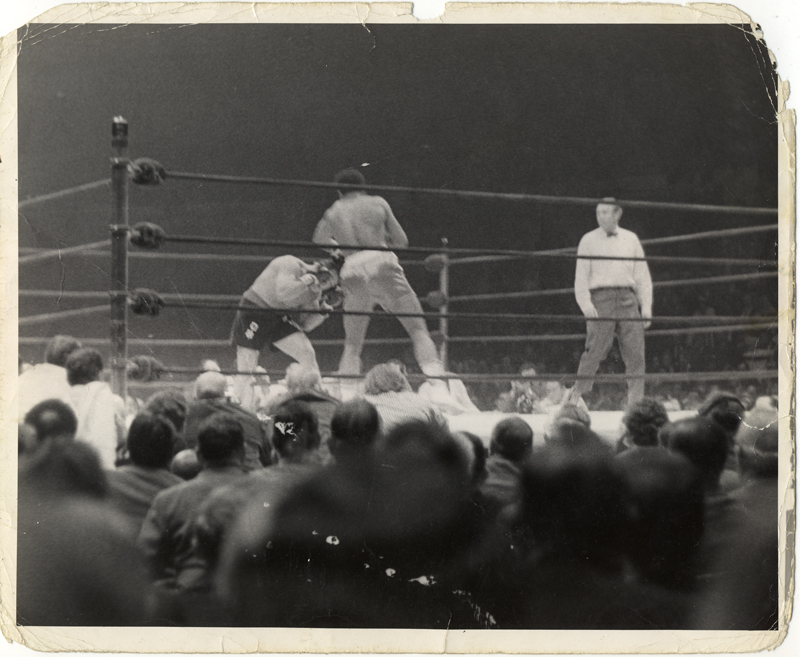

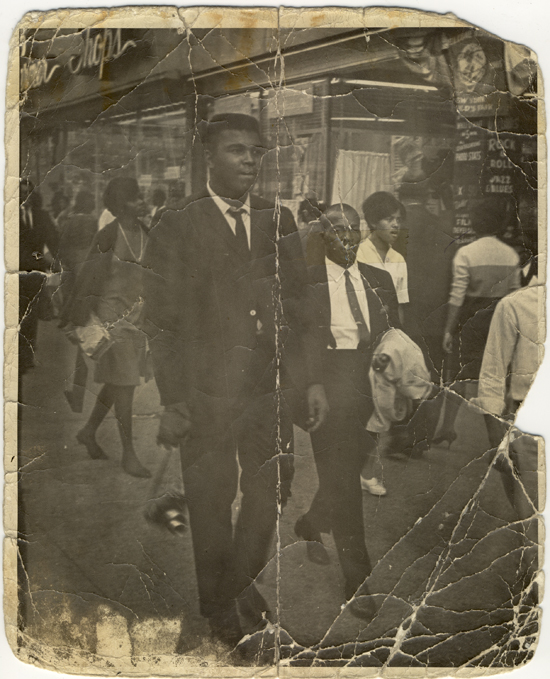

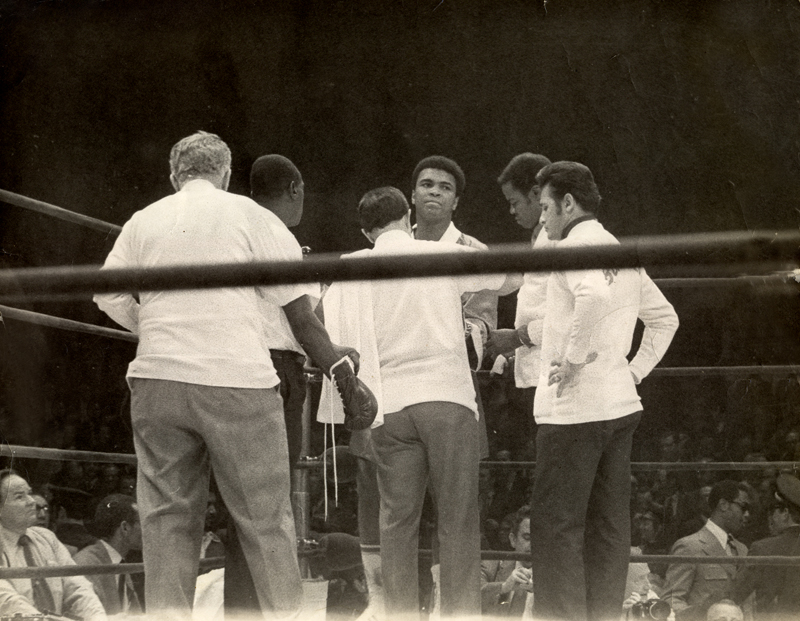

Originally from Harlem, James Spencer has lived a freelance photographer’s dream. He shot regularly at the Apollo during the ’60s and ’70s, rode around Manhattan with Muhammad Ali, and traveled as James Brown’s personal photographer.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

You’ve photographed so many wonderful people. How did you get started as a photographer?

