Polaroids

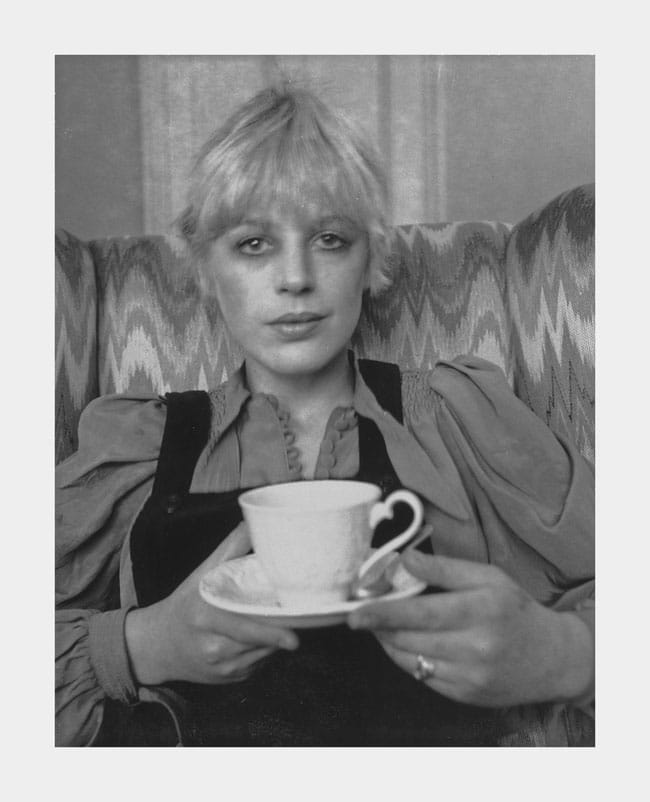

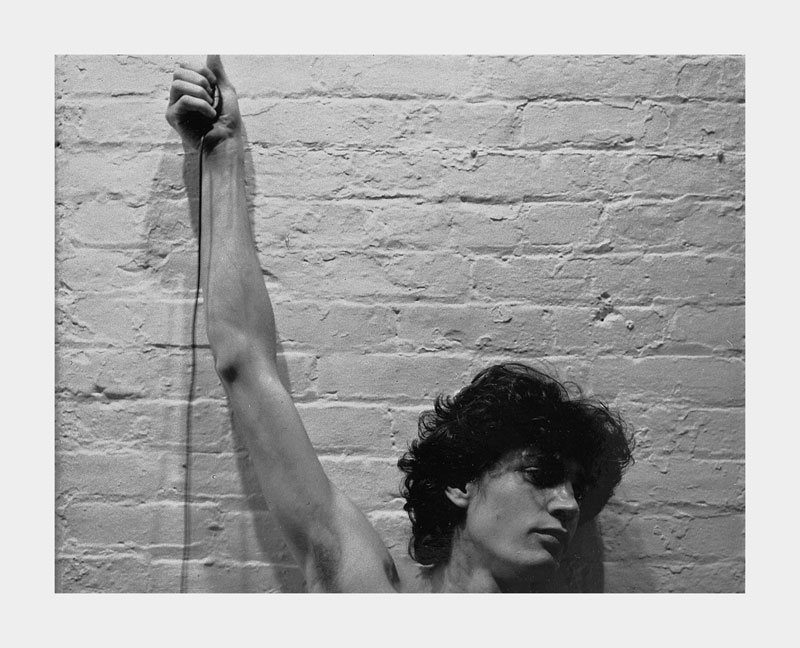

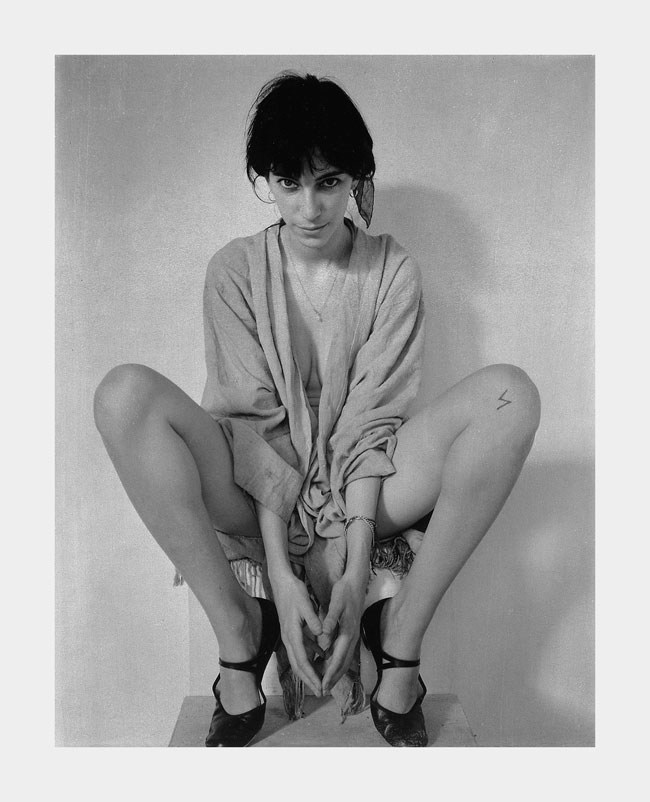

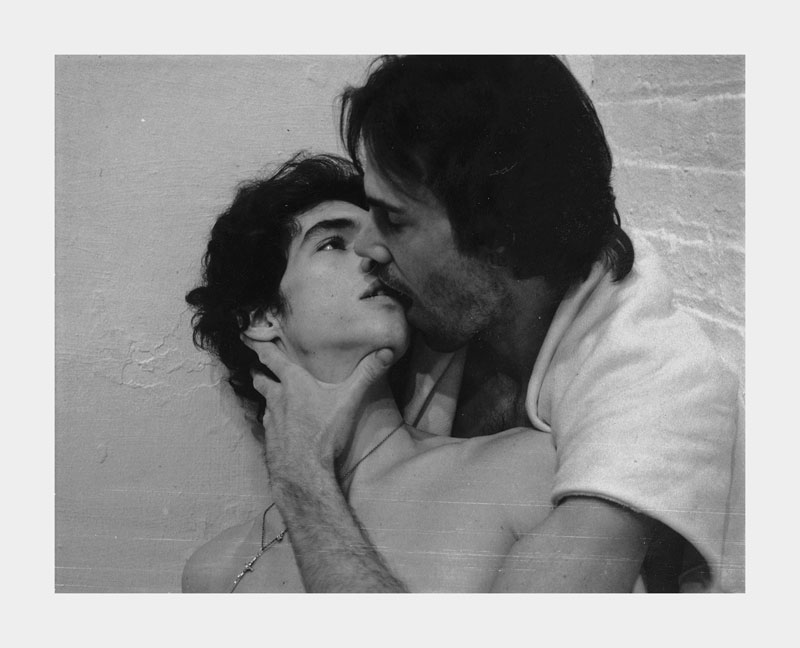

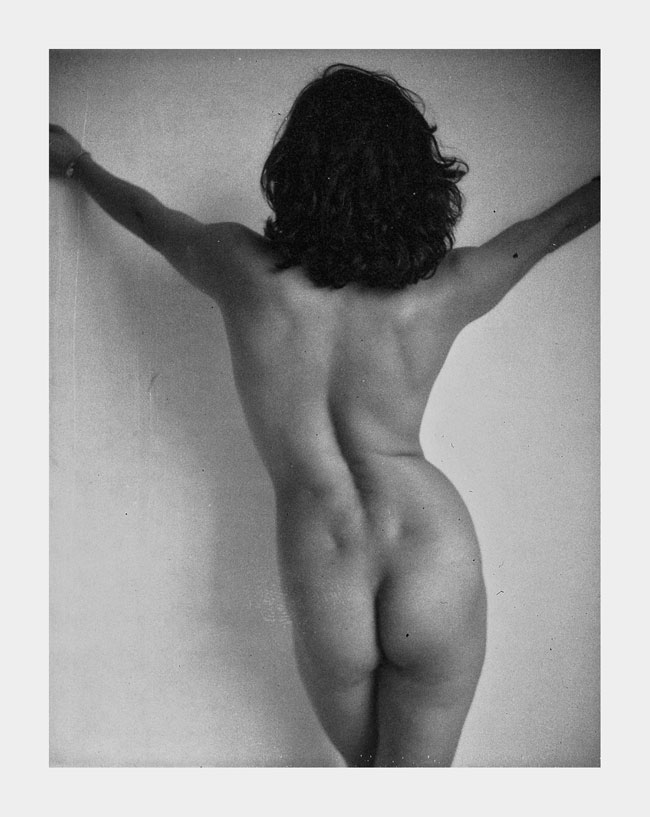

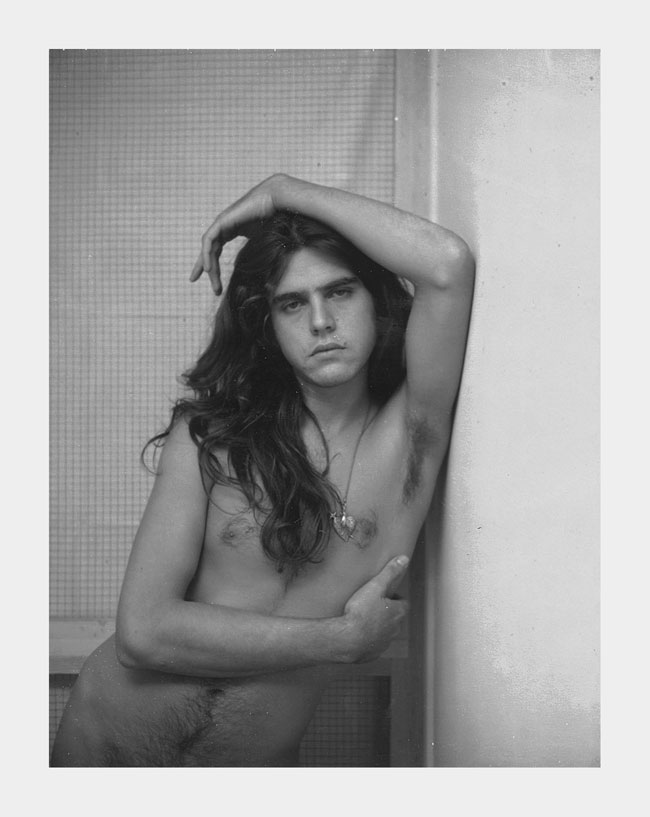

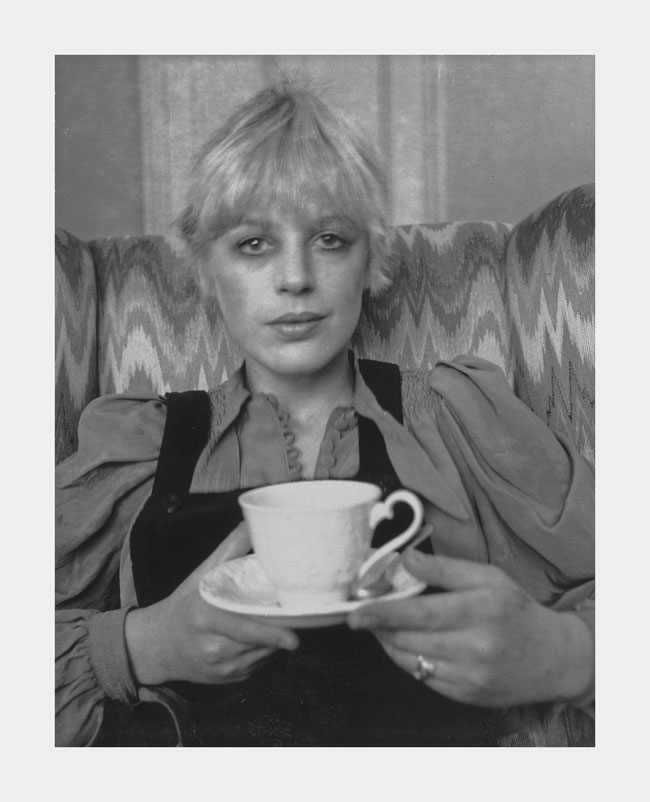

For photographers, the Polaroid was toy and tool, means and end, and Mapplethorpe handled it magnificently: roughly with sex, playfully with himself, carefully with faces, studiously on the body.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

Polaroid recently announced that it will stop producing film for instant cameras, now that the world’s gone digital. What are we losing? For photographers, the Polaroid was toy and tool, means and end, and Mapplethorpe handled it magnificently: roughly with sex, playfully with himself, carefully with faces, studiously on the body.

Sylvia Wolf’s new book, Mapplethorpe: Polaroids pulls together about 300 images, many never before published. Wolf is adjunct curator at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. She is the author of numerous critical works on photography, including Ed Ruscha and Photography, Julia Margaret Cameron’s Women, and Michal Rovner: The Space Between.

