Puzzle Over and Over

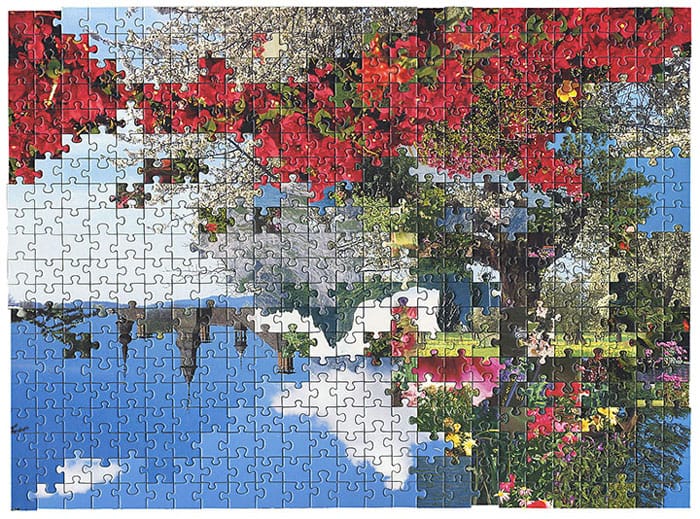

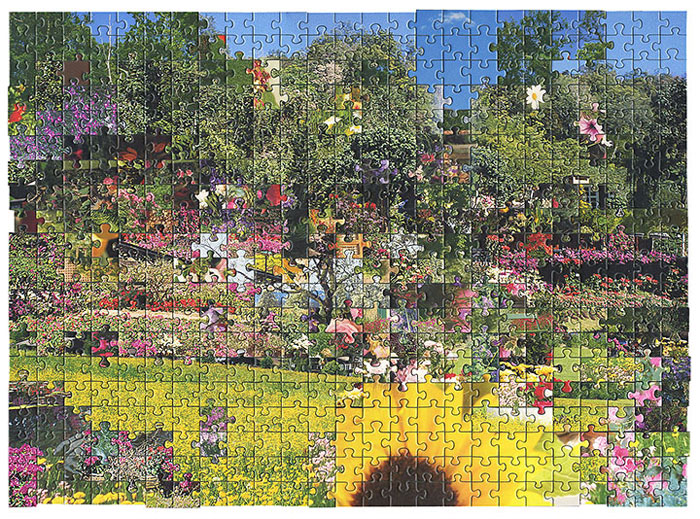

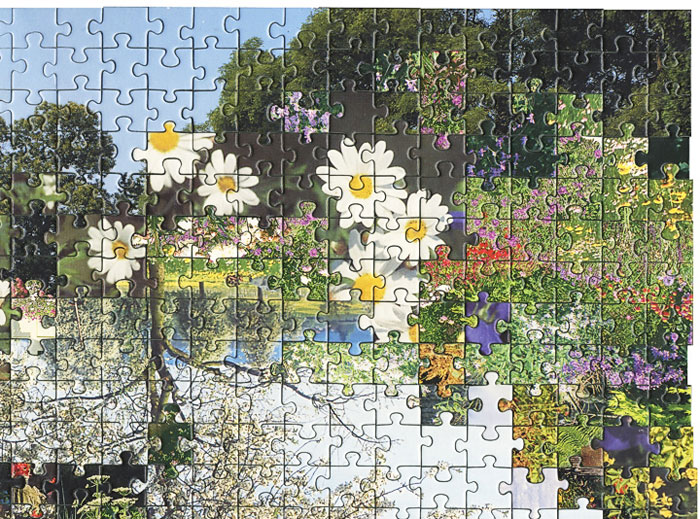

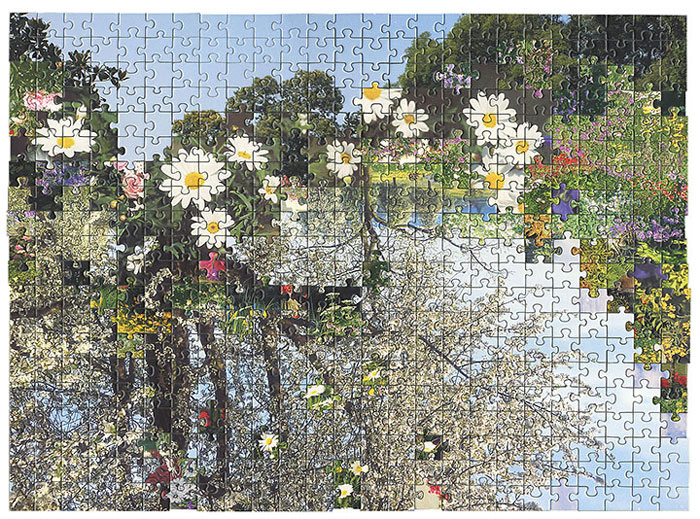

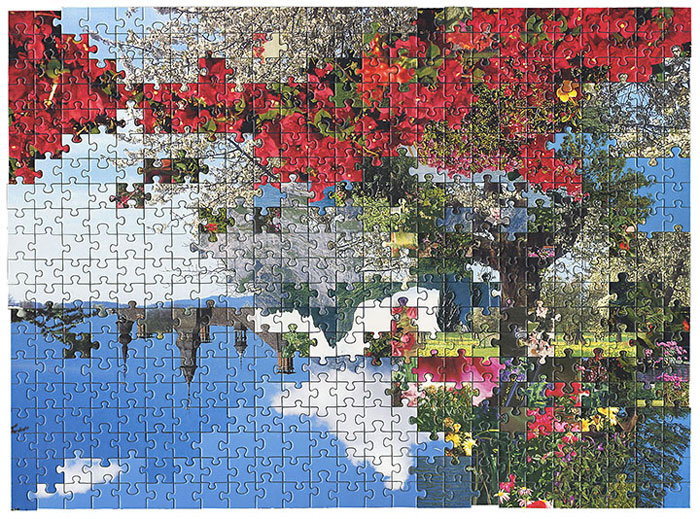

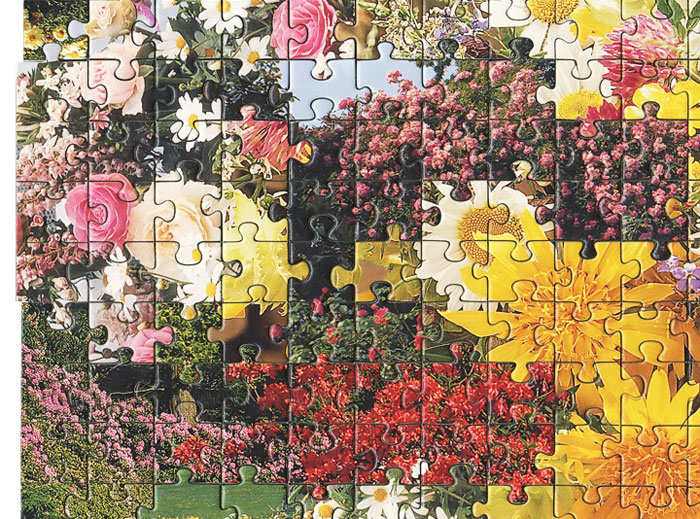

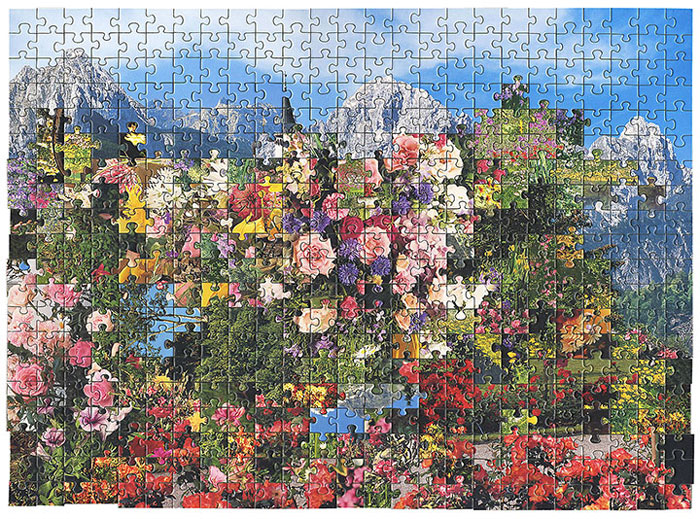

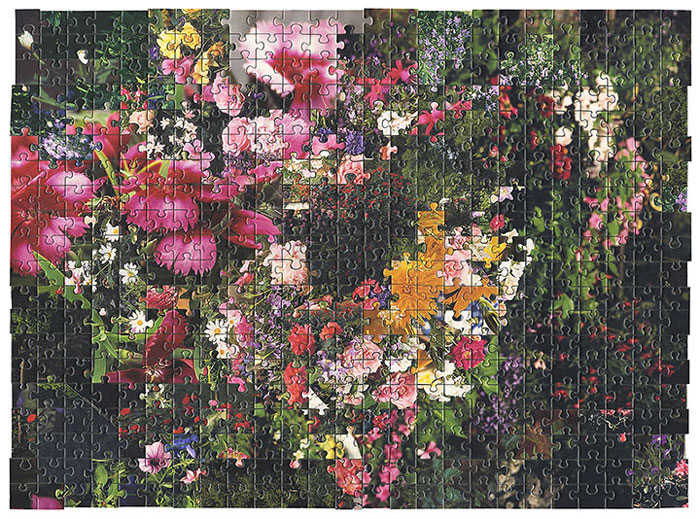

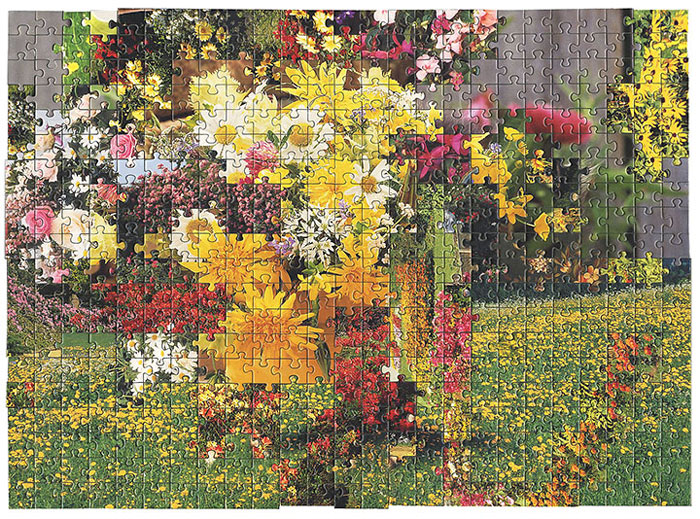

Kent Rogowski's “Love = Love” project delivers pure wonder at these puzzles remixed to make new scenes, abstract floral artwork where once there were cats.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

Kent Rogowski’s “Bears” was love at first sight. Recently we saw his “Love = Love” project, and the feeling was pretty much the same: pure wonder at these puzzles remixed to make new scenes, abstract floral artwork where once there were cats. As Kent notes below:

I was riding on a train and for some reason the thought popped into my head that a puzzle manufacturer would probably use the same die to cut all of their puzzles that shared a piece count in order to decrease manufacturing costs. We think of a puzzle piece as something unique and individual that has a specific place. The thought that it might fit somewhere else and form something new and unexpected interested me.

All images courtesy Kent Rogowski, all images copyright © Kent Rogowski, all rights reserved.

Artist interview

First, tell us, and no lies: how long did it take you to put these puzzles together? I find puzzles incredibly boring, but I love the idea that you could make whatever you want—sort of liberating.

Well, the project was so time consuming I only felt liberated at the end when I ran out of puzzle pieces. When I started, it took me a day or two to put together a 500-piece puzzle. After spending about a week slowly putting puzzles together I found a way to quickly assemble them that most puzzle enthusiasts would probably consider cheating. I was then able to finish a puzzle in a few hours. After putting around 40 puzzles together I actually got to the point where I could recognize certain pieces and knew exactly where they went in the puzzle.

