Loss of Home

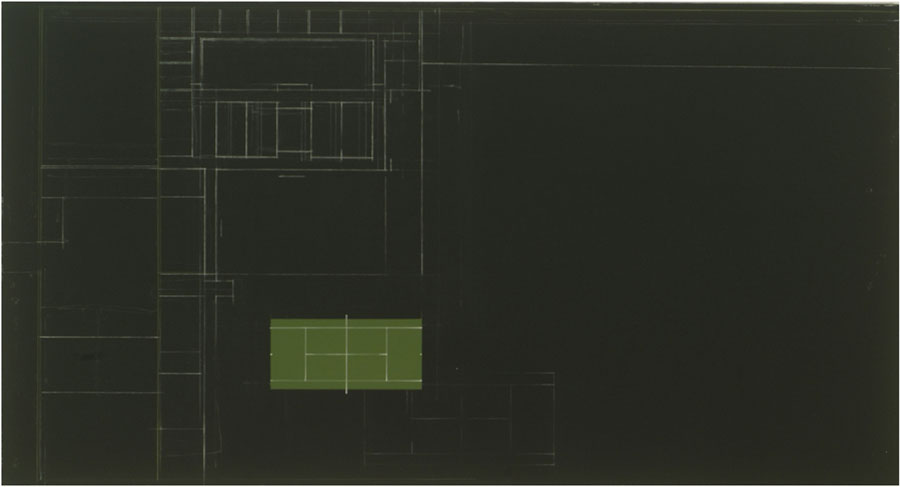

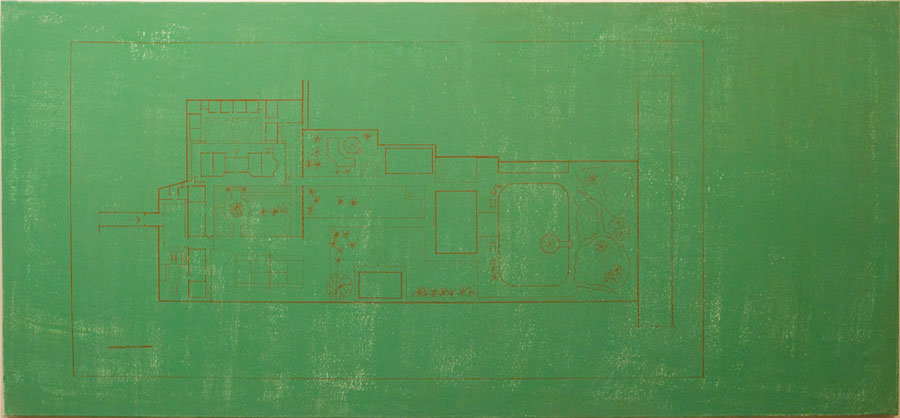

David Diao’s paintings of Chinese characters, recreated floor plans, and an isolated, ominous tennis court illustrate not only where the artist has been, but who he’s become.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

The focus of the show is the house in Sichuan your family was forced to leave because of the Communist takeover in 1949. Why tell this story now?

I was asked to do a show in China last year and I realized my usual subject, with its references to modernism as it occurred in the West, would not read there. So I wracked my brain to come up with something that could engage them. And that catapulted me into actually taking up the subject.

