How did you first come to know Mark Mothersbaugh? As a curator, where did your interest in his art begin?

Adam Lerner:I knew DEVO from growing up with the music but I wasn’t into music enough to have known the name Mark Mothersbaugh. I am a little embarrassed to admit that I learned Mothersbaugh’s name as late as 2011 when I was researching an exhibition of an artist who photographed him. Since that exhibition coincided with a DEVO performance in Denver, I arranged to interview Mothersbaugh about his work with this other artist. Of course, within a few minutes of meeting Mothersbaugh, I realized he was one of the most interesting people I had ever met. Then, when I learned more about his art, I knew that I had to tell his story and introduce his art to the museum field and contemporary art world.

TMN:You suggest in the introduction of the book that DEVO has long been misunderstood. How should we understand it?

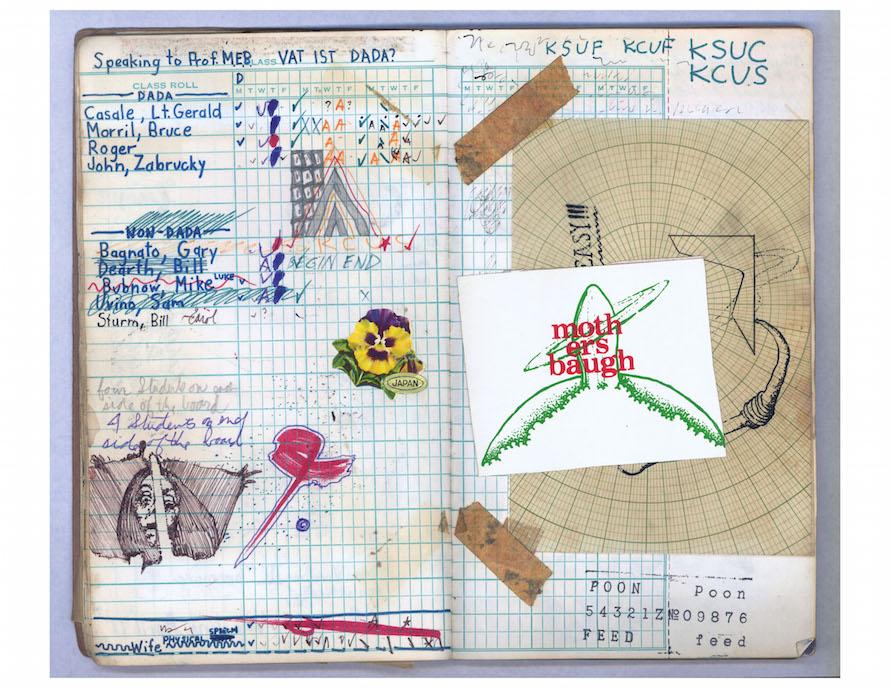

AL:Most people who know them think of DEVO as simply a band, and many of those people just know them as a quirky band that wore matching outfits and funny red hats. But DEVO was formed by a group of artists who wanted to invent a totally new format for making art: something that mixed music with film, art, costume design, even literature and philosophy (the idea of de-evolution) to some extent. That’s why they made all those crazy short films. That was their ideal format. Of course, most of the complexity was lost when those films ended up on MTV in the category of “music videos” and DEVO became just another band.