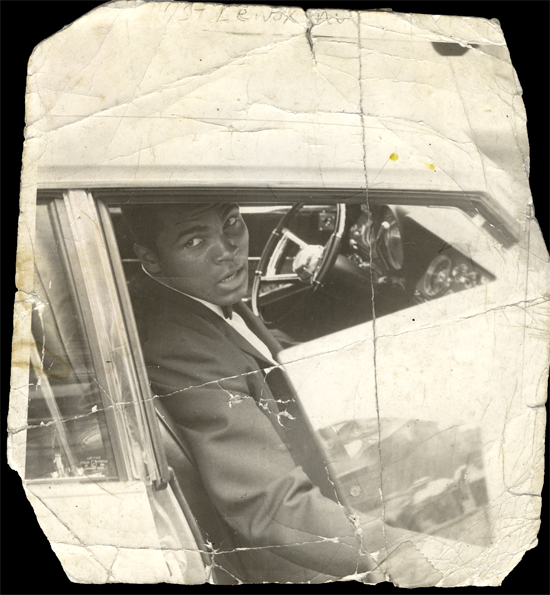

I took Muhammad Ali’s picture on the street one day and he took to me. He was Cassius Clay then. He gave me my first $500. That was like $5,000 back then. I guess he saw the little jim-jam camera I had. He said, “Learn photography and go into business for yourself.” So, I bought a book called How to Develop, Print and Enlarge Photos. I read that from cover to cover. It seemed so easy; I didn’t think I understood it right. But that’s the easiest part of photography, how to develop and enlarge pictures. I knew I wanted to do this for myself. From then on, every time [Ali] would come to Harlem, he’d see me and wave at me to get in the car. He’d put his fists up and ask, “You got any pictures for me?” I’d show him the photos I had in my attaché case and he’d give me some money. Then we’d ride around Harlem and I’d shoot more pictures. Continue reading ↓

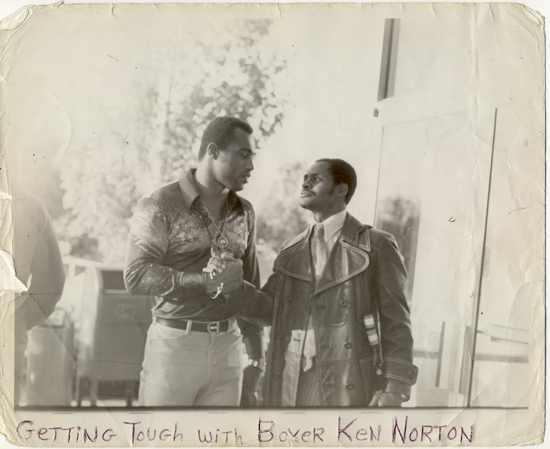

All images used with permission, © copyright James Spencer, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

I can’t believe you just met Ali walking down the street.

When I’d walk the street with Muhammad Ali there would be a crowd around him. If I saw a little boy across the street I’d say, “Come here a minute” and they’d come into the middle of a crowd and see Ali. [The kids] were shocked. I’d take their pictures with him and get their addresses. Then I’d develop the pictures and send them to [the kids]. I ran into a guy last week who said that he remembered me shooting pictures when he was about five years old. He said, “Man, Brother James, you were downtown and you called me to take a picture with Muhammad Ali and I froze up. I never got a picture.” He hates the fact that he never took the picture.

Did you typically just go out and shoot photos of people on your own?

I was a freelance photographer. I would take pictures and then sell them back to [the artists]. I’ve been blessed because famous people like [Ali] have been handing me money like that for a long time.

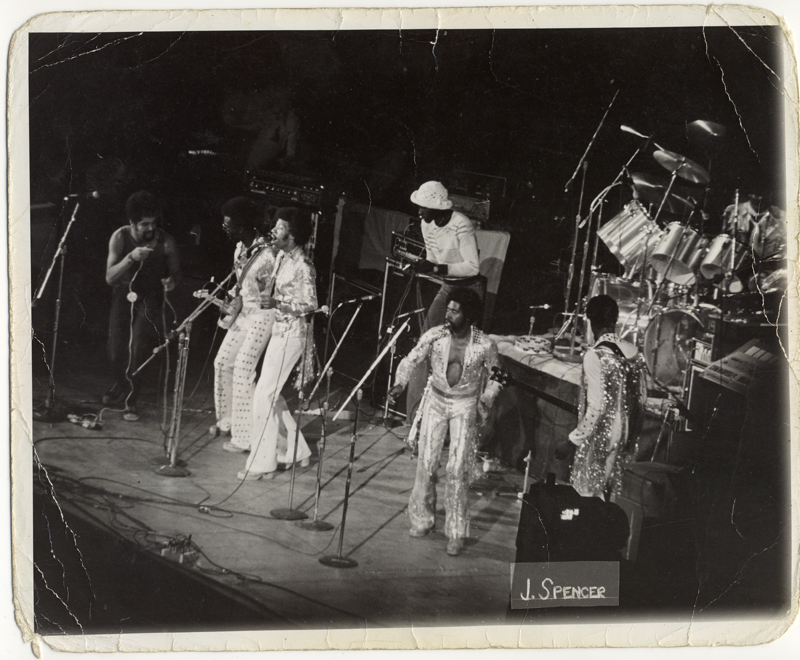

How did you end up working for James Brown?