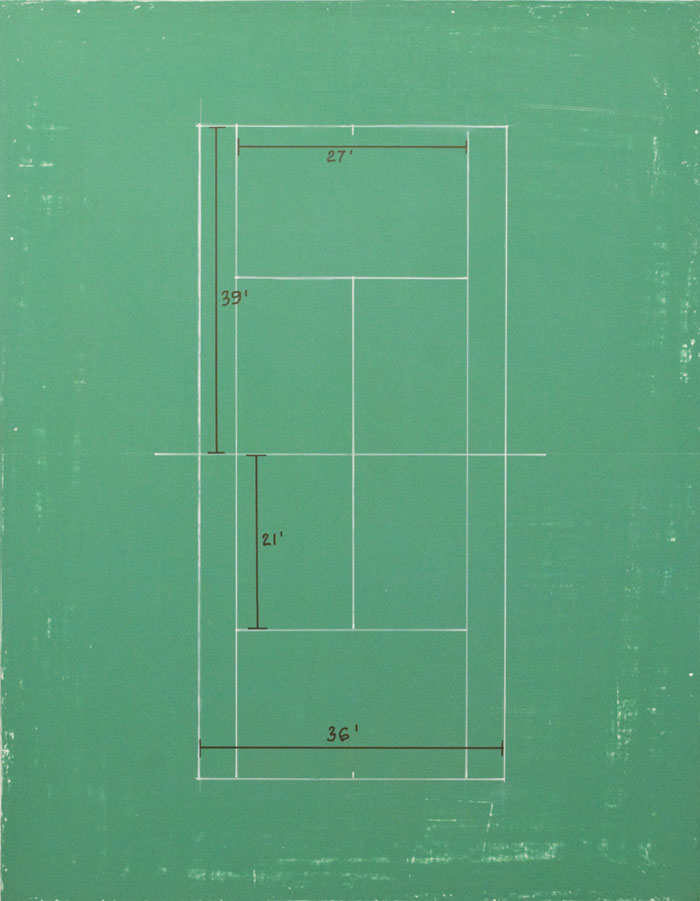

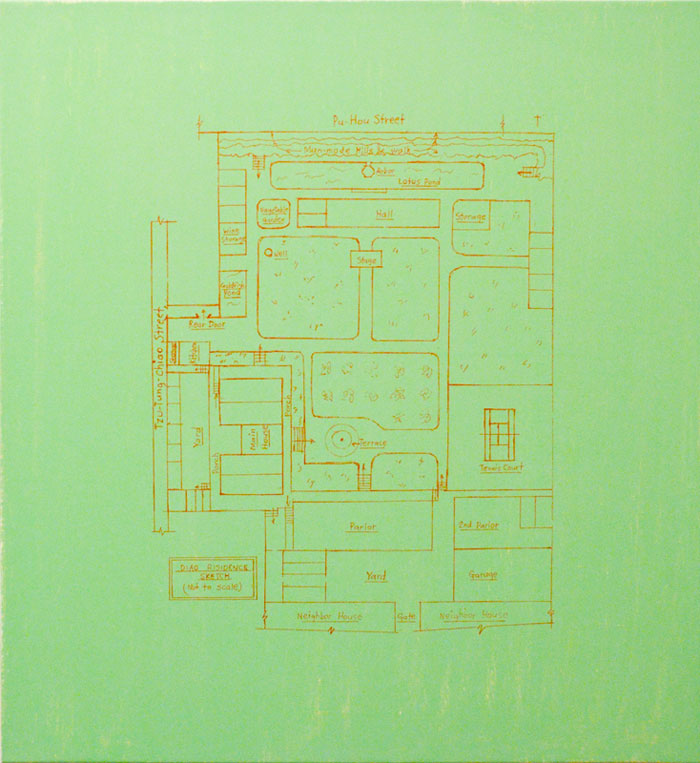

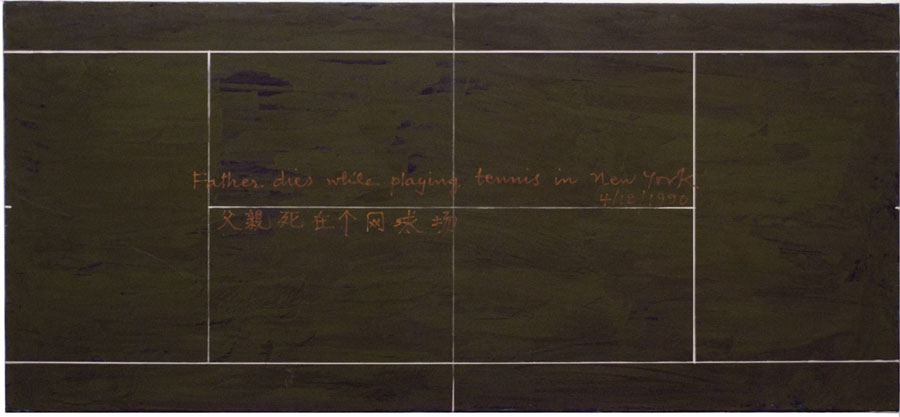

It’s a story that’s been in the back of my mind for 59 years—since I had to leave. As a kid I remember the place, but the scale was always weird. As a child every thing would always seem much larger. It hit me that one way I could pinpoint more the actual scale was to use the tennis court whose dimensions are standard. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

Besides the fact that there was a tennis court, what do you remember about the house from your time living there?

It was an unusual house in that it was not actually like a Chinese house. My western-loving grandfather had designed it with the help of a Canadian architect. It looked more Art Deco than pagoda-roofed. My memory is so fuzzy. All I’m really left with are the floor plans and the tennis court. I could not have done elevations and perspectives the justice they deserved.

So how did you go about recreating the home?

I’m working with the family lore, bits and pieces of narrative and stories told by my elders—the ongoing sense of loss that my elders felt. The house represented not only where they lived, but also their whole bourgeois lifestyle that was cut off. One of the things I did was to have various uncles and aunts describe their version of the house, their memories of the house, thinking that the older ones would have clearer memories of the layout and the scale.

