May the Road Rise to Meet You

The traveling salesman would seem to be an elusive, dying breed in America. In Sara Macel’s “May the Road Rise to Meet You,” she hits the road with her telephone-pole salesman of a father, rediscovering him in the process.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

The Morning News: How long has your father been a telephone-pole salesman?

Sara Macel: Forty-three years! Dad started working in the treated wood industry straight out of college. He grew up in Pittsburgh and went to Dayton University for business. I think he realized in college that he was charming and personable, so sales seemed like a good fit. In 1970, he was hired right out of school by Koppers, which is based in Pittsburgh. He worked for them for almost 35 years and was relocated a few times as his sales territory expanded. By the end of his time with Koppers, his territory was basically the entire middle of the country. He’s been based out of Houston for my entire life and lives there still today with my mom. Continue reading ↓

Sara Macel’s first monograph, May the Road Rise to Meet You, was published by Daylight Books in 2013, and a traveling exhibition of that work was recently shown at the Center for Photography in Woodstock, the Houston Center for Photography. It is opening at the Silver Eye Center for Photography in Pittsburgh on April 3, 2015. All images used with permission, copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

When the economy took a downturn in 2005, Koppers let him go. He wasn’t ready to retire and had spent literally his entire life with one company. I think that was a very difficult time for him. Eventually, he started working for his former competitors and found a second life in the industry before retiring at the end of 2013. That kind of company loyalty and sticking to a single career path seems so rare to my generation.

TMN: As a photographer, did you see similarities in your careers?

SM: I decided to be a photographer in high school and have both my BFA and MFA in photography and have worked in the photo world since college, so I guess, in my case, the apple doesn’t fall far in terms of sticking to one thing.

