Notes From the Rebuild

Nicole Pasulka and photographer Linda Jaquez visit the St. Bernard Project in New Orleans, and find a neighborhood once devastated by Katrina, now reinvigorated.

A white truck crawled up and down Upper Ninth Ward streets, dodging potholes and slowing occasionally to check out trim work or a particularly careful paint job. “These blocks are really coming back. Look at all the people out on the street today,” my companion said with a grin, a construction staffer at Habitat for Humanity.

As heartening as this enthusiasm is, it’s more the result of survivalist’s optimism than real-world objectivity. Anyone visiting New Orleans who manages to leave the French Quarter will be shocked to find neighborhoods where nearly every fourth home has been abandoned or demolished.

I came to New Orleans last September, just after the fourth anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. Since then, I have been researching volunteering—how and why people do it and the difference it makes in a town equally known for colorful paint jobs and relentless celebration as for blight and struggle. As part of my project I’ve been volunteering with various nonprofits both rebuilding housing in New Orleans and serving the homeless population. I have no clue how many volunteers pass through the city from elsewhere, but I’ve met hundreds of tourists, locals, and temporary transplants who are here to hang siding or serve hot lunches.

Despite the ubiquity of abandoned houses, I started to focus on construction, development, and rehabbed homes. I gradually stopped noticing shotguns with sagging foundations that threaten to break in half and Creole cottages with missing exterior walls. Even though I was doing research, talking about and working on houses in New Orleans every day, my awareness of the damage and its implications became passive. That is, until my friend photographer Linda Jaquez came to visit. As I drove her down Claiborne from Canal Street and over the Industrial Canal into the Lower Ninth Ward, she said little more than “Oh, my God.”

Here, ironically, I live in the cheapest, nicest apartment I’ve ever rented. Part of the reason I’d stopped noticing the damage in New Orleans was my own relative comfort, but it was also because as a volunteer I had been absorbed in rebuilding efforts.

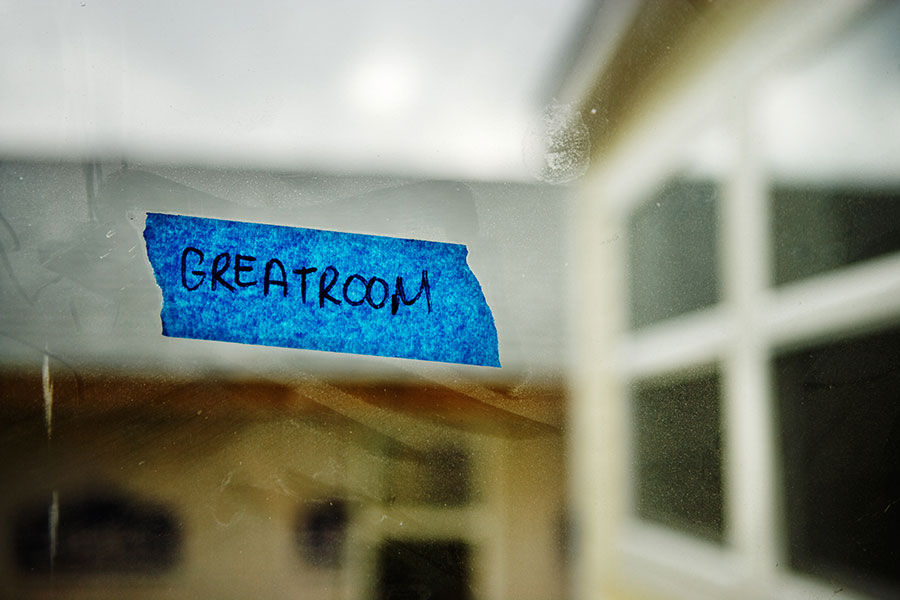

As everyone I’ve worked with understands, New Orleans is still in recovery. But recovery implies return. Because of this, Linda and I decided to focus our collaboration on rebuilding. Not the before and after, but the during. It’s our guess that people outside the city rarely get the opportunity to see the work that’s being done right now to turn flood-damaged houses into homes again—by Brad Pitt, sure, but more often by volunteers like you and me.