And what did your relatives say about the house when you asked them?

So much about doing this project was cajoling these people to go back to their earlier life. The hardest person to actually get to go back there was the person who had the most possibility of imaging the house because he’s an architect. He’s my youngest uncle, 12 years older than me, so he lost all this when he was 18. He was the most intransigent—a young son, completely spoiled by indulgent parents, and his life changed drastically.

What’s happened to the house since your family left?

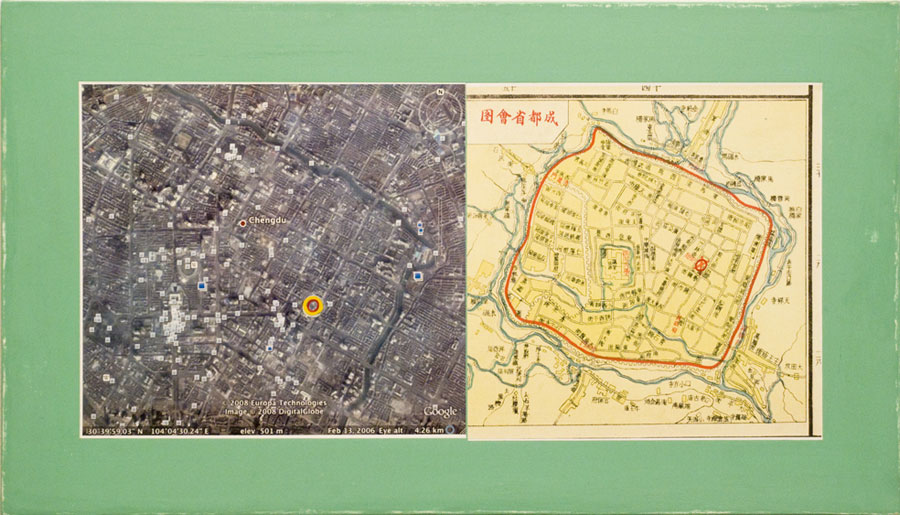

In 1979, I went back filled with expectation and horror, seeing my mother and brother (who were left behind) for the first time in 30 years. My brother took me to where the house was and it was a rubble-filled construction site. None of the standing structures had any relationship to the old buildings. Recently as I was working on this show I could see from the Google map that where the gardens had been there was still a garden. When the government first took over the house, China was emerging from the Civil War and they were very poor; they needed more office space for the Sichuan Daily, the Party organ that moved in. I know from my brother, who never left, that they built something immediately right on the tennis court, so as not to have to excavate or level the ground.

