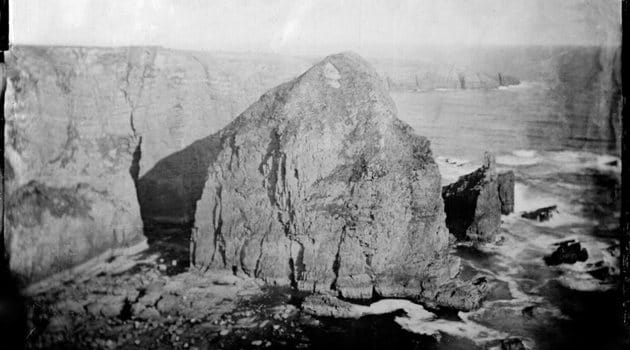

Point of Deliverance

Pictures from the edges of the Northern Gaeltacht, the Irish-speaking area of County Mayo and one of the last true wilderness areas in Western Europe.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

The Morning News: Where did the name “Point of the Deliverance” come from?

Alex Boyd: It’s the translation of a Gaelic name of a prominent rock which sits in the natural harbor of Portacloy, in the remote northwest of Ireland. The name, which is at least many centuries old, was given by local fishermen who knew that if they passed that point during stormy weather they would make it back home to safety. It is a name which perfectly encapsulates the struggle between the sea and those who live on that unforgiving coastline. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, copyright © the artist, all rights reserved.

,_1m_x_0.75_.jpg)

Interview continued

TMN: In your project statement, you call the Gaeltacht one of the “last true wilderness areas in Western Europe.” What are others?

AB: The wilds of Rannoch Moor in the Scottish Highlands, a vast empty moorland, and the last place that wolves were seen in Scotland. I can see another, the Knoydart Peninsula, from my studio window on the Isle of Skye. It’s incredibly remote, only really accessible by boat, and is surrounded by a ring of formidable mountains.

TMN: Have you completed the series yet?

AB: Not yet—I’ll be returning to the west coast of Ireland again later in the year to work on it further. It’s part of a much larger project to document the edges of the Gaelic speaking world. Eventually I’d love to travel across the Atlantic and work in places such as Nova Scotia, but time will tell.

TMN: Which comes first, the subject or the shot?

AB: For me it’s always been about the subject. I’m not the kind of photographer who takes thousands of images. I work slowly and methodically on one or two images. Most of the work takes place in planning and pre-visualising the image, and sometimes not taking a shot is part of that process.

TMN: What’s your favorite camera at the moment?

AB: I recently swapped a print for a very rare Black Leica III from the early 1930s. It’s the camera I always wanted as a kid, as it was the choice camera of a favorite photographer, Werner Kissling.

I’m also very fond of my large Victorian plate camera called “Karl” which I use for the wet-plate collodion process. It’s the main camera I used on the “Point of the Deliverance” series and has accompanied me on my travels for several years now.

TMN: When was the last time you were confused by a piece of art?

AB: This morning I was looking at the work of Joan Mitchell and Robert Motherwell. I keep returning to American abstract painters recently. I enjoy work which slowly reveals aspects of itself over several viewings.

TMN: Your “Sonnets” project has garnered a lot of attention. Could you recreate it somewhere else other than Scotland?

AB: “Sonnets” is tied closely to the work of poet Edwin Morgan and the Scottish landscape, so it can’t really be done anywhere else. This, however, hasn’t stopped fans of the series making their own “Sonnets” shots, and I’ve had people send me images from The Grand Canyon, New Zealand, and all over the world.

I do, however, plan to create new staged landscapes across Northern Europe, and explore some of the themes in Sonnets further, beginning in Iceland next year.

TMN: Susan Sontag said, “To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them that they can never have.”

AB: While I agree with elements of Sontag’s statement, I feel that a complete knowledge of ourselves and the way that we are perceived will always elude us, as gaze is entirely subjective. Does the photograph reveal more as a document? Does this make the presumption that photographs always tell important truths about their subjects? I find that problematic. It must also be said that, to paraphrase Avedon, every time a photographer makes a portrait, they too must reveal something about themselves. I feel that this has always made for the strongest portraiture.

TMN: Coffee or tea?

AB: I’m what Scots call a Tea-Jenny—I can’t function without several cups of Earl Grey a day.