For those who can’t find the money or the time to rebuild themselves, the task often falls to nonprofits. No one knows how many homeowners are still displaced, but significant increases in housing costs have made it difficult to move back and restore homes. Relief funds were awarded based on property value rather than cost to rebuild—so grants were often insufficient for many homeowners living in neighborhoods where property values were low. Also, many rebuilding funds provided by the Louisiana State “Road Home” program were lost to thieving contractors who swarmed the city after the storm.

I’ve heard numerous nonprofit staffers explain that if you still need to rebuild four years later, there’s likely some serious impediment—displacement, illness, extreme financial misfortune, lost documents. In this messy, deficient environment, nonprofits have stepped up—uniting donors and volunteers eager to help rebuild New Orleans with homeowners unable to make ends meet.

It was cold and rainy the morning we tagged along with Justine Buzzell, one of three construction managers for the St. Bernard Project, as she made the rounds—checking on the houses she oversees that are currently being rebuilt. Originally from Massachusetts, Justine spent two years in AmeriCorps, one in the AmeriCorps National Civilian Community Corp (N.C.C.C., or “N-Trip”), which travels throughout a particular region doing various service projects, and another as an AmeriCorps director with the St. Bernard Project. After falling in love with New Orleans as an N-Trip, Justine told me she asked around about organizations to work with and found that “everyone who’d worked with the St. Bernard Project was obsessed with it.”

St. Bernard Parish, the area where the St. Bernard Project does most—but not all—of its work, is a working-class area southeast of New Orleans bordered by the Mississippi River to the south and Lake Borgne to the north. During Hurricane Katrina, a 25-foot storm surge destroyed the levees in St. Bernard, and after the flood the entire parish was declared uninhabitable. As of July 2008, St. Bernard parish has regained almost 50 percent of its pre-Katrina population. In March of 2006, Liz McCartney and Zack Rosenburg founded the St. Bernard Project and began gutting houses in the area. In 2008, Liz was CNN’s Person of the Year. (Word to any future nonprofit directors looking to gain huge volunteer turnout and funding for your organization: Become CNN’s Person of the Year.) The St. Bernard Project has rebuilt more than 250 homes since the storm, and when Justine took us around last December they had another 50 under construction.

The following day, Linda and I met with Cambria Martinelli, AmeriCorps Program Manager with Rebuilding Together. Unlike the St. Bernard Project, Rebuilding Together is a national organization that’s been working on home preservation in New Orleans for more than 20 years. Before the storm they helped elderly and disabled homeowners who weren’t able to keep up on basic repairs, but they’ve since shifted focus to rebuilding for low-income people who are elderly, disabled, or have young children, and whose homes were damaged by Katrina.

In close collaboration with neighborhood associations, Rebuilding Together often rebuilds numerous homes on a particular block—”for the sake of the ripple effect,” Cambria explained. “When you work on seven houses on one street, it’s an encouragement to the homeowners. We’ll often do an exterior paint job even before the house is finished. A lot of that is to send the encouragement, ‘Hey this person’s coming back.’”

On the day I volunteered with Rebuilding Together, we primed and painted the exterior of a beautiful old shotgun down the block from several abandoned houses.

Rebuilding Together’s houses are frequently heirlooms built by a homeowner’s own family members. “For our construction managers to walk into a house and have to think of everything that could possibly go wrong and every way they need to retrofit something takes a lot of ingenuity. You’re working on someone’s art.” At the St. Bernard Project, most of the houses they rebuild, though older than Katrina, are still relatively young buildings. When you get into Orleans Parish homes, though, you can easily find walls made from scrapped or sold off barge boards—19th-century wood taken from disassembled, flat-bottom boats from the North that weren’t going to make the costly trip back up the Mississippi.

By fixing moldy frames, crumbling floors, and rotting porches, volunteers and nonprofit staffers are not only building homes, they’re taking New Orleans recovery into their own hands. Last November I spent a week volunteering with the St. Bernard Project. On Friday, we were invited to a reception for a man named Randy MacCaughey, who, in an effort to raise money for the organization and awareness about Katrina rebuilding, had ridden his bike from Shreveport, La., to the St. Bernard Project offices in Chalmette. There was cake when he crossed the finish line, and once the applause had died down, Randy told the staff members, volunteers, and documentary film crew that had been following him, “ It’s just taking too long.”

He continued, “This is what we do in America when things take too long. We do it ourselves.”