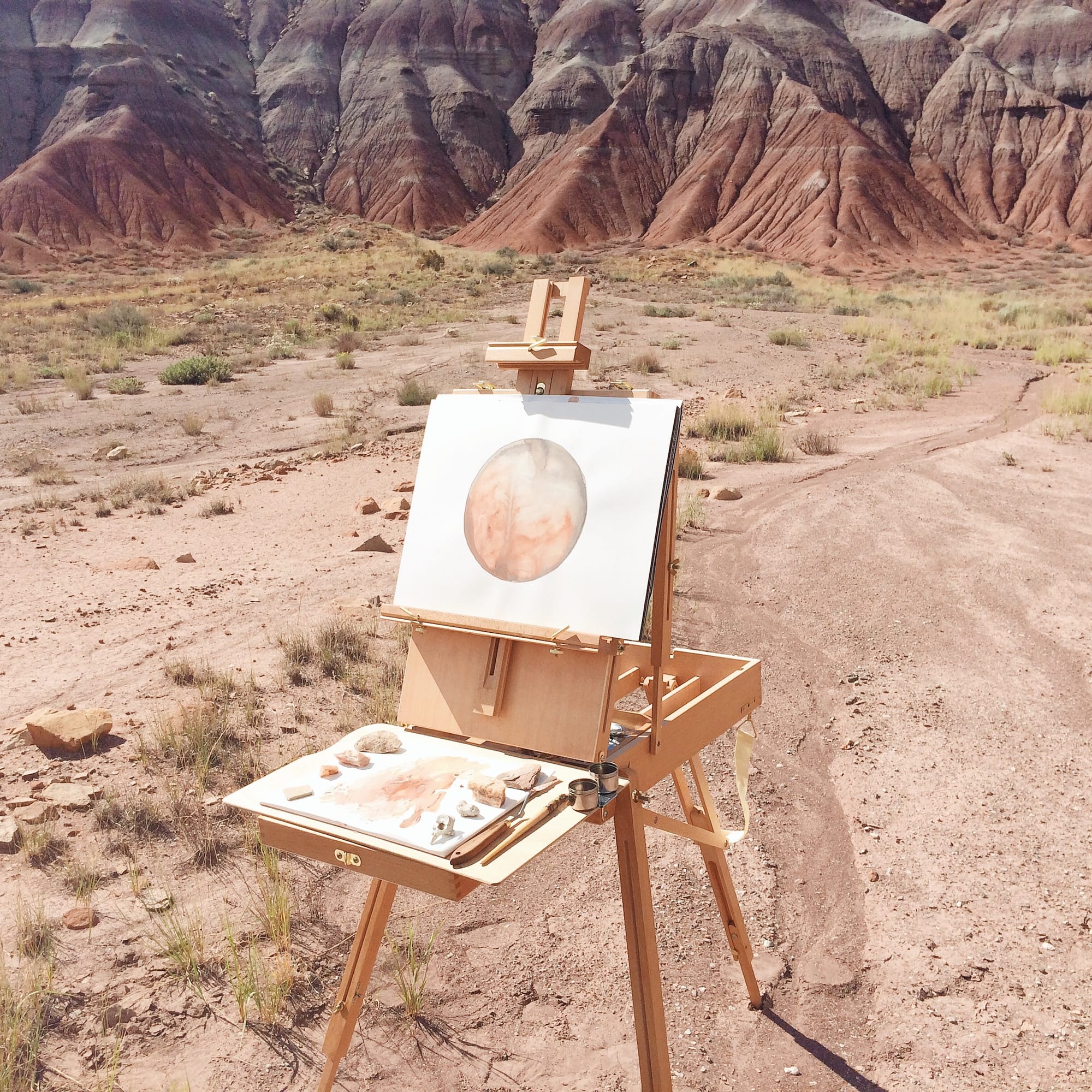

Mars on Mars

Stella Maria Baer has made a life for herself in the Northeast. But her ethereal treatment of the cosmos and the desert have won her a massive, devoted following.

Interview by Melissa Batchelor Warnke

The Morning News: Until a year or two ago, your work was heavily focused on animals, mostly odd pairs, from badgers and narwhals to anthropomorphic foxes and hedgehogs. Now you quite literally paint the universe—the cosmos and its moons—and photograph the desert. What’s the connection between the cosmos and the desert?

