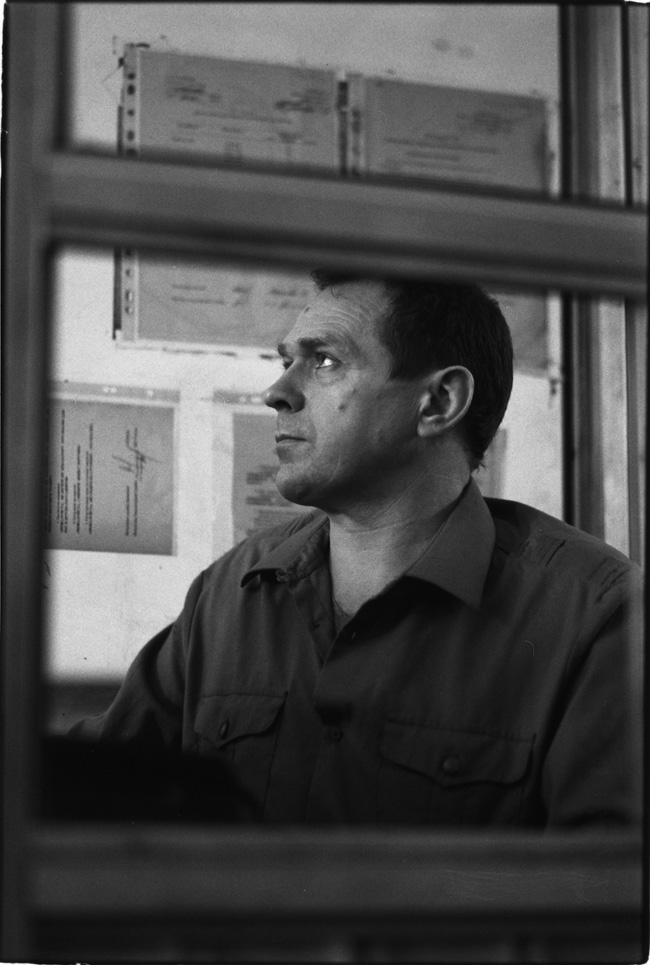

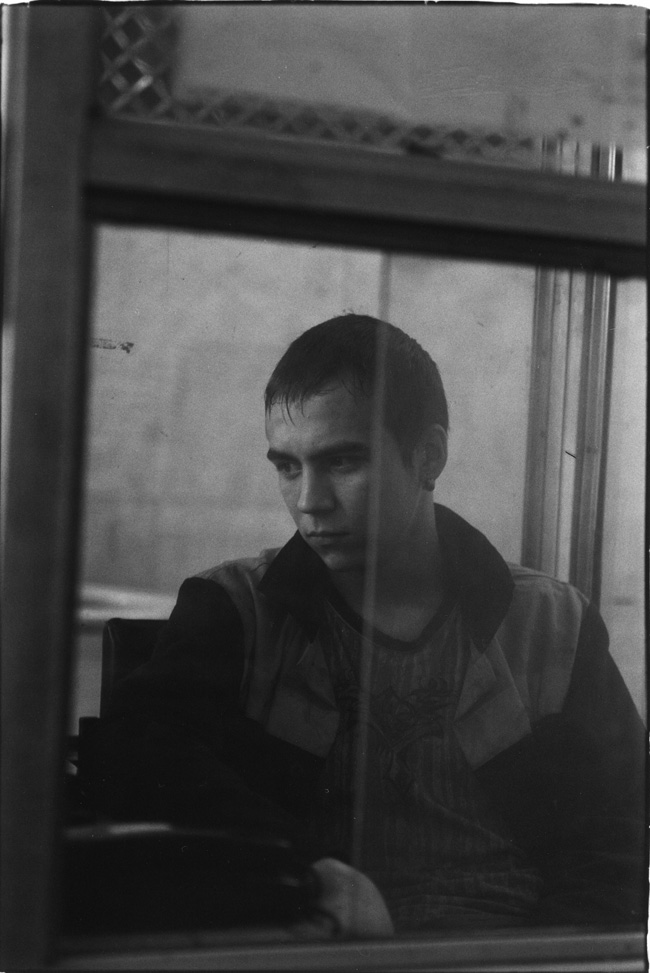

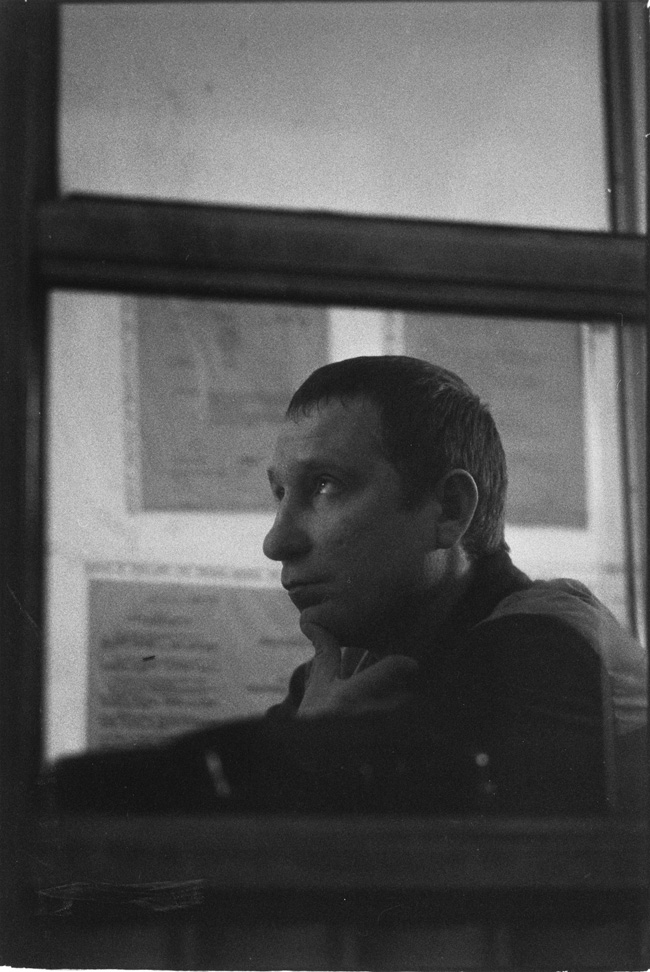

On Duty

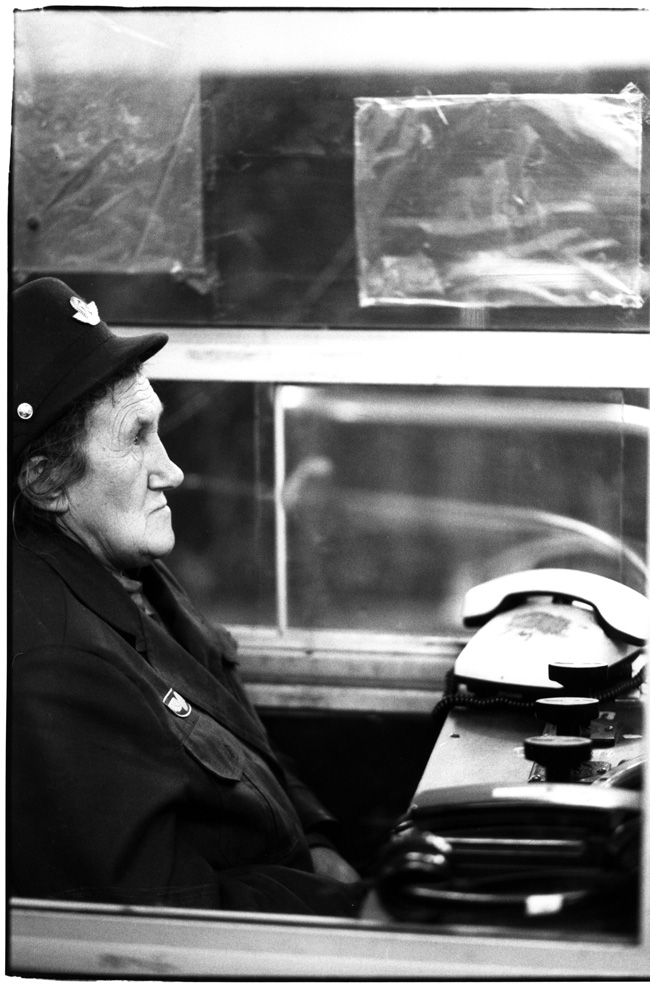

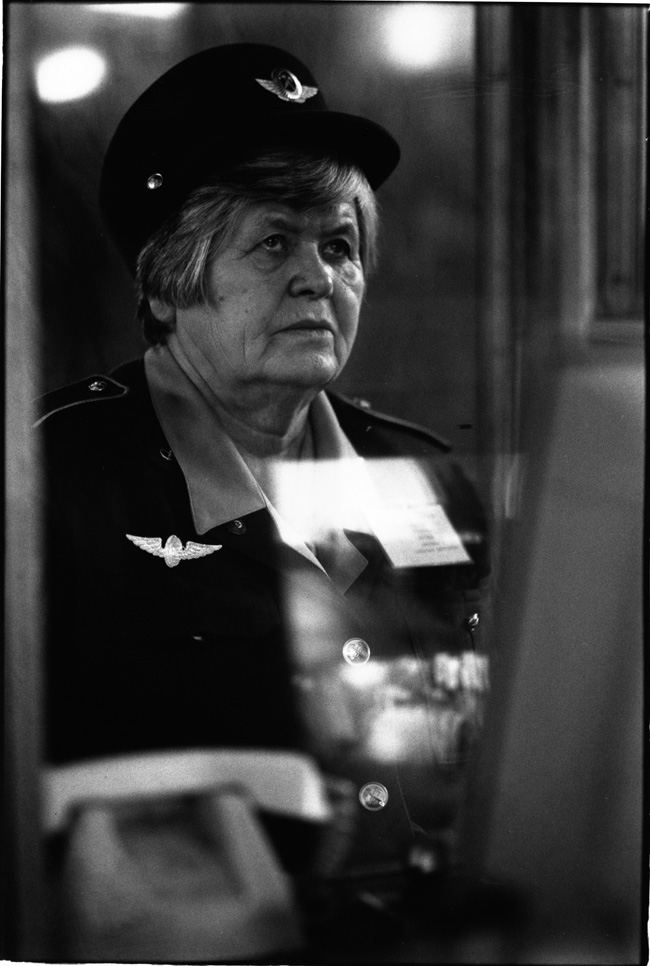

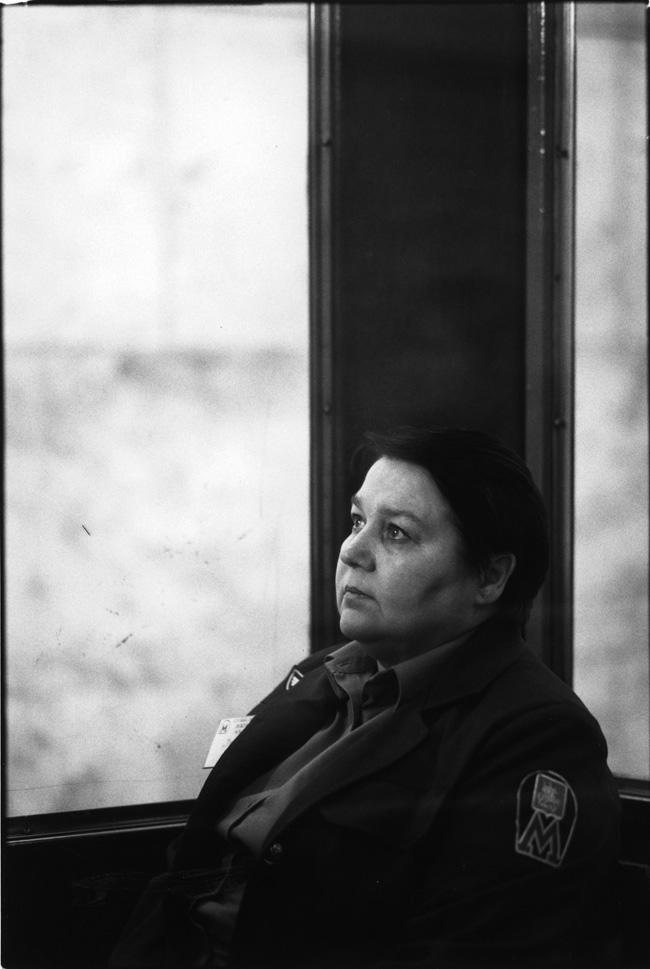

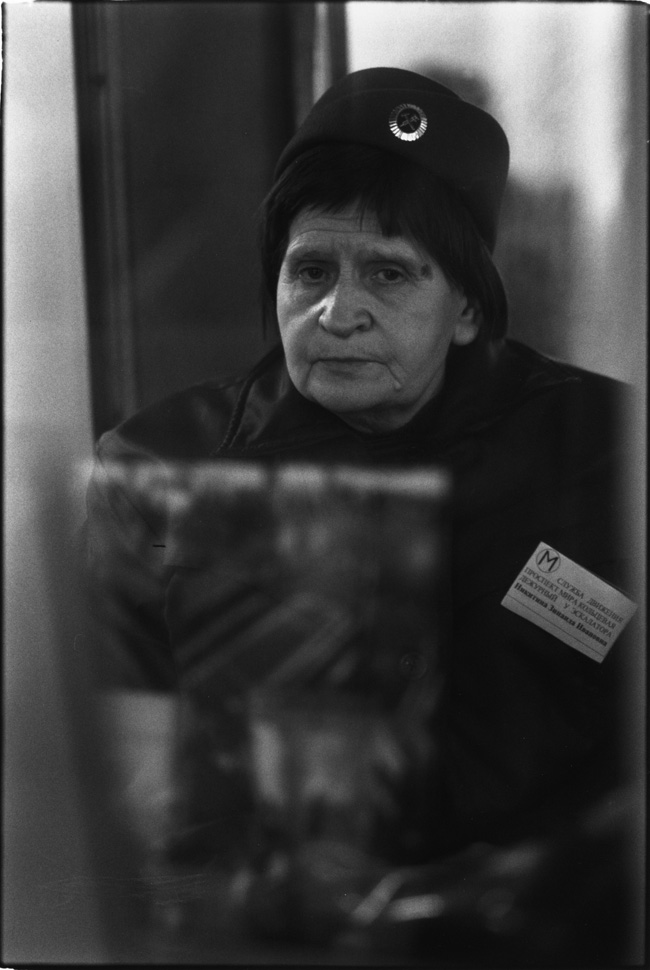

The Moscow Metro workers in Olga Chernysheva’s photographs are examples of people seen but not noticed. Despite this, the watching, waiting faces in her work demonstrate grace and openness.

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

I can’t help but be drawn in by the stillness of these watching faces. Who are these people on duty?

These are people who are always here. They’re always present. If you go to the Metro you may not see them. I feel like it’s important to be attentive and to watch the many things around me. At the same time, I feel that I should be relaxed. If I was always attentive then I couldn’t [come up with] a concept and I couldn’t react. Continue reading ↓

All images courtesy the Artist and Foxy Production, New York. All images copyright © Olga Chernysheva, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

