Patients

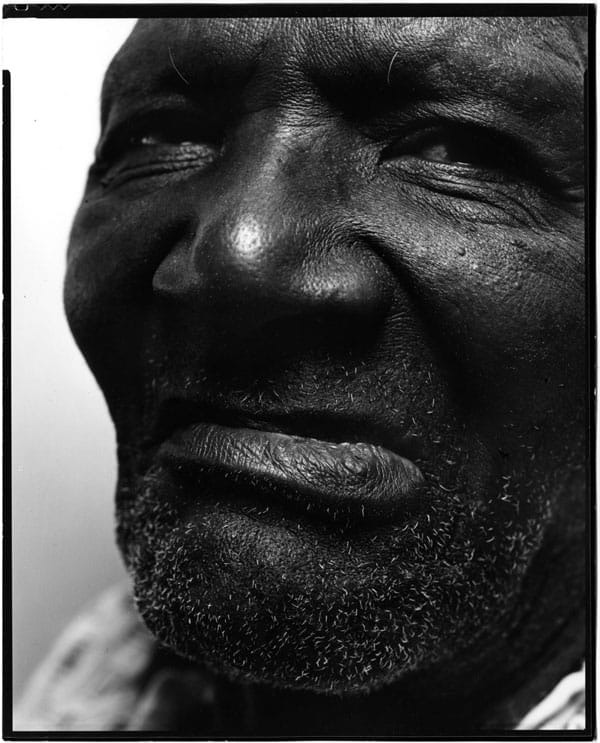

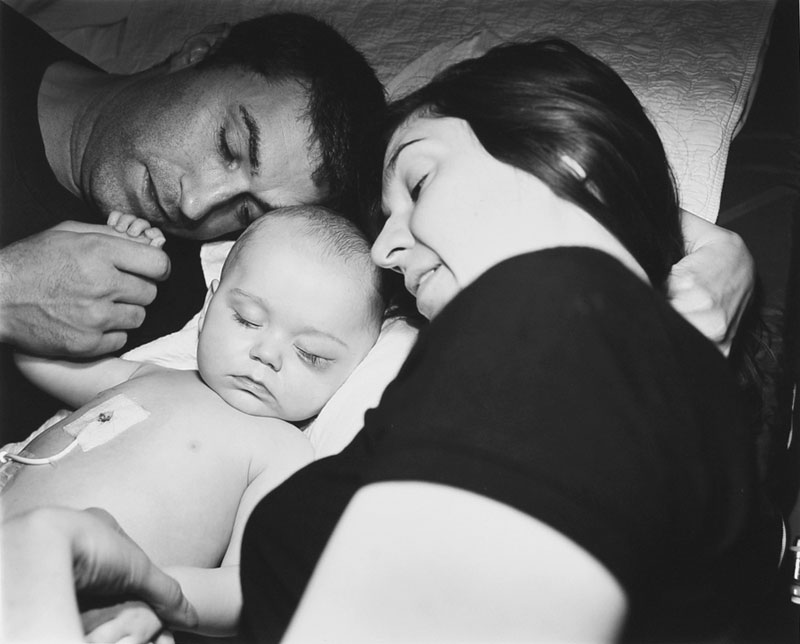

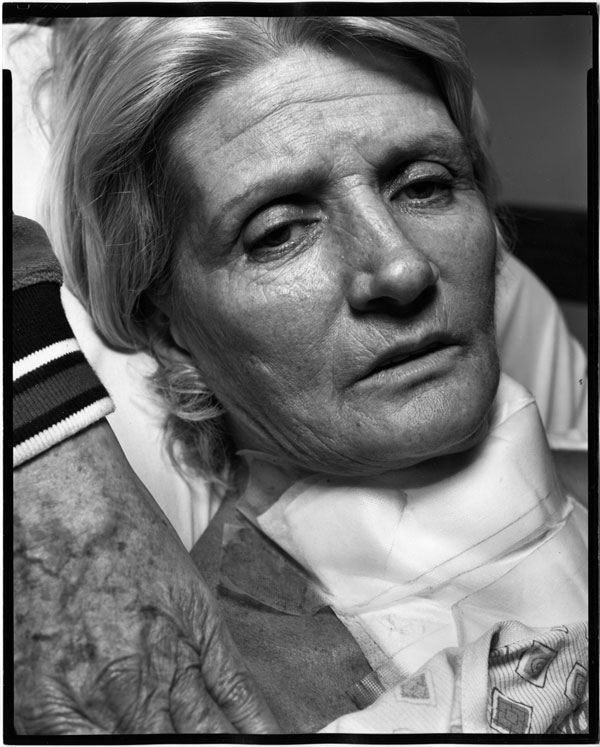

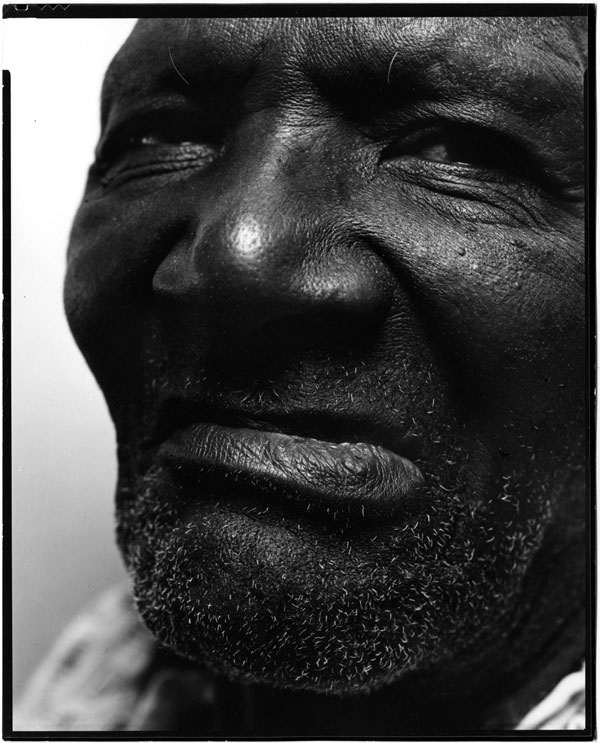

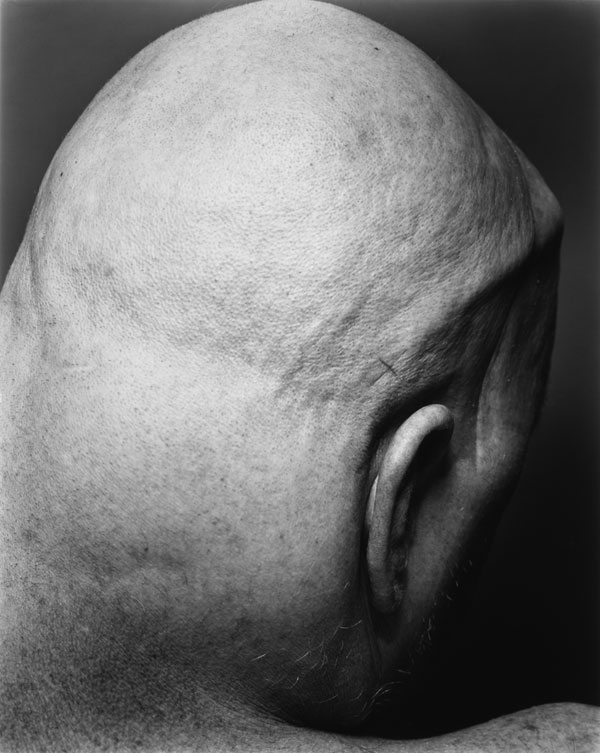

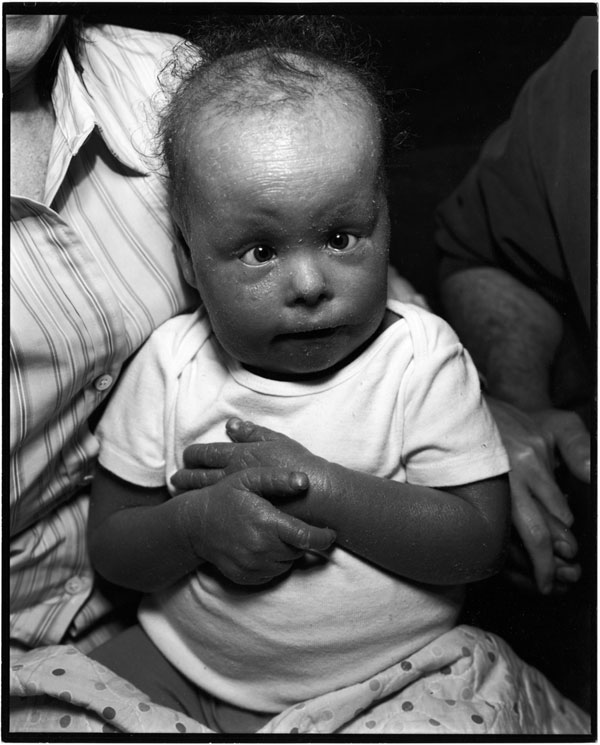

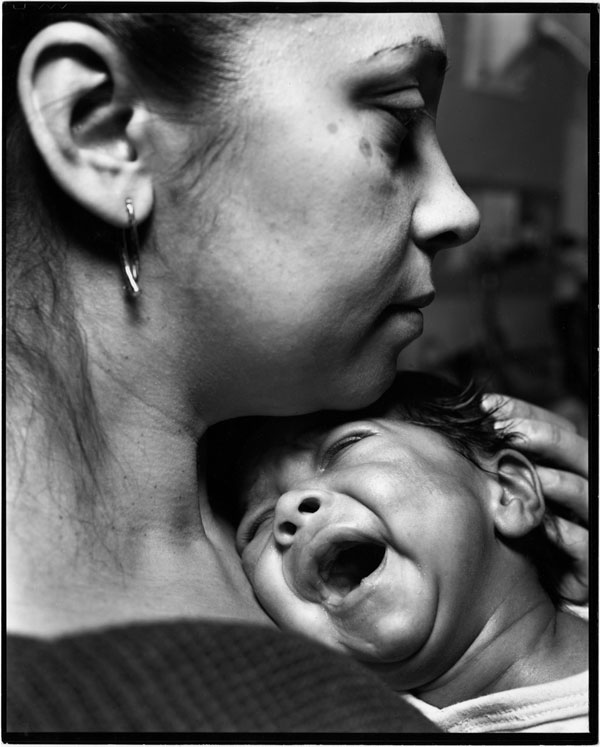

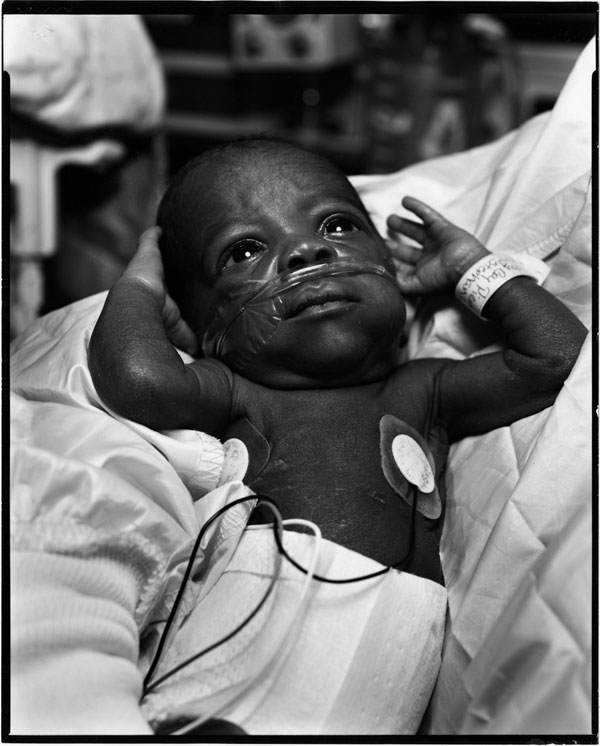

Photographer Nicholas Nixon’s portraits of the seriously or terminally ill are intimate, riveting, at times subtly shocking for their softness.

Interview by Bridget Fitzgerald

People with illnesses, particularly severe ones, aren’t often portrait subjects. What drew you to the theme?

Well, partly because of that. It’s a part of life we don’t get to see the face of very often. It’s moving, we’re all vulnerable—it’s something that’s looming over all of us. I’m sort of an old guy who’s on the side of the person who doesn’t have much power. I like the stories of the people who don’t have connections; the regular people who I think the rest of us might be better off for seeing who they are. I certainly am. Continue reading ↓

Photographer Nicholas Nixon’s new series “Patients” will be on view at Yossi Milo Gallery, New York, through Feb. 16, 2008. All images © Nicholas Nixon, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco and Yossi Milo Gallery, New York.

