Love in the Kingdom of the Sick

When an artist receives a heart transplant, his drawings of the procedure acquire all the gravity of a fever dream—intensely realistic, with hallucinations of the dead.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

The Morning News: How autobiographical is this series?

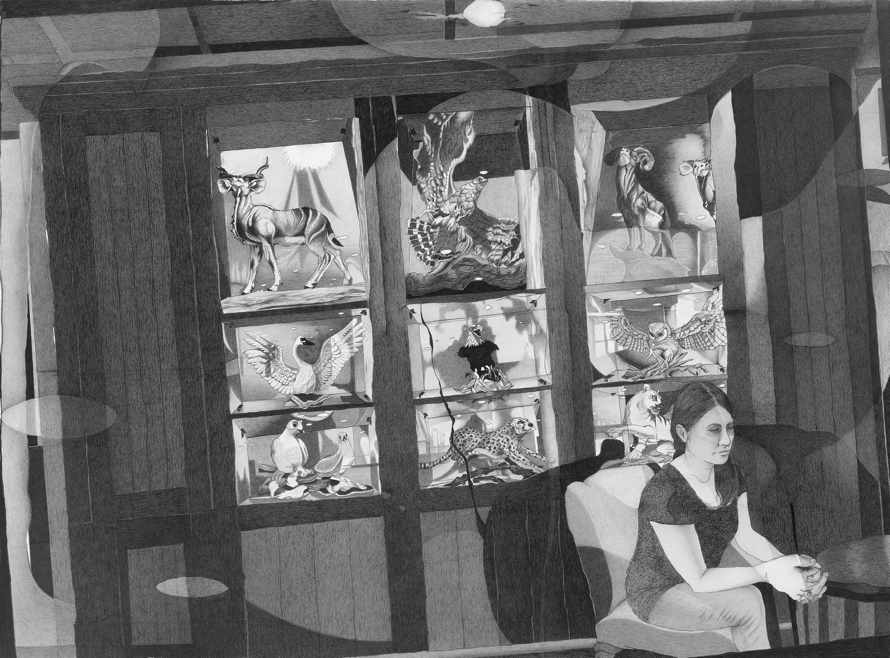

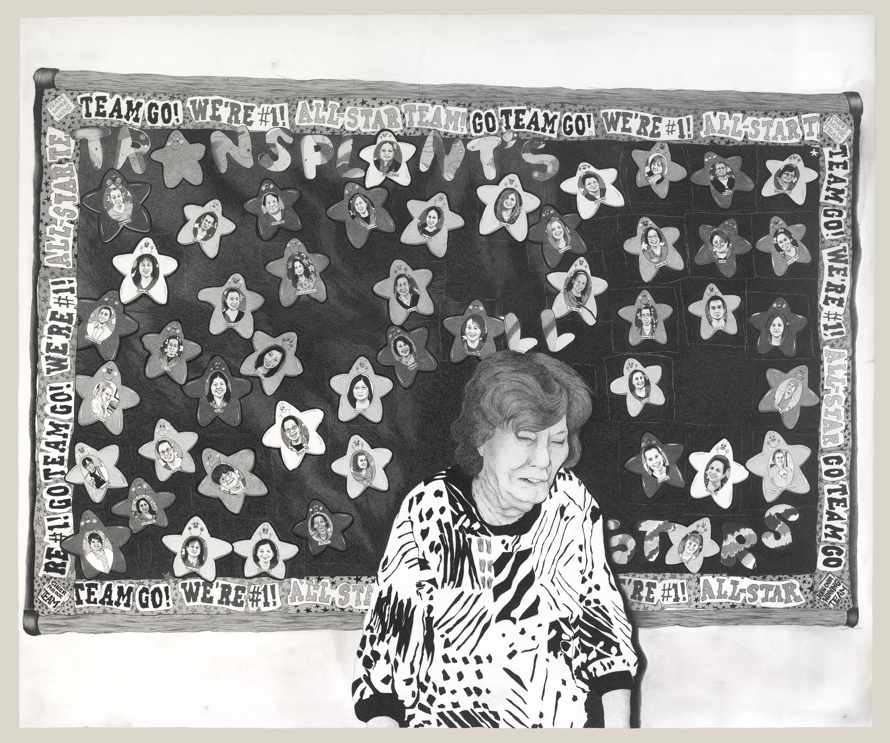

Michael Bise: All my work since my father’s death has been strictly autobiographical. This body of work is built around my experience of receiving a heart transplant in 2012. Having said that, the situations in these pictures are put together in a collage-like manner in which figures or objects appear together in a context in which they might never have existed. The old woman in “Stained Wall,” for example, is my great-grandmother who has been dead for many years. I used her to represent any number of figures you might see in a transplant center hallway experiencing extreme stress and emotion. She was laughing in the image on which I based her depiction, but because she had had a stroke, her happiness reads as grief. I found that poetic and perfect. Continue reading ↓

Michael Bise’s show “Love in the Kingdom of the Sick” is on view through Oct. 12, 2013, at Moody Gallery, Houston, Texas. All images used with permission, all rights reserved, copyright © the artist.