Stella Maria Baer: During the years when I was painting animals, I was often “distracted” by things that happened by accident while I was painting—the colors bleeding into one another, the movement of paint in the water. But I’d force myself to focus on painting animals. I spent most of 2012 moving from one commissioned animal painting to the next, most of them portraits of people’s spirit animals, and by the end of that time I burned out. I lost track of my own vision of what I wanted to make. I decided to stop taking commissions and to explore the things I had dismissed as distractions—the moments in my painting that felt out of control and more like play than anything else. For a while I made abstract color studies. Then I saw a photograph of a lunar eclipse and I decided to make a painting of the moon. In the sphere I found a balance of limitation and freedom, a way I could experiment with color and bleeds within a space that felt both infinite and finite. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission. Copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

Around the same time I was thinking a lot about where I grew up in northern New Mexico. When I was in high school I couldn’t wait to leave Santa Fe, and for many years I didn’t go back other than to visit my family. But around a year and a half ago that changed. I drove down to White Sands in southern New Mexico and for the first time I fell in love with where I was from. Then I took a road trip with a friend through the Mojave Desert and Arizona. When I got back to Connecticut I was haunted by the canyons, the colors, the lines. Painting moons and planets was a way to bleed out my memory of the desert while still moving into another place. There was a mythology of the desert that overlapped with the cosmology of space.

TMN: What do you listen to when you make art?

SMB: When I started the moons I was listening to Lord Huron’s Lonesome Dreams and Tycho’s Awake over and over. Lately I’ve been listening to the Modern Art Notes podcast—they did an interview with Sheila Hicks that I’ve listened to a couple times. I also talk to my friend Elisa Berry Fonseca, a sculptor, while I paint. We’ve been talking while making work for many years now, and I tend to take greater risks in my paintings while I’m talking to her on the phone.

TMN: How did Divinity School influence your work? Were you ever planning to be a pastor?

SMB: I went to Divinity School to study reconciliation and peacemaking between Muslims, Christians, and Jews, and ended up focusing more on religion and the arts, and my own practice as a painter. I did spend several summers in Israel, Palestine, and Jordan, studying Arabic and working at a women’s arts organization for refugees. But I was never planning on being a pastor. In Divinity School I realized that that I could say something in paint that I couldn’t say with words. The idea of incarnation—that God became flesh, that something infinite can become finite and dwell in time and space—that idea haunts me and my work.

TMN: When did you decide to make a life as an artist?

SMB: I worked for artist Titus Kaphar as a studio and research assistant for four years, and at some point while I was working for him I realized I wanted to do what he was doing. The decision has crystallized and then fallen apart many times, but it keeps crystallizing. At my first show there was something about the way people were interacting with and experiencing my work that helped me know it was something I wanted to keep doing. It was a secret I couldn’t keep to myself.

TMN: What does it mean to be a painter from the Southwest living in the Northeast?

SMB: It means I spend a lot of time thinking about green chile! A lot of my work explores a place I know and am from but haven’t lived in for a long time. I think most people, when they move away from the place they grew up, tend to create a mythology about where they’re from, and see it in a way that is different from when they actually lived there. My work explores the mythology I’ve created in the absence of being in a place.

TMN: You have a massive Instagram following, 112,000 and counting. Do their comments influence your work?

SMB: Instagram is a strange little universe. People from all over the world own my work because they’ve found it on Instagram. I’ve met painters and other artists and appaloosa lovers through Instagram, and in some ways it’s become a medium I work in. But it’s also full of trolls and robots and people who say weird things. Someone commented under one of my photos recently that I should wear different colors. I’m ignoring that advice.

TMN: The warm, muted tones in much of your work convey a sense of serenity. Is serenity a resting state for you, or an aspirational one?

SMB: Oh God, no! I mean, no, serenity is not a state I find myself in often. I spend a lot of time making paintings, taking photographs, reworking paintings, editing photographs. It’s a lot of work. Sometimes pieces just sort of happen in a moment, but most of the time things take time. Paintings often don’t turn out how I want them to and I get mopey and have call Elisa or Titus and then force myself to keep going. There are flickers of serenity, and I do love what I do, but most of the time making work is wrestling.

TMN: Is there work you make that you keep private?

SMB: Yes—I make a lot of paintings and take a lot of photographs that stay in my studio, and that only my sheepdog sees. I think it’s important to have secret work.

TMN: As a writer, I imagine that one of the hardest parts of a visual artist’s job is selling or displaying her creations. Do you have a dream for their lives after they leave you?

SMB: I hope my work will have a life of its own. I hope my work will speak to something that can’t be spoken.