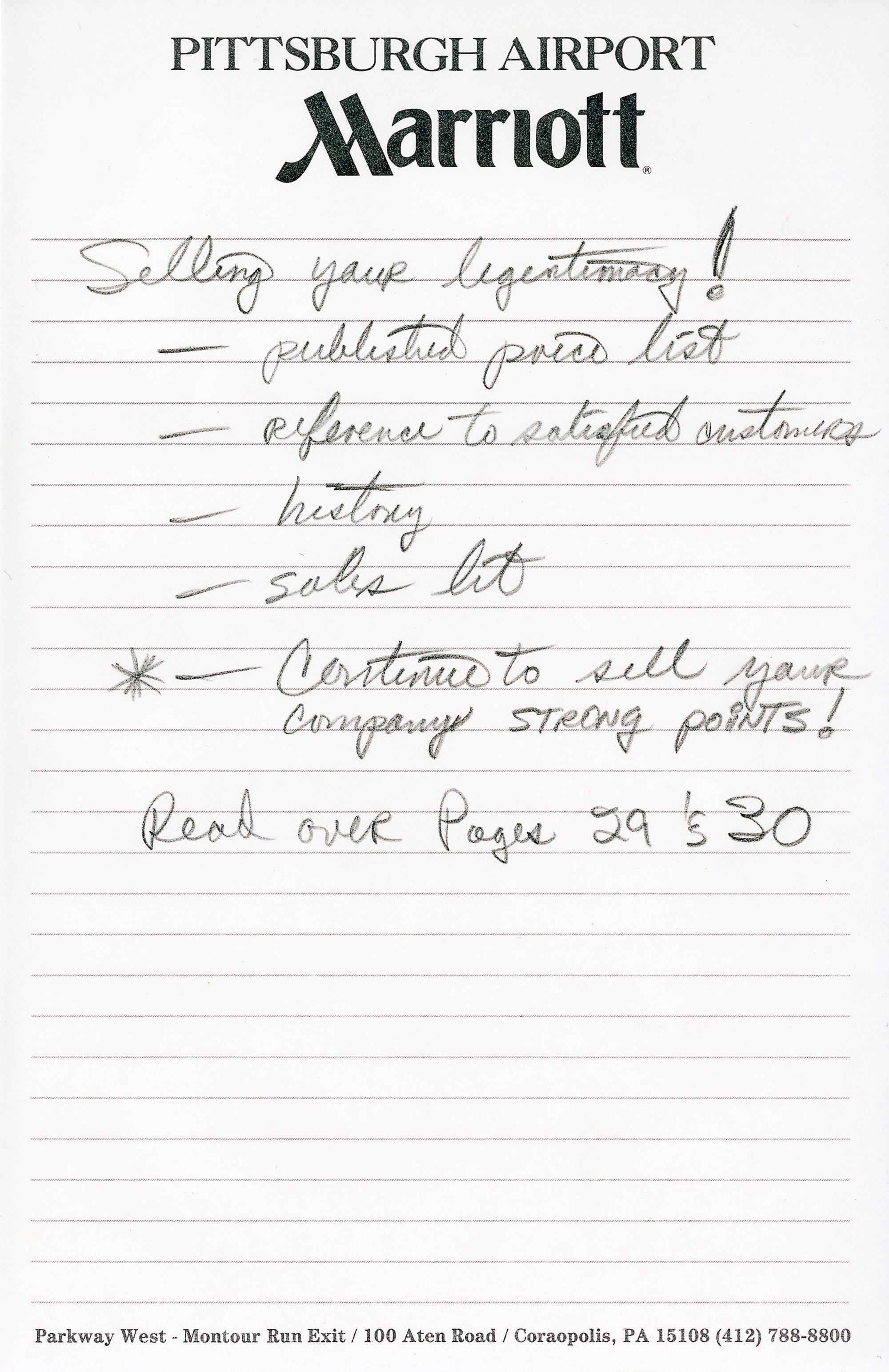

May the Road Rise to Meet You started as a conversation between he and I about our different experiences on the road in our respective careers. In the two years we spent working on this project, there were a lot of long car rides from one place to the next where I’d basically interview him about his life on the road. I have to say, I think we were both surprised by just how similar the life of a telephone pole salesman is to that of a freelance photographer. I’m often selling myself and my work to collectors, curators, editors, etc. We both are well rehearsed on our elevator pitches. And we love talking to people and getting them to let their guard down a bit. For my dad, it’s about making that connection to lead to a sale, but often for me it’s about getting a stranger to let me take their portrait. That said, we’re also both thick-skinned when it comes to rejection. It’s just part of the deal: you win some, you lose some. Also, Dad is no stranger to working the booths at sales conventions, which is very similar to the portfolio walks and reviews I do as a photographer. We both spend a lot of time traveling alone, eating alone, and staying in hotels. He’s still got me beat on all the travel rewards points, but I’m getting there.

TMN: How did your father respond to being a subject?

SM: Well, he loves to joke with his old co-workers and customers that he retired as a salesman to start his new career as a model.

Initially, I was very concerned about him opening up to me. He always kept his work life very separate. After spending so many years building relationships with clients and traveling solo, I knew it would be a struggle to get him to let me in to that part of his life. And it was. He was always supportive, but I think he was more interested in pretending for the camera when it was just us than letting me shadow him in real-life. That issue of control is certainly one we deal with in our father/daughter relationship as well, so it wasn’t a surprise to see it pop up in our subject/photographer roles either. As an artist, I had to make that part of the story.

