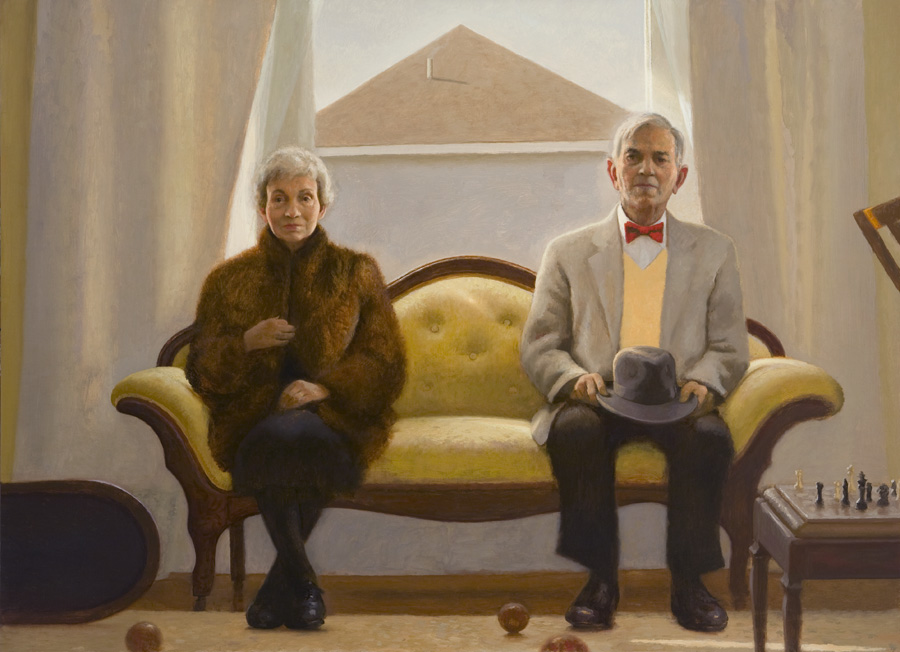

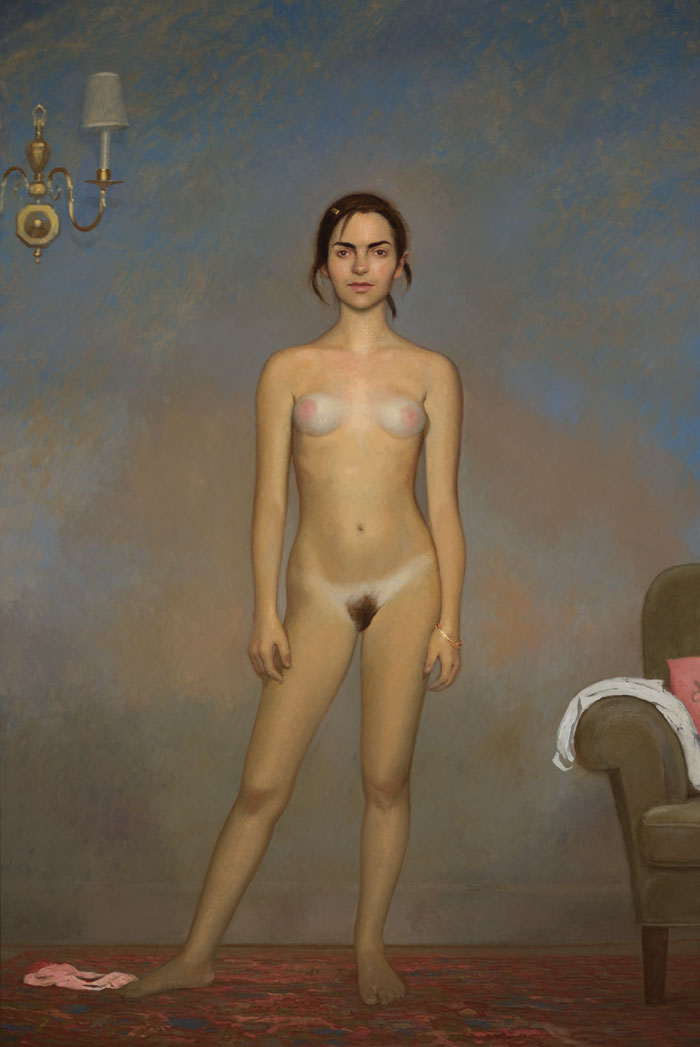

Paintings of Home

These surreal yet cozy images in Bo Bartlett’s work depict a world the painter knows best—himself, his childhood home, and family. But beyond painting what he knows, Bartlett paints what he feels, a spiritual connection between his past, present, and future lives. (Some images NSFW)

Interview by Nicole Pasulka

What does “home” mean for you and your work?