Interview continued

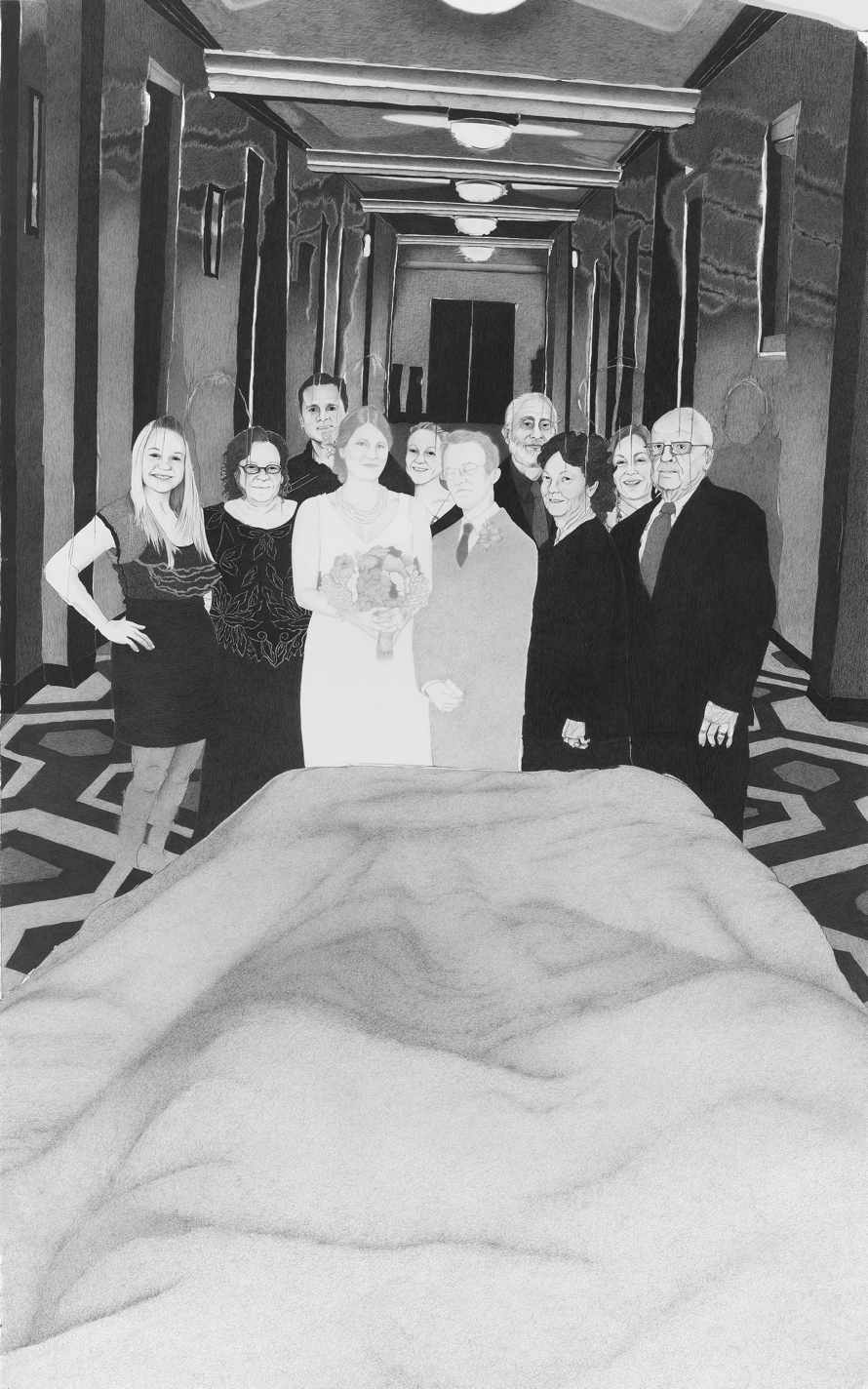

TMN: Talk about “Elevator at the End of Hall.” I find it terrifying.