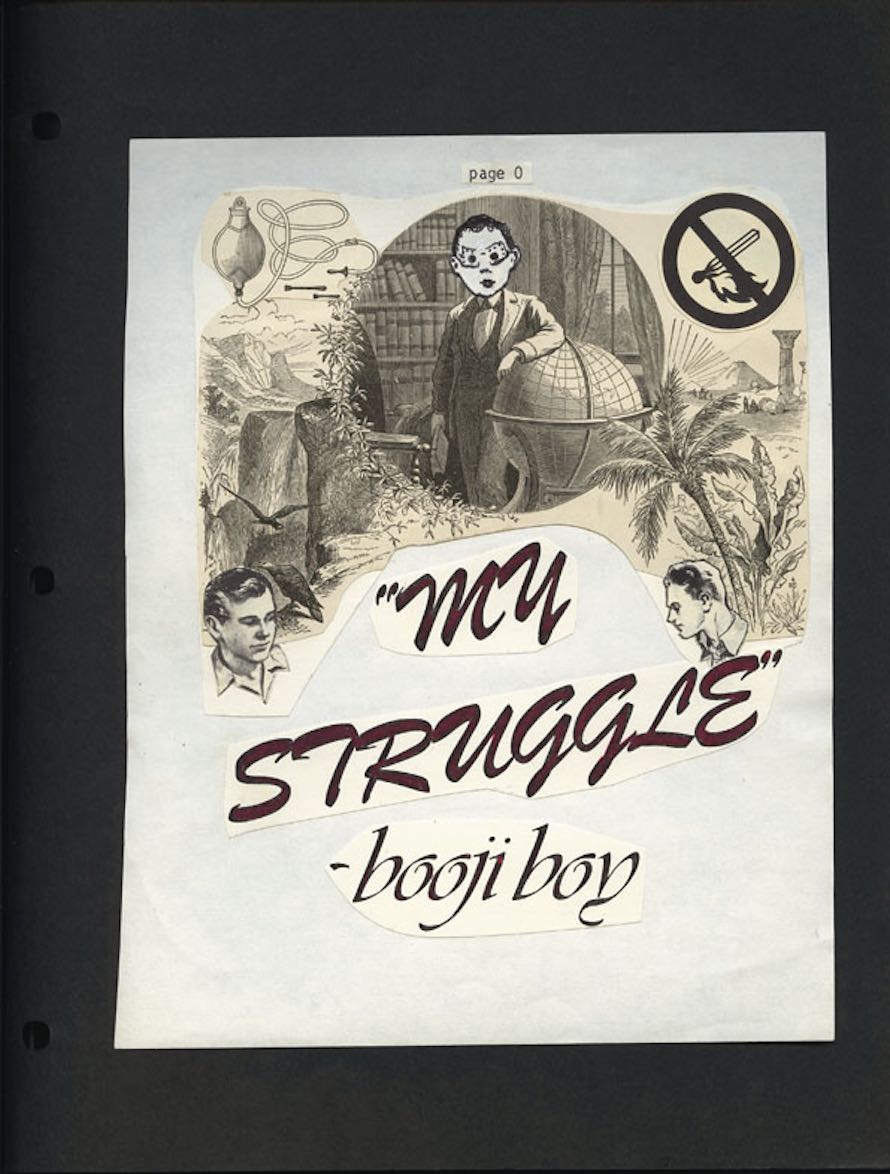

TMN:In the work, there’s a great sense of pain, or difficulty, in dealing with the world. Does this come from Mark directly?