Read our interview with Sylvia Wolf ↓

All images used with permission, courtesy Prestel Publishing, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview

Polaroids always look amateur to me: fast and cheap and wonderful. What drew Mapplethorpe to the format?

A camera that produces an instant photograph allows both photographer and model to respond to the image as part of their interaction. Indeed that was the primary appeal of the Polaroid process for Mapplethorpe: it was immediate. Long before digital technology made instant-viewing a standard part of picture-making, Polaroid cameras gave rapid results. That was part of its appeal for Mapplethorpe. Seeing in the moment allowed for a free access to feeling and thinking.

You say Mapplethorpe’s pictures appeal both to “the rough and the refined.”

Not all Mapplethorpe’s pictures, but the Polaroids in particular. There are tender images (flowers placed on a pillow, for example, plate 25) and tough images (weighted scrotum, plate 135). When the work is seen as a whole, we see Mapplethorpe using the Polaroid camera as a companion and witness to the full range of his experiences.

Polaroid recently announced that it will no longer support the instant format. What are we losing?

We will lose the ability to make instantaneous photographic prints. But digital technology has taken over the world of immediate image making.

How much attention did Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids receive while he was alive?

Very little. The Robert Mapplethorpe archives give evidence of only one solo show, at Light Gallery New York in 1973, that featured Mapplethorpe’s Polaroids. No exhibition records remain to tell us which ones were on view.

Were the sexually explicit pictures meant to shock?

When asked whether he made sexually explicit pictures to shock, Mapplethorpe replied that his first priority was to satisfy his own curiosity. He has said that he was surprised that others found his pictures shocking. Once he had taken a photograph, it wasn’t shocking to him: He had been through the experience.