So assembling the original puzzles was tedious but that was only the beginning. Once I had taken large parts and individual pieces out all the puzzles it got very difficult to keep track of the 20,000 puzzle pieces constantly moving around my studio. Most of my time was spent searching for specific pieces to fill holes in the puzzles. It was kind of a ridiculous process. If I had started the project in a more organized way it probably would have saved me a lot of time. Instead my studio quickly became very chaotic with puzzle pieces covering any available flat surface.

Where did the project begin? And how did you know that a single company’s puzzle pieces could be fitted together?

I was riding on a train and for some reason the thought popped into my head that a puzzle manufacturer would probably use the same die to cut all of their puzzles that shared a piece count in order to decrease manufacturing costs. We think of a puzzle piece as something unique and individual that has a specific place. The thought that it might fit somewhere else and form something new and unexpected interested me.

At the time, I had also been thinking a lot about relationships and how two very different people can come together and their differences will often compliment one another. The thought of two different images coming together seemed to relate to that at least tangentially. It isn’t important to me if a viewer got that association but that was the original motivation for the project.

What were some of the original scenes the puzzles were supposed to show?

Most of the scenes were either bucolic images of country houses and castles or of cats in various settings. Overall the original images were pretty cliché and bland and exactly what you would expect to see in a puzzle. I decided to select the flowers and skies because they were secondary elements in most of the images and they contributed to the romanticism that was part of the original images.

When I was putting the montages together, it was actually hard to fill in certain areas of the puzzles because of the compositions of the original images were very similar. I would usually have a hole about a third of the way into the puzzle where either the cat’s head or a castle had been. In the end I think this problem helped the project because I had to find creative ways to fill those spaces.