Did learning about family members’ versions of the house affect your memory and feelings about it?

The part of the reception of the show that’s strange to me is that people seem to focus on the emotionality of it. In making the work, I wanted to get the colors and design right. I didn’t want it to come off as a self-aggrandizement, or something arch and overblown. I wanted it to be graph-like and bulletin-board-like.

So the sentimentality is something that other people bring to this story?

It’s a surprise to me how people are reading this into the show. One of the things I can think of is everyone has had to leave a first home. No one can go back. I could say glibly and rhetorically that I’ve been working towards the show my whole life, but I’m glad I’m doing it now. If I had done it two years ago, fewer people would know where Sichuan is. But now more people are familiar with Sichuan because of the earthquake. And China is emerging as a world power. If I had done it 25 or 30 years ago, it wouldn’t have meant nearly as much.

Well, for American audiences, loss of home right now is a huge concern.

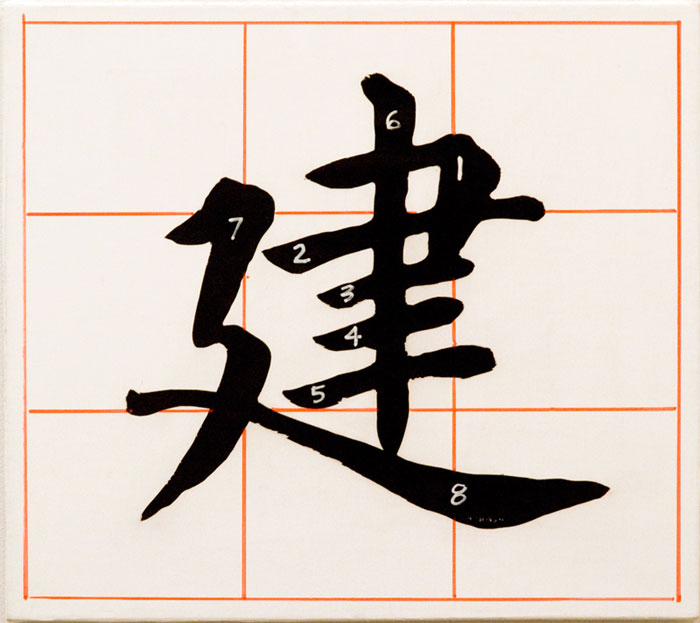

With Katrina and people losing their homes from the sub-prime mortgage crisis—it’s not a problem that’s going to go away. At some point I saw the larger implications of my very private story. That’s why I highlight the two characters: “To Construct” and “To Demolish.” I was led to highlight “demolish” because you see this emblazoned on a lot of buildings in China. [Painting] the character “To Construct” allowed me to reference the pedagogy of character writing which, after being numbered in such a sequence, shows you how to construct the character.

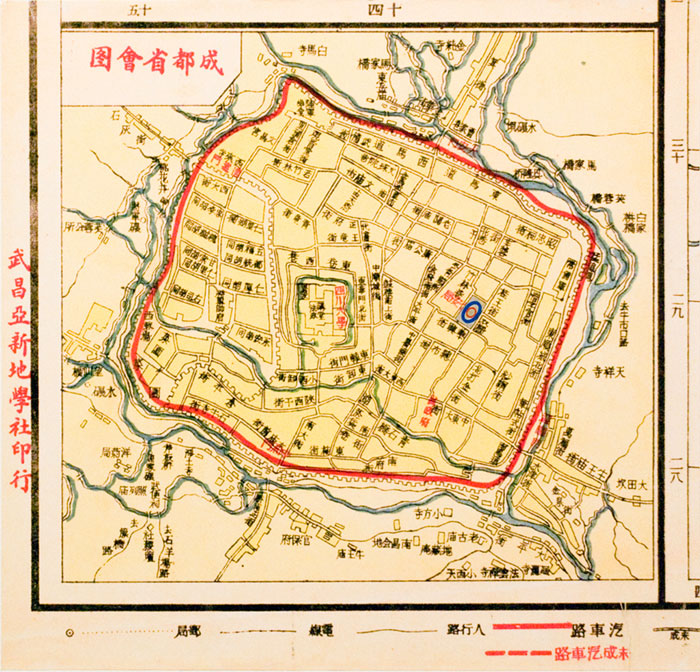

And why include so many scales and depictions of maps?

