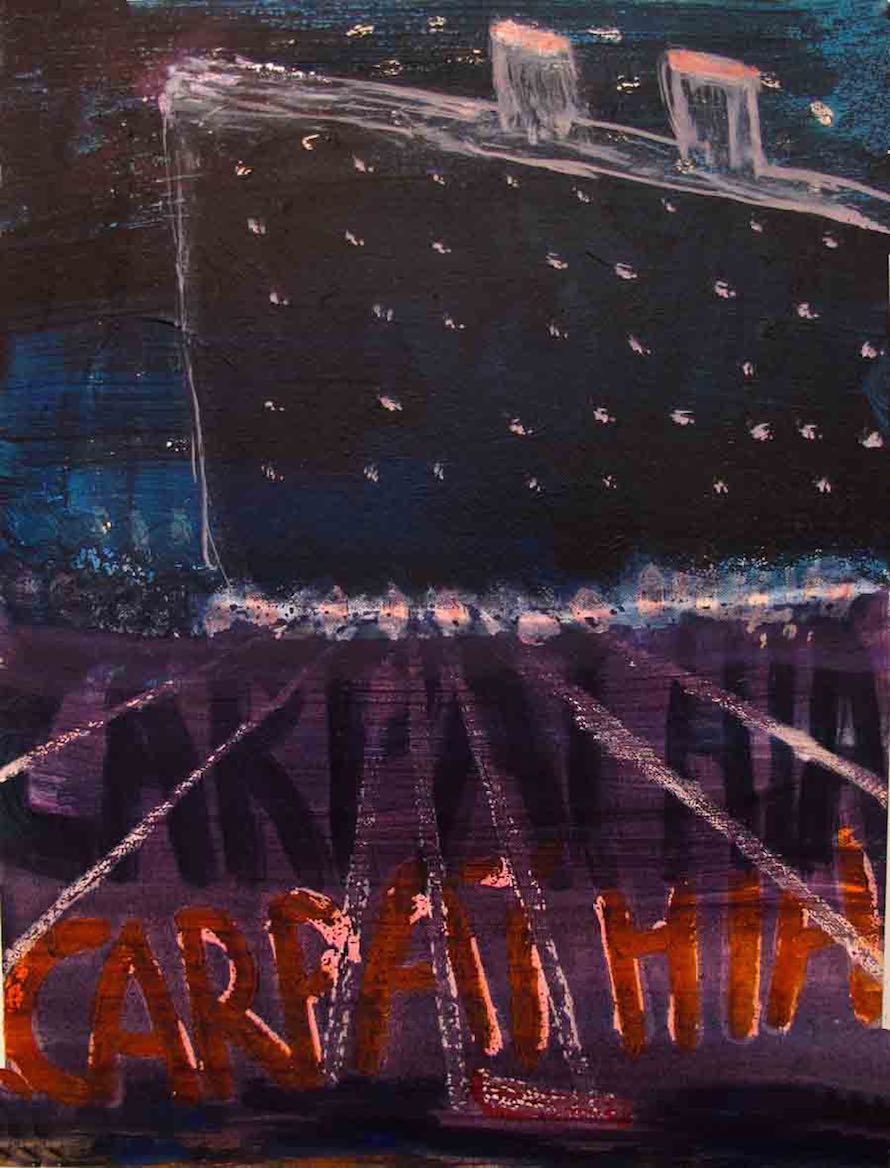

Night Divers

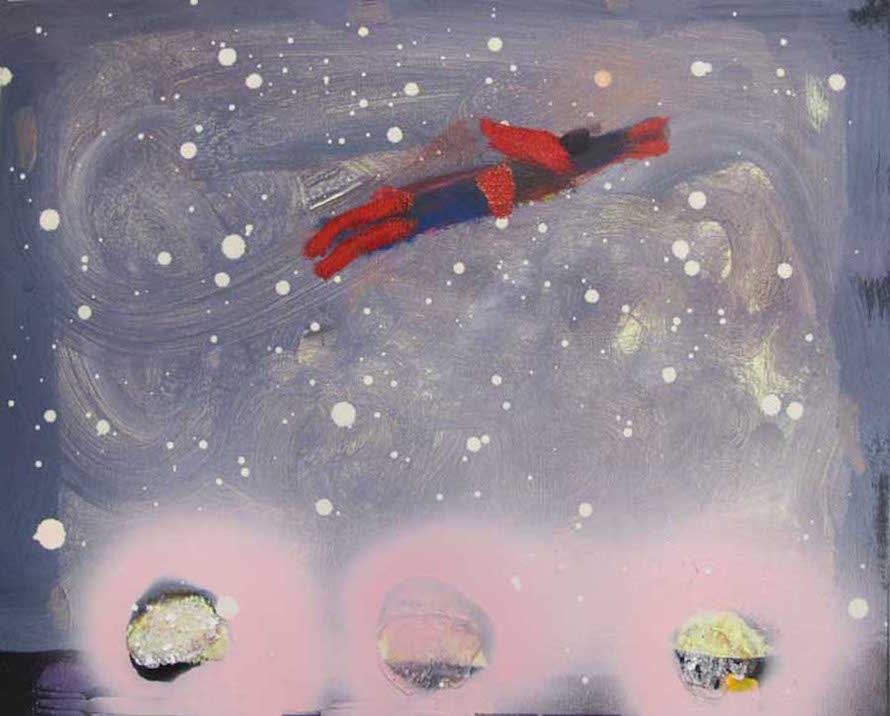

Paintings of divers, ships at sea, and Superman—wearing underpants or not—find common ground in quiet mystery.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

The Morning News: I see a lot of mysticism in your paintings. The pictures of ships, for example, especially Sargasso—there’s a sense of seeking something indirectly. When you’re working on a painting, when does its purpose appear—from the get-go, or somewhere in the process?

Katherine Bradford: My studio is filled with dozens of paintings, all in various states of completion. Sometimes it takes me years to finish a painting; I usually find the image in the process of layering on the paint.

When I started out I considered myself an abstract painter, a kind of mark maker. Occasionally letters of the alphabet would appear or shapes that looked like recognizable things. At first I painted these out, but then I gradually let them coexist with the marks until finally I came to terms with the fact that my paintings could exist as pictures as well as abstract fields, and I began to enjoy discovering stories which would unfold as the painting progressed. You’re right about a sense of mysticism and seeking. The story of a quest is one of my recurring themes. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

TMN: It’s certainly a long-running theme in literature and art. As a child, what were your first artistic leanings?

KB: One Christmas my parents gave me a set of puppets from a second-hand store that were handmade. They had wooden heads, cloth bodies, and came with a stage and draw curtains. Each puppet had a distinct head set in a weird expression. It was the first time something really strange came into my bourgeois childhood.

TMN: Figures and narrative seem important to your work, but they’re nebulous. Even the Superman paintings can be read a number of ways. When you begin a painting, do you work from a story that’s already set?