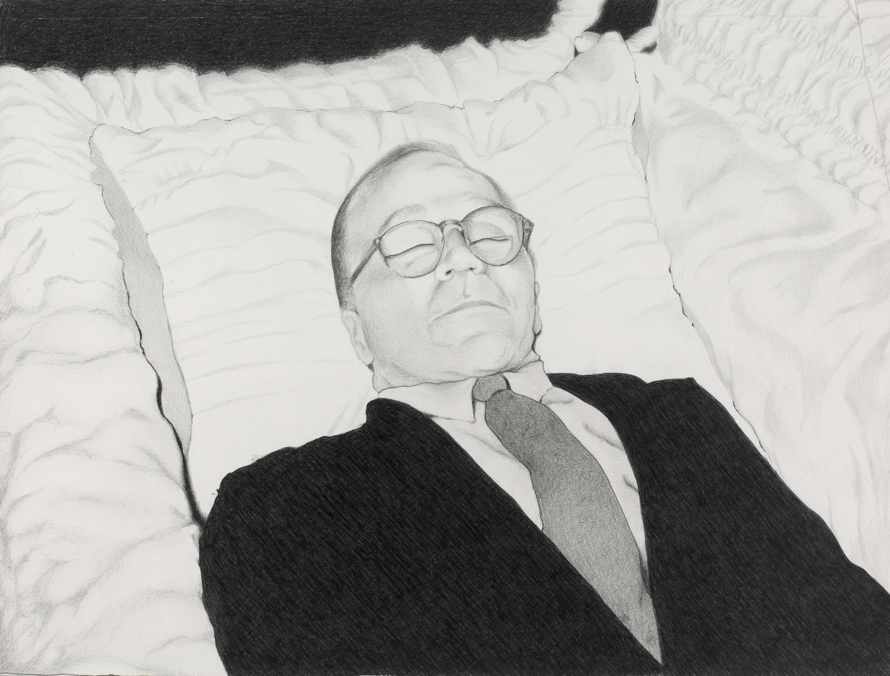

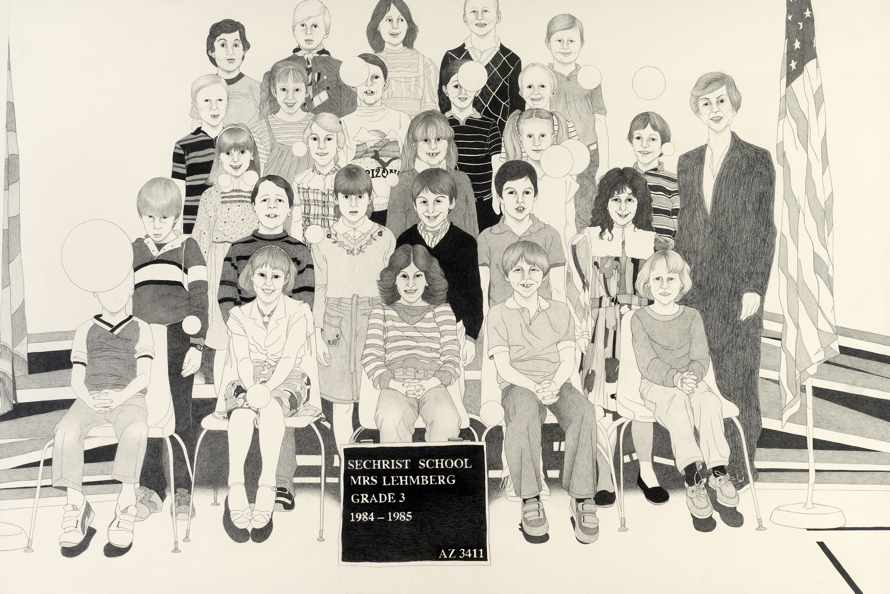

MB: The idea for that drawing began with the experience of sitting in a hospital gurney waiting to be wheeled into transplant surgery and saying what might well be final goodbyes to family members and friends. I decided to base the figures of my family on a moment during my wedding (after my transplant). In this way the drawing becomes a way to combine two different times, realities, and possible life outcomes. The faintly drawn figure in the suit is myself and I changed his face to reflect the face of my dead father in his coffin in the drawing “Dead Man.” It is meant to represent, as much as I can, the terror of existing in a life-and-death moment, hoping for a future and being entirely uncertain if that future will play out. The carpet/tile is also based on the carpet in the hotel in Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining. That’s about ghosts—but that’s a different question.

TMN: Do drawings connect you to people, or increase the distance from them?

MB: Experiences in the world connect me to people. The process of drawing them can be distancing as my depictions are invariably my idea of who they are. It can and does sometimes cause conflict when those depicted do not or do not want to see themselves in the image I’ve made.

TMN: What does drawing have in common with healing?

MB: Healing is a long, difficult, sometimes boring, sometimes exhilarating process that seemingly never ends. Making my drawings is very much like that. The most significant difference would be that healing is harder in the beginning of the process while making a drawing is hardest at the end.

