Quiet As Kept

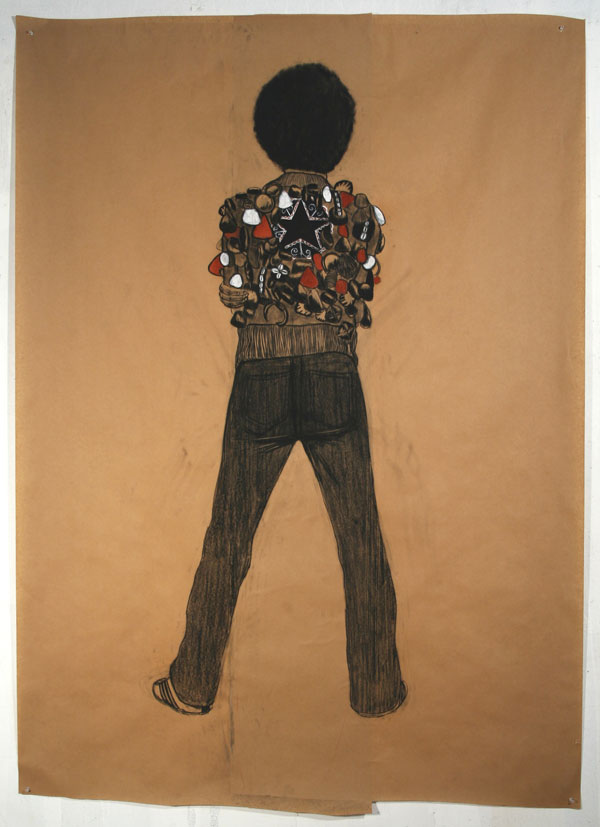

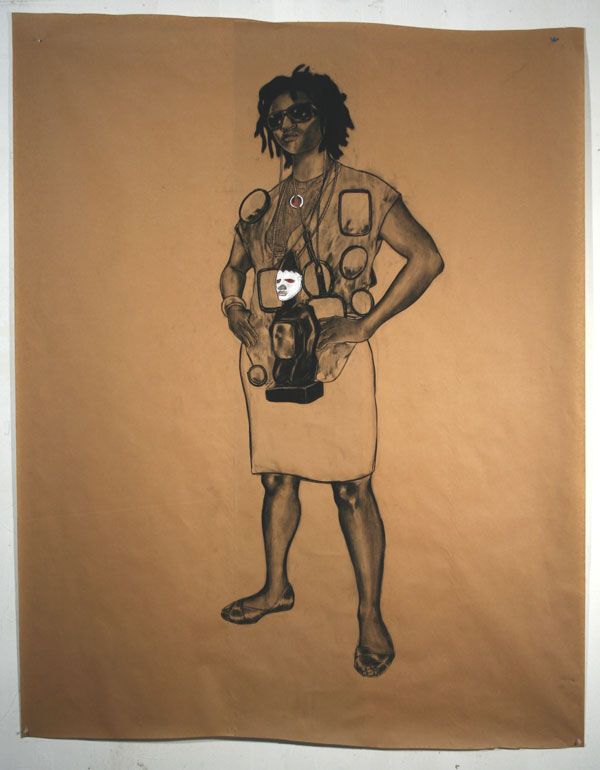

Robert Pruitt’s butcher-paper drawings give us complex characters, full of personality but limited in how much they share. It’s art as tease, pose, and challenge. Refreshingly, it’s also very engaging.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

Tell me about where this show came from. How long have the works been in development? Who are these people?

These people are my people: friends, co-workers, ride-or-die cohorts, etc. I have been thinking about the show and the drawings for about a year, but only in bits and pieces. The images and ideas didn’t really start to cement until about three or four months before the opening.

I had become a little frustrated with my drawings and I stopped making them for a while. I wanted to push myself a little further and I had a difficult time figuring out what that meant. I knew I was dissatisfied but I didn’t know why. I realized that the dissatisfaction was in part because of how artwork operates. What I mean is that I work a lot with issues that become contradictory when I place them on a gallery or museum wall. I am trying to resolve that but I still wanted to make really interesting figure drawings of black people. Continue reading ↓

All images appear courtesy of the Clementine Gallery, where Quiet As Kept is on view through Jan. 6, 2007. All images are copyright © Robert Pruitt; all rights reserved.

Interview continued

The subjects in the butcher paper pieces are defiant, powerful, and very stylish, but they’re also masked and hidden, whether behind sunglasses, headdresses, or blankets. Are we talking pride or shame?

That’s a perfect question. I am dealing with both here. There has always been shame (needless shame) associated with black folks. When it comes to our bodies, our speech, our neighborhoods, whatever, when it is black it is less. Mind you, this comes from outside of us, but we start to internalize this shame, especially in the public sphere. And we have no hiding place from this public sphere. I am making a visual representation of a space where we could separate how the world sees us and how we see ourselves. In masking themselves, each figure has created a protective device that allows them to see and not be seen.

In your process, do you begin with concept or with feeling? Are you working with an argument or something less defined?

It’s a mixture. I start with an undefined image in my head, but I don’t think I could (or should) explain that. There is always a feeling. I am trying to create freshness.

You wrote:

It seems that one of the most damaging aspects of living the black experience is the constant blast of inside information being broadcast to the world…Dances are stolen, neighborhoods gentrified, language appropriated, and images exploited…The risks of constantly giving away cultural productions and idioms is that it leaves your community naked.

This sounds like what Dave Chappelle went through recently—feeling like he was exposing secrets of the black community to a primarily white audience. Do you have any similar feeling about putting your art up on the wall?

Yes. That is what I was getting at earlier. My work is concerned with blackness being misperceived out in the world, but here I am making images of black bodies to be consumed out in the world. That is the contradiction I mentioned. However we have always been forced to lead this contradictory existence. I think Dave Chappelle is the perfect example. Nobody misses that show more than me, but man, I completely understand the predicament. We as black folks understand that most of those characters were exaggerations of black people and their experiences and we could laugh at ourselves—I even think that there is healing in that laughter. However, that show was broadcast to the whole world and there was no filter to explain some of that stuff and it ended up coming off a little too close to minstrelsy. It wasn’t at all, but without the context of a lived black experience it looked dangerously so. There is no sacred secret space for my community, and that is what we need—a place where we can discuss Ashy Larry in private.

In my drawings I have made my characters unavailable to the viewer. There are still plenty of things to look at but you will never know these people through my drawings. There is not enough—or the right kind of—info to box these people into easy categories.

I love “Shining Black Prince Medina”—the contrast of the chair and the man, and the trousers, sneakers, and coat working with the mask and headdress. He’s out of this world, but in this portrait he’s very much his own man. Do you see your figures blending eras or regions?

Yes again. I like to collapse the myriad examples of black experiences into one person. I believe this creates a 3D quality that is typically denied to our existence. Because of racism we are always put into some box. Whether you are a ball player or rapper are any other trope of blackness, you can still be other things all at the same time. An African, a Black Panther, a writer, a scientist, or whatever, and you still look fresh while doing it. Medina looks complex because he is complex and he is comfortable with being all that he is.

But is that kind of mixing you depict something people can really accomplish, or do you show fantasy? Aren’t we always locked to our own place and time?

I may render theses images in a wild fashion, but in some sense these people have already accomplished this mixing. The problem is being perceived that way. One of my favorite influences is Sun Ra, and I don’t think he was locked in his place and time. He could have easily been one of my drawings.

What are you working on now?

I am preparing for a residency at Artpace in San Antonio. I’m not sure exactly what I’ll make, but I’m interested in pushing some of the ideas in the Clementine show even further.