I love maps. One important influence for me is the writer/ designer Edward Tufte who writes books on how to depict information. I have worked a lot with diagrams and maps and numbers and columns of information, a lot of it on my part was a way of not being highfalutin. By using factual and archival information I get to circumvent the appeals to the spiritual and universal of abstract painting.

You mentioned showing this work in China recently. What was the reaction?

Sadly, almost none. I think it’s too common a story there. That’s what happened to millions of people, not just the loss of the house but also the ripping of the fabric of the family. Perhaps it was so traumatic it’s paved over by the unconscious. Also, China with its unbridled triumphalism and the Olympics then about to open, was probably not open to hearing anything negative about its past.

So how did the show’s presentation and reception differ in New York City?

In a way it was very important for me to make the show even clearer when I showed it in New York. It was important for me to set the locale for New Yorkers, even changing the title of the show. When I showed the work in China it was called the “Da Hen Li House” but for New York I thought that would seem too exotic. So I just decided to call it, “I lived there until I was 6…” Also, I didn’t need to show a map of China when I was showing the paintings in Beijing.

Showing the paintings in New York City, were you bringing two ideas of home together?

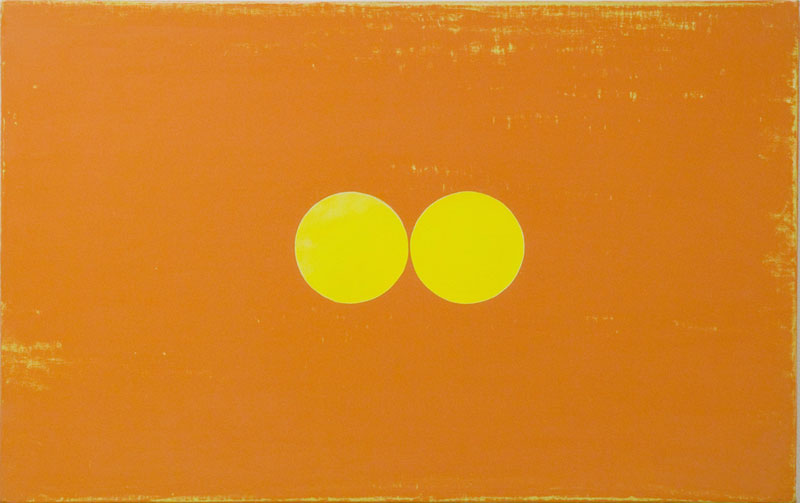

Foremost, I see myself as a New York-based artist. My references are very much to the culture of New York, both present and recent past. I’ve participated in the myth of “The New York School”, both as its descendent and also as a viewer of its demise. In the show, the two tennis balls refer to Jasper Johns and the Ginkgo leaves to Ellsworth Kelly—that’s the kind of playpen I’ve been in for years. I like the reference to this common culture.

There’s certainly a sense of common culture, and a way that almost everyone could relate to your story, but the show still seems so personal.

What people sometimes say to me is that the whole show could almost be seen as a commemoration of my parents. I wasn’t thinking of it that way, they’re just part of the story, but the fact that my father died on a tennis court adds to the elegiac quality. My return to China after 30 years was so traumatic for me that I stopped painting for a number of years. One of the reasons, I think, is I wasn’t prepared to see my well-bred mother, who once had every luxury, living in the depths of poverty as she was when I visited. The lack of amenities—not just food, also books, and the possibility of education for my nieces and nephews—was really so demoralizing and depressing. I am still amazed at how my mother survived, she was all alone. When I did come back, I couldn’t do much work, it was like, “why am I involved in this bourgeois undertaking of making paintings?”