Around 1972, I was into martial arts and Charles Bobbit was one of my instructors. He became James Brown’s bodyguard and then James Brown’s personal manager. I’m from Harlem, but I was doing photography in Brooklyn and [Bobbit] ran into me on Broadway one day and he said, “What are you doin’?” I said, “Well, I’m doin’ photography.” He said, “Are you a professional? Because James Brown needs some new pictures.” He told me to come to a studio that night where James Brown was recording. As James Brown came out of the Polydor offices, I took some shots without flash so as not to disturb him, since he was talking to some people. I went home, developed the pictures that night then came back and left about 16 or 20 pictures at his office. I went back a couple weeks later and Bobbit said, “Damn, Mr. Brown loved those pictures.” He gave me five $100 bills for the pictures I’d left and he gave me a down payment for film and things. [He wanted me] to shoot James Brown while was doing a week at the Apollo starting the next day. I shot the show for a week and he used seven to 10 of my pictures for the inside cover of his album Get on the Good Foot. I took all the photography on that album—it was the first work I did for him. I started traveling with him off and on and shot a couple more albums.

What was James Brown like?

He was funny when he wanted to be, but he was also very serious. He was always talking about racial issues and business. He felt that at different times the powers that be had hampered his progress. He was very strict with his workers. He fined his band like he was keeping a beat; he’d open his fingers—$10, $20, $30, $40, $50. He’d fine you $400, $500, $600 according to what you did. Make a wrong sound—that could be a $500 to $1,000 fine. It was a business and he was a business man. He’d tell you, “I’m 10 percent an entertainer and 90 percent a business man.”

Did you ever have had any problems with him?

No. He always liked to mention to people, “This is my personal photographer, Mr. Spencer.” He liked me a lot because I wasn’t getting high, drinking, or smoking. I was punctual and I wasn’t clamoring to follow him around. Once I went with James Brown to his house in Georgia. When we were coming off the plane, he introduced me to Jimmy Carter, who was [then] the governor of Georgia. The press was out there shooting pictures and he said, “Mr. Carter, this is my personal photographer.” When I got back to the office [in New York], Reverend Al Sharpton was there with some other people and he said “Spencer, we thought that you were lying when you said you were going to James Brown’s house.” I pulled the pictures that I’d taken, and I showed them. It was strange because I hadn’t realized that people were doing that jealous thing and were dying or vying to hang out with [Brown].

So, he liked you because you weren’t charmed by fame and the spotlight.

I was a poor dude from Harlem from a big family. It’s not that I didn’t respect people; I just didn’t think any [celebrity] was over me. I’m an Aquarius, I just stand back and I don’t like traveling that much. One time when I was working for James Brown I was in the air three times in one day. I wasn’t traveling with him all that much but whenever I was I’d get hundreds of pictures in a week.

Who else have you shot?

I knew this tap dancer who was in charge of the front door at the Apollo, so I had access. I shot Lionel Richie with the Commodores, I shot BB King. I’ve shot so many people. I photographed Martin Luther King, Jr., when he came to New York after receiving the Nobel Peace Prize. I didn’t get to talk to him but I was shooting right near the stage.

Who did you always want to photograph but didn’t?

I went with Al Sharpton to meet Duke Ellington. We went to his house and his sister said he’d gone to the hospital the day before. He died before we could visit him at the hospital. He was one of the main people I really wanted to talk with.

I love that picture of you with Melba Moore.

Al Sharpton shot that picture. I was doing photography for Sharpton’s National Youth Movement. I’d met him in James Brown’s office and I recognized him because I’d just moved into his building in Brooklyn. He knew Melba Moore and he recognized her on the street. I took a picture of Sharpton and Melba, and he took a picture of me and Melba.

Where are your photographs now?

I lost a lot of my negatives during travel or while moving around the country. I find pictures in magazines I know I shot. I’m missing thousands of negatives. I used to roll my own film and I have shot so many people: Jackie Robinson, Sugar Ray Robinson, Joe Lewis, people like that. There’s a lot that I’ve lost. I had pictures of President Johnson in Harlem when he was campaigning. There were just a few pictures I was able to hang on to and then I just came across a pack of negatives. Once I found them, we printed some of those negatives to show in the video.