TMN: You also write art criticism. Is the mind assessing your own work the same that assesses others’?

MB: Not really. I work blindly with little preparation, allowing the work to unfold in directions I could never predict. When I write criticism I have, at the very least, a fairly concrete idea of what I want to say. Most of the time, anyway.

TMN: Name another artist whose work has recently confused you or made you uncomfortable.

MB: An artist here in Houston named Carrie Schneider created an installation work called “Care House” in which she inserted works she had made (videos and sculptures) into the half-empty home of her mother who had recently died of cancer. The house contained physical evidence of her mother’s struggle through cancer (medicine bottles, calendars, doctor’s notes and prescriptions). A home movie of Carrie and her family at Christmas played on one of those old televisions we all remember. Viewers had to contact her and were given the gate code and a key and were allowed to wander the house alone listening to the ghosts, feeling the presence of death, and witnessing Carrie’s artistic reaction to it all. It was one of the most unnerving and powerful experiences I have had with a work of art.

TMN: Favorite pen for non-art?

MB: Uni-ball Vision. Fine tip. Black ink. Great design, available in any grocery store. I once bought an expensive pen and it continues to gather dust.

TMN: Marilyn Monroe reportedly said, “What’s the good of drawing in the next breath if all you do is let it out and draw in another?”

MB: Well, I’ve been in a situation where just doing that was a massive, fucking victory.