In a way, you’re like your subjects when you’re making art, present and also somewhere else.

When I’m working, I react to situations which are asking me and awakening me. Here, there was something very familiar. I think that [the subjects of the photographs] represent the perfect condition for the artist. [They are] taking care of people and they are both “on” and “off” at the same time. When I was photographing them I was especially moved by their eyes. This gaze is sometimes looking outside and sometimes looking inside. I tried to make these very classical photographs. The Metro doesn’t have the proper light and it doesn’t have good conditions to make these kinds of portraits, but for me the gaze of these people was very traditional and very classical.

How is it that the moments you’ve captured are familiar but also seem very unique?

I like to find a beauty that is not supposed to be there. [The work explores] how life is constructed based on the beauty and the miracle. It’s an operation of our vision and attention to find it.

Did you pose these pictures or did you just stumble upon your subjects?

I found [the subjects] and I spent quite a long time watching them and wondering if I could take their photographs. You’re not allowed to take photographs in the metro. I was going to use a tripod and get special permission, so I made this a project. There’s a magazine in Moscow and the owner is a friend of mine. I asked him if we could do the project together because I always concentrate on people from the town—how they’re living, what they’re doing. He said yes, and we published the photographs in a magazine with a little interview.

What kind of interview?

We asked the people: Do you like your job? What do you do? One lady said, “I feel very important because so many people pass me. I feel like the general at a parade.”

What a wonderful and unexpected response. How do people end up with these jobs?

Often they are women over 50 who are retired. This is a job after their careers are over.

Why did you shoot in black and white?

If you take color photographs directly in the Metro, you get this greenish light. In the light itself the color in photographs is not that good. I wanted to make classical photographs in a nonclassical space. I really wanted to make traditional photographs. I even had them specially printed out because I wanted to use silver [gelatin] paper. In Moscow now, it’s not possible to print like this because people have really jumped to digital.

Have you shown this work in Moscow?

Yes. They were in the Moscow Biennial, which just ended.

How was the reception?

Good. I didn’t expect it because, for me, this is very far from contemporary art now. When I was thinking about the aesthetic [of this work] I was thinking about themes of Tarkovsky. He was living in Soviet times and he was ambivalent; he was not as Soviet as Eisenstein. But he [worked] in the ‘70s, and in the ‘70s the Soviet system was already very weak. He made a lot of very beautiful films and he has a very serious attitude towards the human being. I was thinking about the aesthetic of the ‘70s [when I made these photographs]. When I sent these photographs to the curator of the biennial I said, “Don’t you think it’s old-fashioned, because I was thinking about the ‘70s?” She said, “Oh, the ‘70s is very fashionable now.”

How is your work connected to Moscow and its residents?

For me it’s about opening a new corner or new atmosphere in Moscow; what is open already but hidden.