For me, sometimes in the late afternoon, at times when I’m painting and I’m really in the zone, time opens up and it doesn’t exist in a chronological way. It’s a numinous feeling where all of your life is coexisting—past, present, and future. There’s an overwhelming sense of comfort, deep meaning, and euphoria. I don’t know if it is activated just by the act of doing the work or if it is some sort of chemical-mental state where biological chemicals in the brain, plus time spent, breathing patterns, [combine to] remind me of the feeling I had as a boy of four or five or six before I’d been socialized and I’d been in the backyard and was acutely alive and didn’t have language to describe what I was experiencing. The home, what I’m trying to address, is a sense of well being, brightness, and balance, with my feet in the grass and a sense of wonder. Not a longing or aggressive urge or desire to get back into that state, but an acknowledgement, a pure or meditative state. What Buddhist monks experience as a kind of nirvana. Continue reading ↓

Bo Bartlett’s Paintings of Home is currently on show at P·P·O·W Gallery in New York through Nov. 13. He is also participating in the group show Solemn & Sublime: Contemporary American Figure Painting at Akus Gallery, Eastern Connecticut State University, Willimantic, Conn., through Dec. 2, 2010. A solo show at the Ogden Museum in New Orleans ran earlier this year. All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

And now you live in your childhood home, right?

It’s the house I dream of. Dust and skin and cells and the hair of my brother who passed and my sister and parents are there. Everything is still there [from] when I drew on the walls and scratched on the walls. It’s this giant receptacle of memory. A place where the past, present, and future collide into this moment.

All my memories are there. I’ve been slowly renovating it. My parents moved to a condo, and when I go down there for a few months at a time, I’ve restored it. Everything is still the same, because it has never belonged to anyone else.

As a child, on the edge of the forest, these woods had trails that had been there since the Indians were there. Trails through the woods, old trails where African American women would come through with baskets on their heads. One trail was a pathway to another world. At the time when they started to tear those incredible old-growth trees down, a change started to happen, and with that devastation the woods became a giant field. In the “Home” painting, I’m on all fours on the grass looking to the woods and they’ve developed that area into a whole shopping center.

It sounds like there’s some spiritual or immaterial life in this building.

Oh definitely. The thing about painting is you do capture time in a way. The time you spend, the part of the process when you’re [giving] your life over to the process, so much of the time is actually this process of looking and painting, looking and painting, looking and mixing color and painting. It sounds like it’s a technical process, but if you’re alive in the moment, what you’re experiencing is in there.

What are some of the surprises or challenges of creating work in and about the house where you grew up?

As a realist painter one of the most difficult things is subject matter; how do you decide what to paint? I don’t ever have a strategy in terms of a political agenda, or try to make a point didactically. It’s more of an experiential thing. I try to tap into what it’s like to be alive for me. Being able to paint one’s home—like, as a child, when you’re asked in first grade to do a drawing of your family or your house—it’s to take the simplest assignment and do it in the most sophisticated way you can.

It must be a pretty familiar subject to you by now.

Andrew Wyeth, my mentor, would always say, we don’t see half the time. It sounds like he’s being flippant, but it’s true we don’t hardly ever see at all. To actually see something, to spend time with it, it really becomes overwhelming. It’s the simplest thing.

Robert Irwin used to spend a lot of time in totally dark rooms so that when he emerged he’d see the world with new eyes.

I had a friend, he would look at life and imagine it was a dream. In a dream, everything has meaning. If the exercise is to walk down the street as if you’re in a dream, everything you see takes on a slow motion quality—the assignment of meaning, that’s the game were all involved in. By trying to get what it feels like to be alive into the painting and when you mix the paint.

When I’m painting, if it looks OK, the life gets in the paint, and I don’t get in the way of it. It has life in it when it gets there. It’s the whole thing, it’s not about pigment anymore, it’s a transubstantiation of the paint. It’s not in the oil, but in the emotional and metaphysical experience of one’s life in the process of seeing, mixing, and going onto the canvas. If it holds that energy throughout, where every inch of the canvas is considered, holds energy of one life, it’s a miraculous thing. When we do our work, it’s really just a record. Every artist is trying to do that. I’m of the particular mind that it’s all good. I’m extremely forgiving. I think all art is fantastic, and for me it’s a religion and I’m not a fundamentalist at all.

I think that makes people nervous sometimes.

Artists are by nature provocateurs. We need survival, and we put our blinders on. We have chosen our game and we stick to it and we get into a dualistic way of thinking and we project onto the other that ours is right and others’ are wrong. It’s not productive. It’s all good. It’s fantastic. I might be making the paintings I want to bring into the world, but it’s because I’m working from my temperament and that’s not a strategy.

So you’re work is not reactionary or provocative?

In art school, there were all these “can’t”s and I would, as a reactionary kind of thing, say, “well, let me just see if you can’t do that.” It was still a reaction to the way the teachers were engaging us to confront our art. I wanted to paint representationally for a couple reasons. It opens a window for an audience where you’re not alienating half the audience right off the bat. The hard part of being a representation painter is engaging the other half. My career for the past 20 years has been getting people to say a painting of a house is interesting.

Your paintings hardly come off as ordinary houses or domestic life.

The best thing about being able to paint your home and paint your family is you have a right to do that. Having a subject you think you own- – that’s why people do self-portraits—it’s their own.

I was very inspired by my friendship with Andrew Wyeth—he just looked and went and painted in his own backyard. It speaks to people and they’re not quite sure why. There’s something in the paint, in the good ones, and it was his willingness to put his whole being into that, and there’s a record of that, and that’s what the great paintings have: a sense of taking your breath away. There’s almost no way to quantify it. I want to paint those things that are larger than I can grasp or comprehend.

Andrew Wyeth said, “The art goes as deep as your love goes.” That has to do with that idea of wild abandon in a lot of ways. Love is about giving yourself wholeheartedly to something. It’s not just a project out of your head; it’s a project of your whole being.