KB: I think of nebulous as describing a visual state, a kind of haziness or atmospheric quality that I actively seek. When I began to paint I was living on the coast of Maine where there is almost a daily dose of fog. I used to refer to this as “pearly gray light” and I loved it. Seeing indistinct shapes in the distance feels familiar to me and leaving a painting so it can be read in any number of ways taps into a mystery which is also a quality I want in my work. Nothing is really “set” as I tend to paint by reacting to what is already on the surface.

TMN: Where does your attraction to water begin?

KB: Using a wide brush, maybe three inches or so, I begin a painting by stroking on a color horizontally. This inevitably looks like water, like light hitting the surface of little rivulets. Willem de Kooning said oil paint was made to paint flesh, but my oil paint always ends up looking like an expanse of water or sometimes sky. You could say this comes from being surrounded by the ocean when I lived in Maine, and now in my studio in Brooklyn—I’m aware also of the East River glinting in the distance.

TMN: What’s the most beautiful object in your house?

KB: We have a crimson rug that was made in Morocco. I bought it from the painter Katherine Bernhardt and her husband Youssef Jdia, who run Magic Flying Carpets of the Berber Kingdom of Morocco. Whenever I walk across this rug I’m enveloped in a field of intense wine red, a color that both gives off light and is as deep as the ocean.

TMN: Whose work do you admire that you could never imagine your own being compared to?

KB: Rose Wylie, the British painter, makes work that is big, open, and has an unschooled charm. She just had an important show at the Tate Modern in London. We both got a late start, spent many years raising children, and are going full tilt in our 70s. But her work is more outrageous than mine, more unapologetic and eccentric. She uses line a lot where I use shape and color. We’re scheduled to be in a show together and I hope it comes off.

TMN: What was the first piece of art you ever sold? What was the experience like?

KB: The first time I pinned my work up on a wall and put a price on it someone bought it the next day. I found out he was an architect, which made me really happy since my family is full of architects (but not artists). The piece was humble, small, and cheap, and it gave me a lot of self-confidence that someone wanted to live with it.