Reconciliation

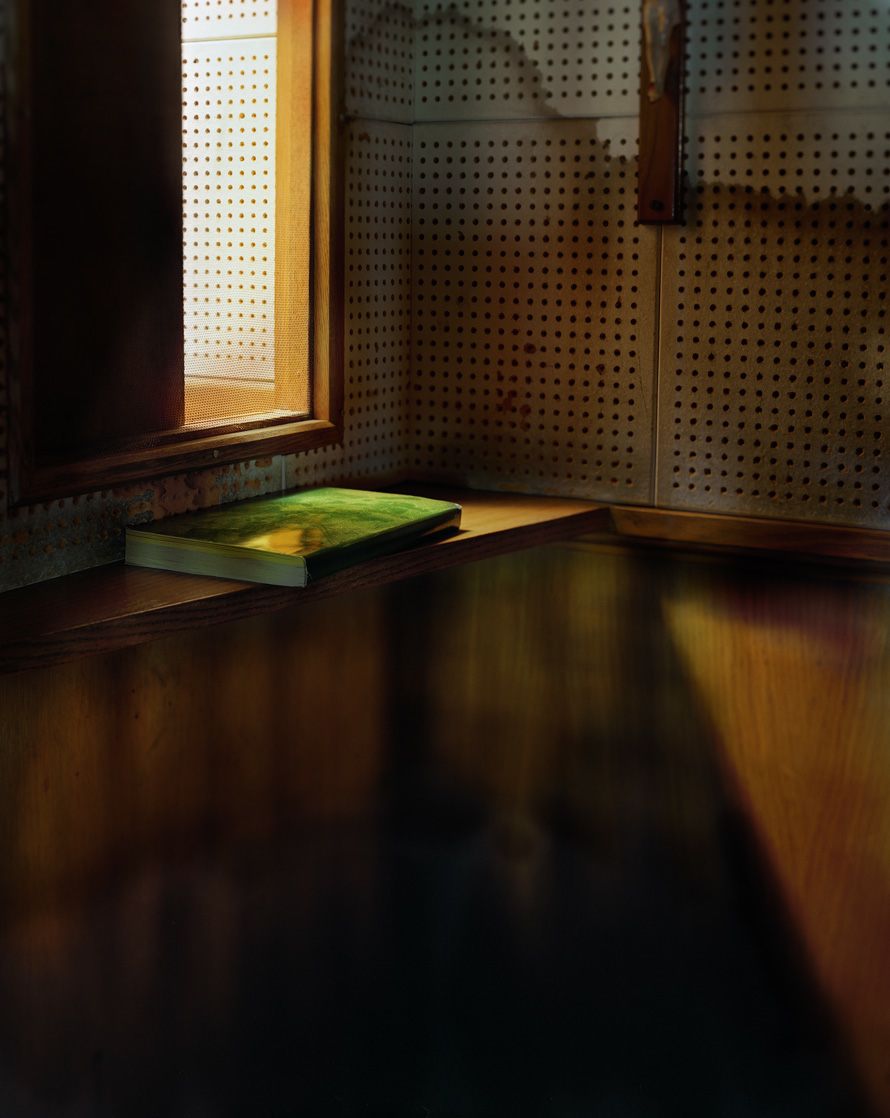

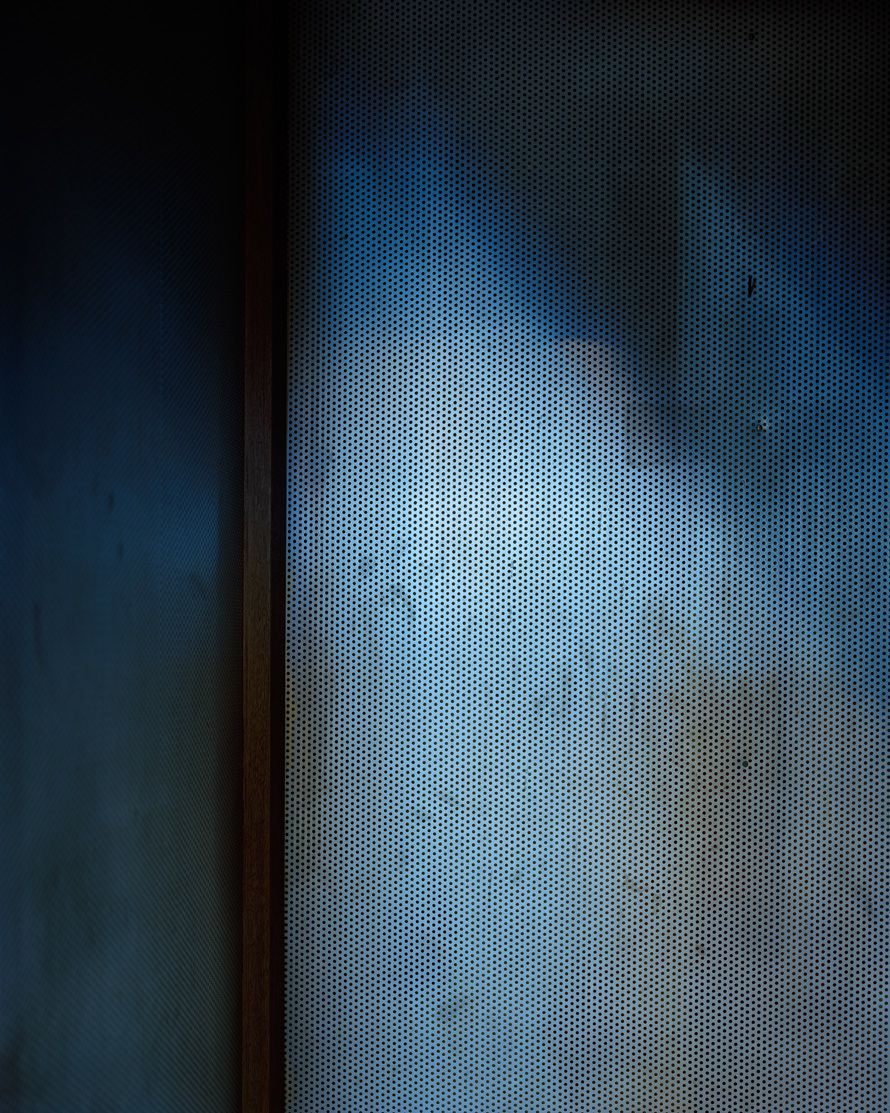

Confessionals are designed to draw the penitent into soul-searching. The spaces themselves are bare, but our knowledge of their function can make viewing more complicated.

Interview by Rosecrans Baldwin

TMN: When did Catholic confessionals begin to call to you? What is the source of your inspiration?

Billie Mandle: The project began while I was in graduate school. I had been thinking about the idea of forgiveness—what does it mean to forgive? How do people actually forgive each other? Confessionals were in the back of my mind as I was raised Catholic. I have always been fascinated by the way confessionals become containers—holding people’s voices and secrets. While researching confessionals, one of the things I found interesting was that the confessional is meant to point away from itself, to be invisible. The small rooms should draw the penitent into introspection, which is why most confessionals are completely dark. When the project started I liked the idea of trying to photograph spaces that are meant to be ignored. Continue reading ↓

All images used with permission, © copyright the artist, all rights reserved.

Interview continued

TMN: The photos’ captions name the churches, but not the place. Where are they from?

BM: The photographs are from all over the United States. Initially I included the cities in the titles, but felt that the photographs became too much about the specific church and city. People read the confessionals as representative of that city.

TMN: In your statement for the series, you say “I am interested in the way the ordinary materials of walls and kneelers are transformed by each confession.” How were they transformed?

BM: Most confessionals are small rooms, made from sound tile and wood. But knowing the function of the rooms changes them—not necessarily visually (although the kneelers are often indented and the walls scuffed) but in the way we think or feel in response to the spaces. These are rooms where people confess their sins and ask for forgiveness surrounded by the traces of other people’s confessions; I like the way this idea influences the experience of the spaces.

TMN: Why not shoot the other side of the confessional, where the priest listens?

BM: I made many photographs from the priest’s side but ultimately decided not to include them. The images felt out of place and seemed to address a different set of questions—they were about granting rather than seeking forgiveness.

TMN: You’ve shown us how these rooms can be quite beautiful when they’re empty. What do you see first, the confessional’s architecture or the people who have used it?

BM: It depends on the spaces. In older confessionals I see the people first. In some of the newer churches I see the architecture. The two go hand in hand so I think the pictures are more successful when I am able to see both clearly.

TMN: What are you working on now?

BM: I have been working on a couple of different projects—photographing archives and parking garages—thinking about the way architecture acts as a container for people’s experience.