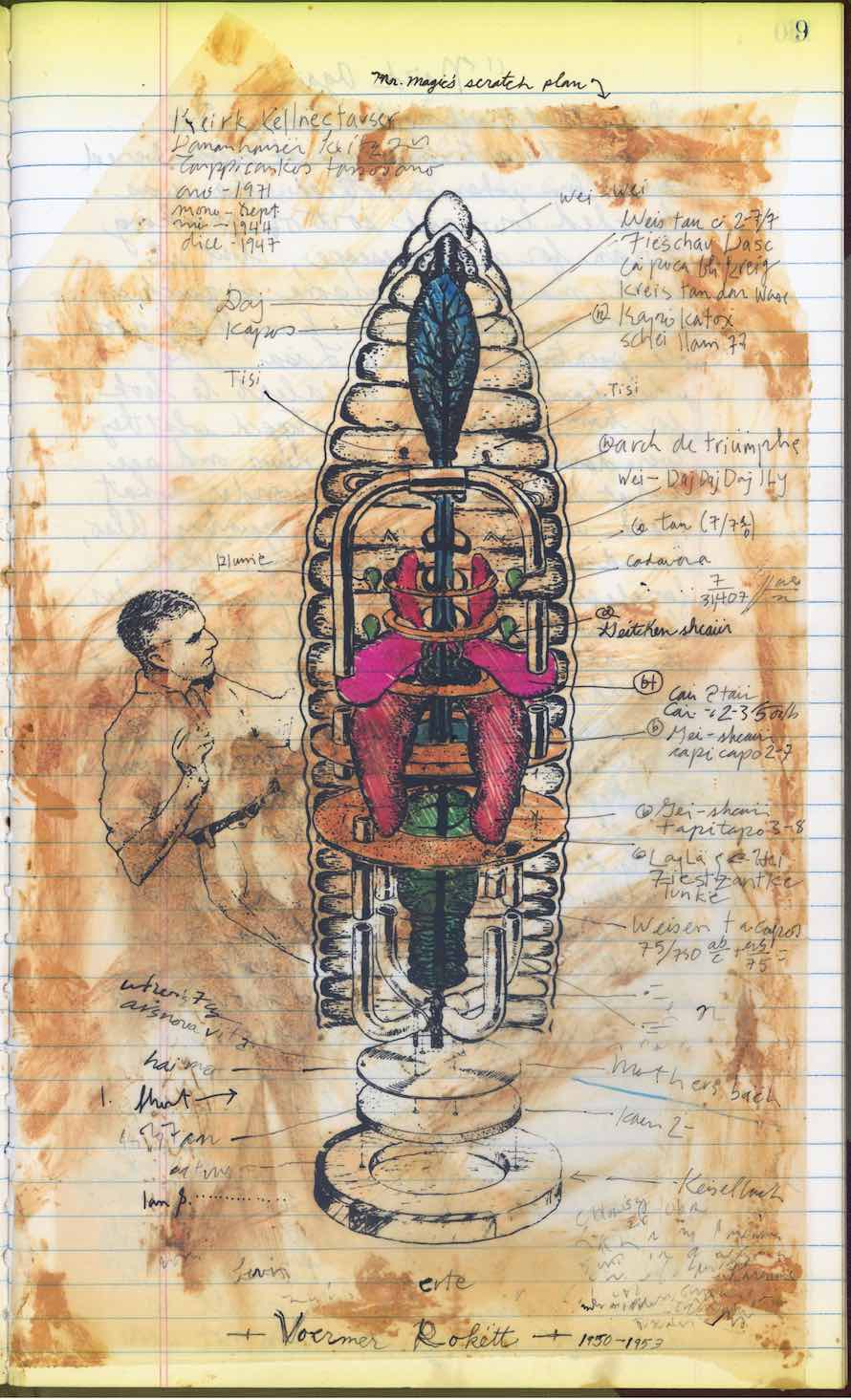

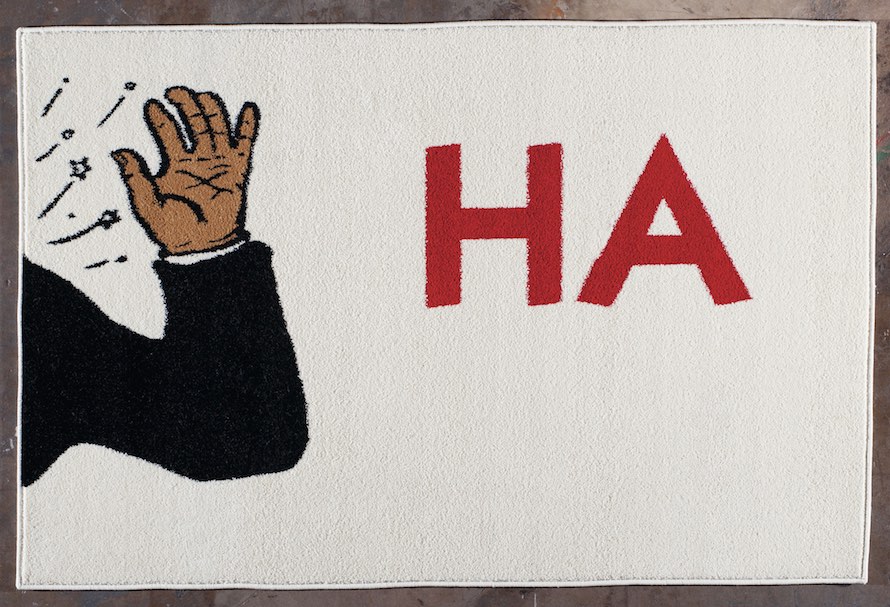

AL:All of Mark’s work celebrates outsiders, offbeat individuals, people who for one reason or another are not winning the game of life. I believe that comes originally from Mark’s very deep sense of himself as a mutant, someone who didn’t fit in with the rest of society. The fact that he was legally blind until he was almost eight years old probably has something to do with this sense of himself as an outsider. His ideas of the world as place of pain and struggle were reinforced when he was a college student at Kent State at the time when the National Guard opened fire on student protesters, killing four of them.

But there’s an optimistic streak that runs throughout all of his work as well, as if he were saying: In a world that is deeply afflicted, your only hope for regaining your humanity is to celebrate the mutant that you are.

TMN:Plus, there’s sort of a deep love for both the high-tech and the fuddy-duddy. Both in DEVO’s music and Mothersbaugh’s art projects. How important is technology?