Considering “Bears,” where does this interest come to reconstruct, to remake?

I have always liked taking things apart and figuring out how they were made and this naturally transitioned into my artwork. I think interesting things can happen when you transform something that is mass-produced into something unique and individual. While there is an implicit critique of consumer culture in my work, I am more interested in what happens when you use the products that surround us on a daily basis as a vehicle for self-expression.

Another thought about “Bears”: When you were turning the bears inside-out, the results were often positioned and portrayed to express personalities—sort of the animal within the bear. Was this project more abstract? Did you have a good idea of how you wanted the newly completed puzzles to turn out?

This project was much more abstract. Once I figured out what I was going to do with the inside-out bears, it was just a matter of collecting enough teddy bears that were different to make the project work. With “Love=Love” the process was much more fluid and creative. My original idea was completely different than what you see in the final pieces. After I had worked with the puzzles for a few days I quickly realized that my original plan was not going to be interesting in any way. That is when I started to look a little bit more at the imagery that was used in the puzzles and found a new direction for the project. Each puzzle had a different set of challenges which forced the project to evolve and also kept the process engaging.

What’s up next?

I have been collecting used self-help books and am interested in how their former owners interacted with them. You can see in the person’s notes and marks how they thought the books applied to them—sometimes even changing the text of the original to make the advice applicable to their situation. However, I am not exactly sure what the final direction of the project will be since it is very much in process.