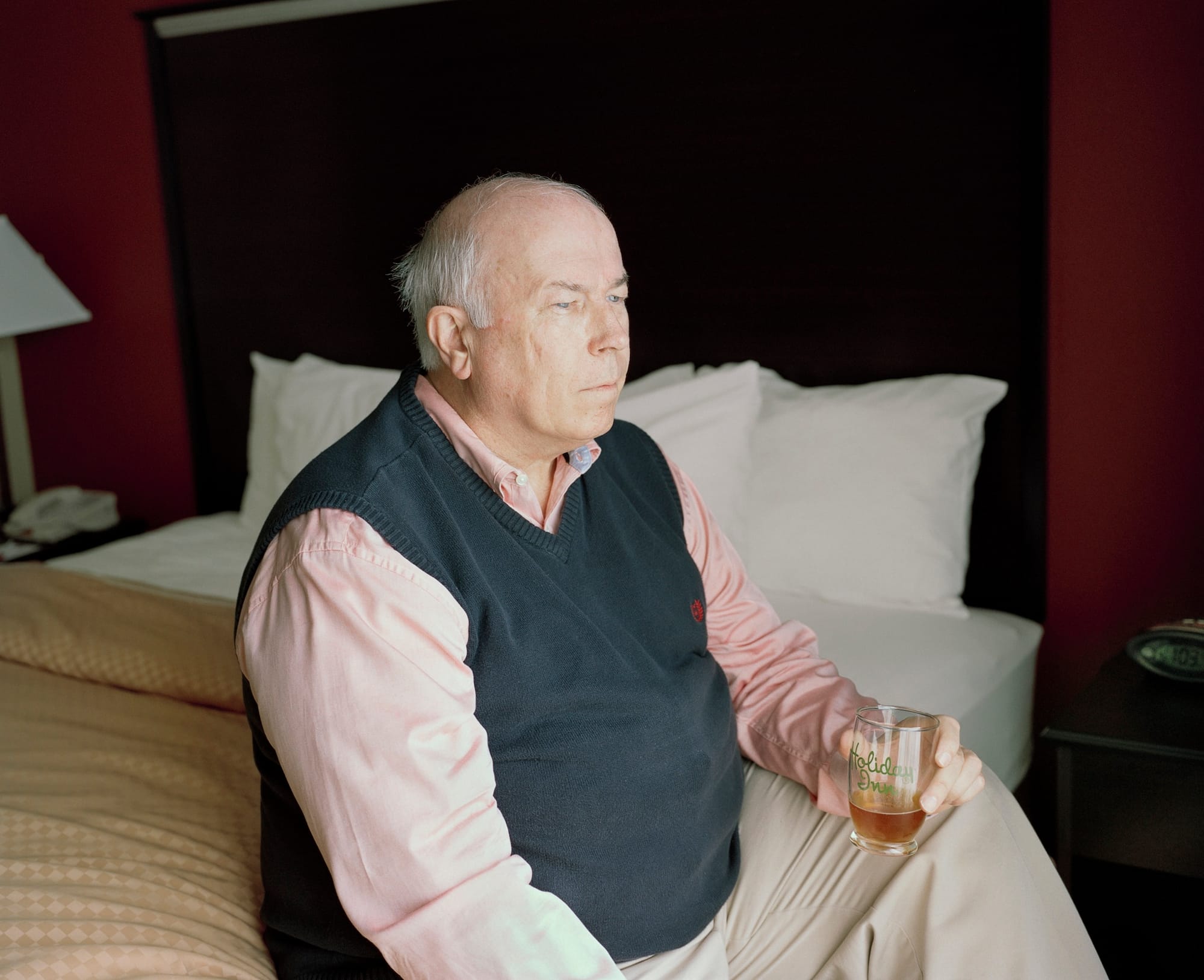

His initial reluctance to bring me on business trips with him led me to going through his files and finding places from his past to explore on my own. Those solo trips led me to photograph men who reminded me of my dad and places that looked like they still lived in the past. The book embodies this weird place where time is fluid—he is a young man at the beginning of the book (in the cover snapshot that my mom took the year I was born when he was the age I was when I began the project) and he’s an old man sitting on a hotel bed when the book ends. Over the course of 42 images, the viewer sees his entire career condensed into one long business trip. Some photographs are shot in a very straightforward documentary style, and other images are completely constructed performances that he and I planned out.

Honestly, the best thing he has said to me about the book is this: at the end of his very last day working, his boss called him to thank him for his years with the company. He hung up the phone and picked up my book and slowly went through it cover to cover, reflecting on his life. And then he quite literally closed that chapter and began a new one. He said it felt like being handed a trophy after a marathon. To be able to give him that gift means so much to me.

TMN: What is life like for the traveling salesman?

SM: It’s a lot of downtime. A lot of traveling to get from one place to the next. He’s never late for anything, so there’s a lot of getting up early and being near the meeting and killing time reading the paper. Then it’s a quick face-to-face, maybe meet another customer for dinner, then back on the plane and home by dinner the next day. He traveled to another city or state every week. Sometimes only for a night, sometimes he’d be gone all week. In the early days, he had an office in downtown Houston with a small staff, but as things were downsizing in the ’90s, it became a home office. On those days when he was working from home, we knew when the doors were closed, we had to be quiet. He’s always on the phone.

TMN: What surprised you about your father during the trip?

SM: Well, first of all, the whole project was shot in different chunks of time. Sometimes I’d come home for two weeks, sometimes less. In between trips, we’d talk about the photographs on the phone. He’d call me when he had ideas for things we hadn’t shot yet, like the photo of him surveying. He found that hard hat in the back of his closet and called me really excited about it. He said, “Oh, I found this great hard hat we gotta use in a shot!” And when I came home, he pulled it out with a lot of old maps that marked where the poles that belonged to his company were located in our area. We drove around so he could check up on them and so I could make that photograph. It was fun for me to see him get more comfortable with the camera. He’s not a patient man, so his patience with me and my direction was a nice surprise.

Probably the other most surprising thing to me is how much he’s learned about my working life. Being a pretty corporate kind of guy, he never really understood what the life of a photographer looked like. This whole process of making the book and now having gallery shows and artist talks has brought us so much closer. He comes to a lot of the events related to the book and completely steals the show.

TMN: Was he ever uncomfortable with the process?

SM: Introducing the camera into our relationship was difficult for both of us at first. It was hard for me to direct him and even harder for him to act natural when we were shooting. This was the first time I’d photographed the same person over and over for a long period of time. A lot of the early photographs I took of him aren’t in the book. Now I see that they were just exercises to get us both to a place where we could be comfortable in this new photographer/subject dynamic.

He was also very reluctant to let me photograph meetings with clients. It wasn’t until a year into working on this with him that I met anyone he worked with. But, honestly, I never set out to shoot a documentary about telephone-pole salesmen. From the beginning, I was much more interested in “the road” and seeing the landscape through the eyes of a road-weary business traveler. This American idea of “the road” is well-worn territory in the history of photography, from Walker Evans’s work for the FSA to Robert Frank’s “The Americans,” through works by Joel Sternfeld, Stephen Shore, and Alec Soth. All of them men, all artists, all looking to say something about this land and its people. My dad traveled down those same roads and is one of those people just sitting in a diner waiting to meet a guy and sell him some utility poles. That’s what I wanted to photograph—those in-between moments. There’s a loneliness to that life that I relate to. As a woman who is often traveling alone and is very aware of how different it is to be a woman alone on the road versus a man, I was interested in seeing the world through his eyes.

TMN: As an artist, when are you lost?

SM: Whenever I’m starting a new project, I can feel lost. You have that initial rush of excitement to be shooting something new, but once I’m back in the studio editing new work doubt creeps in. But it helps to talk to other artists. I think most of us feel like frauds at times, but no one wants to admit it. As an artist, you experience ebbs and waves. The real trick is allowing yourself to ride them out, because then you realize it’s all part of the creative process.