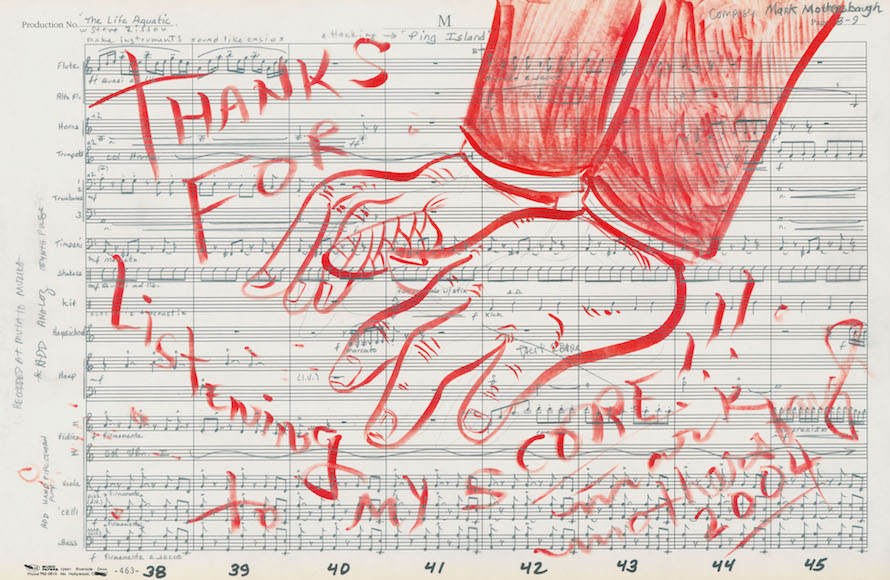

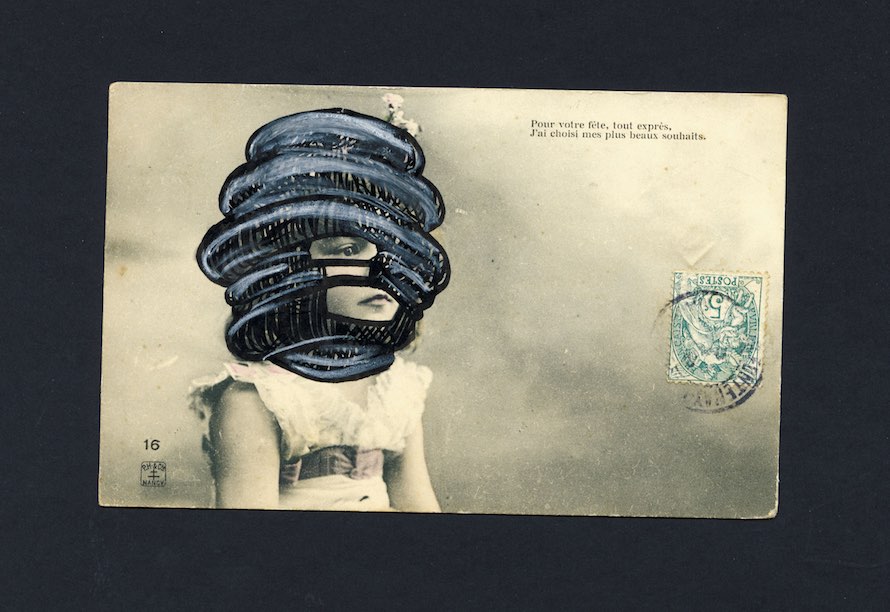

AL:Technology is Mothersbaugh’s frenemy. Even before DEVO, you can find images of mad scientists in his journals. Then, DEVO used everything from synthesizers to electronic drums. But they often manipulated new technologies to disable the tendency for machines to make everything sound the same. Mark sometimes performed on stage with DEVO using a calculator re-vamped into a synthesizer. He loves mutant instruments. That’s why he likes outdated technologies: They have a strangeness to them that allows him to create new, unfamiliar sounds.

TMN:As a museum director, where do you place Mothersbaugh in the fun-house of contemporary art?

AL:One of the great things about working with Mothersbaugh is that he has not yet been validated by the world of contemporary art. He’s presented his art in hundreds of small galleries, but, until now, he has not yet been the subject of a museum survey. Curators, critics, and art historians have largely not known what to do with him.

Right now, the field of contemporary art is open to accepting people it had previously ignored. So, Mothersbaugh is in the strange position of being something like an emerging artist with four decades of art under his belt. He is a predecessor to graffiti and “Beautiful Loser” artists like Shepard Fairey and Barry McGee, but he is having his art museum coming-out after them.

TMN:How do you personally see the art now that you’ve completed the book?

AL:Before producing the book and exhibition about Mothersbaugh, I was worried about how the contemporary art world would react to him because he doesn’t follow many of the protocols of the field. But now I feel like his career shows us the limitations and blind-spots of the art world. I realize that many of the most accomplished artists in the field have had only one major innovation in their career and they spend most of their lives building on that innovation. Mothersbaugh never cared about being accepted within the contemporary art field, so he was free to continually re-invent himself and work in new styles.

His effervescent production of an incredibly diverse body of work made me see that, while art museums and the contemporary art world are so concerned about talent, they often lose sight of what must be the very essence of art, that is, creativity. Mothersbaugh is never-ending fountain of creativity. That’s where his genius lies, not in any one object, but in the accumulation of things that he does and makes.