Interview continued

“Sarah Ferreira” is especially haunting, how she’s done her braids and the baldness underneath. How did the series come about?

My father-in-law had cognitive heart failure and Alzheimer’s. As he died he got both sweeter and more diminished; I took care of him a lot. I took a few pictures of him and my wife—I was surprised, I just took them, not for art, and I liked them a lot. The way he was there and not there.

The first institution was Dana-Farber, the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, and I found the head of palliative care; she was a shrink and she liked the idea. She told others. Some other docs asked their patients if they wanted to participate and if they said yes, I called them up.

Some of these pictures are extremely private, and privacy’s a difficult thing to preserve when you have an illness or are in a hospital. Did this make your job easier, finding those private moments?

I always felt kind of bad, because until they got to know me and I got to know them, I felt like just another person intruding. I felt kind of guilty. I wanted them to tell me that it was OK, before I got into my regular artist gear, my artist mode. And it turns out that most of the people, once they agreed to do it, or decided they want the picture, or think it’s going to be something of value—once they’ve made that decision, it’s not an intrusion at all; they like me there. That’s sort of the satisfying part for me. I feel like I’m not just taking from them.

Did you acquaint yourself with the medical situations or conditions your subjects were experiencing, or take everything at face value?

Pretty much, but not all the science. The girl you mentioned, Sarah Ferreira, she had cystic fibrosis. She and her doctor told me about it, I didn’t know what it was. She had had a lung transplant and was maybe going to get a second lung. But it’s also political because then I go over to Boston Medical Center, and they say cystic fibrosis gets too much attention because it’s white, and people give too much to the white disease over things like sickle cell, which is mostly black people. Cystic fibrosis is—you become a shrunken version—but with sickle cell, it’s constant pain. With something like sickle cell there’s more drama on the inside than there is on the outside.

Hospitals don’t always feel like places where people recover. What was your impression after all your time?

I know the science—I know that people do get well, in the larger sense, but I’m also very sympathetic to how people feel. A lot of people are angry and mistrustful of the care they’re getting. Especially when its economical—on the lower end, there’s a lot more mistrust because there’s long waits and doctors aren’t as nice to the patients. On the more luxurious end, there’s more attention. That’s why I like working on the lower end—the city hospitals.

I was in the hospital a couple of months ago for surgery, and part of me can’t imagine having my photo taken right after, while another part of me would have been really interested to see the objective view. Did any of your subjects see their portraits? What were their reactions like?

Most of them liked the pictures. They know what they look like; they’re not surprised by it. I was expecting them to say, “oh I look so awful, get out of here!” Instead they said, “oh that’s a nice one, oh that’s a sad one.” The form of the photograph is different than what they’re used to looking at. It’s black and white, and very sharp. A lot of times I let them look through the camera to get a connection. The ones who write me cards, or send me notes—the people I hear about seem to be gratified. There’s an acceptance.

It’s hard to explain. If you told me in the beginning that it was part of my job to take a photograph that they would like, I wouldn’t enjoy it, but I find that I do that anyway. I don’t want someone to tell me that I have to do that, but… I pretty much make sure that there’s something they like in the envelopes. If I take six exposures, they get six prints.

How did the subjects, or their loved ones, react to the portrait process?

On the whole, very positively. The camera is a wooden box on a tripod. It’s real unusual. So the people who are old, it reminds them of something they knew, and the young people, it’s real unusual for them. The camera is friendly. When I walk away, people seem to have a good experience. That’s what makes it fun for me: on the one hand, getting the picture I want, and on the other, having them like the experience—participate in and enjoy the experience. I don’t want them to feel like I’ve taken anything they don’t want to give me. I’m a little bit like a Don Juan of the camera. We need to dance around the floor a little before we know if we’re going to kiss or not.

What are you working on next?

I am continuing to work at Boston Medical Center, but the pictures are less about serious illness and more about what happens there—successful breast cancer treatment, successful twins being born. Successful radiation treatment. You know, women get breast cancer now and it’s so much more treatable. I spend a lot of time in the ER and almost everyone gets healed—it’s like a patch up place. I like the feeling of that.

The project has changed from being serious illness and palliative care to what really happens at this hospital. I’m not a big thinker. Usually a project is over when I get bored, when the picture is too easy to take. When I was 25, there wasn’t really any possibly of making a living at being a photographer—except Ansel Adams. I feel so lucky to be able to do something I love every day, so I feel like I better do a good job at it.